A new exhibition entitled Jewellery – made by, worn by / SIERADEN – makers & dragers opening at Museum Volkenkunde on 13 December will be an ode to jewellery makers all over the world. Crafts and techniques that date back centuries, such as gold and silversmithing, tell tales of culture, history and identity. The exhibition will feature the most beautiful items of jewellery from the collections of the Museum Volkenkunde, the Africa Museum, Wereldmuseum Rotterdam and the Tropenmuseum. These include delicate gold pieces made in Asia and South America, items made from a huge range of natural materials from Oceania, silver jewellery with special meanings from North America and the Middle East, as well as beadwork from Africa.

The exhibition will profile jewellery makers from all around the world, from traditional gold and silversmiths to contemporary designers. While for some makers their choice of material and technique is a way to preserve local traditional skills, for others it is a way of rejecting them. Some makers reflect on their own culture while others combine elements from different cultures and use previously unknown techniques. But personal fascination or the latest fashion can also define the look of a piece. The jewellery in the exhibition is made not only of precious metals and stones, but also materials like beads, wood and plastic, and the use of new techniques melds tradition and innovation. Featuring over 1000 items of jewellery, the exhibition will be an ode to the craftsmanship, passion and dedication with which jewellery is made throughout the world.

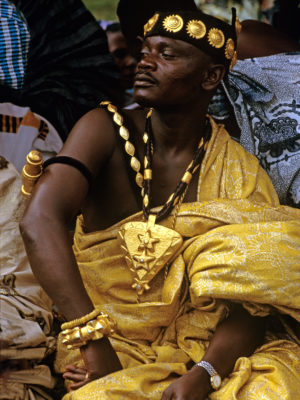

Asante goldsmiths

Before the discovery of America, most gold came from West Africa. The Asante kingdom was the most important supplier of gold to Europe. The kingdom, which still exists, flourished in the 18th century, covering an area that corresponds roughly to present-day Ghana. Not surprisingly, this abundant supply of gold led to some very high-quality goldsmithing. The Asante were known for the quality and skill of their goldsmiths. Those who worked exclusively for the Asante king included specialist craftsmen from areas conquered by the Asante. These specialists lived at the court and they passed on their skills to local goldsmiths. Only high-ranking individuals and members of the royal family were allowed to wear gold jewellery, and therefore goldsmiths were held in high esteem. At the same time, the skills of goldsmiths helped to enhance the status of the king. The craft would be passed from father to son. Today, knowledge of gold working is increasingly passed on through an apprenticeship system, whereby a master goldsmith imparts his knowledge to an apprentice, who may come from outside the family.

Only men may become goldsmiths in the Asante tradition, and this in itself makes the fact that a woman was given permission to learn the technique quite extraordinary. In 1997, jewellery designer Johanna Dahm (Switzerland) lived in Ghana with Asante goldsmith Nana Poku Amponsah, the only goldsmith allowed to make jewellery for the king Otumfuo Opoku Ware III. He taught her the Asante casting technique, particularly the manufacture of rings, which was his speciality. Not wishing to copy the techniques and specific designs of the Asante, Johanna Dahm developed her own method and characteristic style. Her rings can rightly be called a tribute to the Asante.

Kundan

The ancient kundan technique is still popular in northern India. Jewellery made using this technique is expensive. kundan literally means pure gold, and this jewellery is also always set with precious stones like diamonds and rubies. It is, however, no longer reserved for the aristocracy. The growing middle class also has the means to buy exclusive jewellery nowadays. Kundan has therefore grown into a popular genre, a proud reference to the traditional royal northern Indian identity. These days, however, there is greater demand for jewellery that conforms to certain fashion trends. Both traditional kundan jewellery and more affordable versions are therefore available.

In Jaipur, it is mainly the major jewellers that can afford to keep old, renowned crafts like kundan alive. Amrapali Jewellers in Jaipur was established by two Indian art historians, Rajiv Arora and Rajesh Ajmera. Since the 1970s, they have been studying regional goldsmithing traditions throughout India and buying traditional items. Unlike most jewellers, they do not melt them down but dismantle the jewellery to study it or incorporate it into a new piece with a contemporary design. In this context, their collaboration with Manish Arora is also interesting. Arora is a well-known Indian fashion designer who works in Paris, and his designs are worn by Bollywood and Hollywood celebrities. He draws inspiration from Indian crafts and traditions, and incorporates them into a contemporary look. For several years he brought out a line of jewellery in collaboration with Amrapali to accompany his ready-to-wear collection. The jewellery of Manish Arora is a contemporary version for a fashion-conscious clientele made using less expensive materials, which has given this traditional Indian craft an international platform.

Pounamu

Gold has been a highly prized material for many centuries. Yet, the value assigned to it is not self-evident and the precious metal is not been considered valuable everywhere. To the Māori of New Zealand it was pounamu, or jade, that was precious. Pounamu is rare and could only be found at a few locations that were difficult to access. The sea voyage was hazardous, so pounamu was carried on foot over the New Zealand Alps. This all contributed to the great value placed on pounamu in Māori culture. The material is difficult to work with, which also increases its value.

A traditional application of pounamu is the hei-tiki. Hei means ‘to tie around the neck’. What tiki represents remains a mystery but is thought to be an abstract human figure. Tiki pendants are often given ancestral names and are treasured heirlooms transferred from generation to generation. It is this genealogical provenance which Māori call whakapapa. With usage hei-tiki accrue many whakapapa stories over generations which increase the cultural value. Historic or contemporary tiki are considered by Māori as an ancestral link or even a manifestation of an ancestor. To date, tiki are an important symbol of Māori identity worn by both men and woman today.

Whakapapa is a concept that plays a major role in the work of jewellery designer Areta Wilkinson (Aotearoa/New Zealand). Wilkinson creates ‘cross-cultural alliances’ combining international goldsmith traditions with a Māori worldview. Her jewellery is a contemporary investigation of taonga tuku iho meaning ‘heritage handed down’ and explores ancestral connections by responding to the shadows of historic Māori adornments. In this way, her jewellery has a whakapapa that connects with both the history of Māori and a contemporary Māori identity.

Shells

In places by the sea, shells are an important element of body decoration. The use of shells in jewellery has particularly reached a highpoint in Oceania, with its thousands of islands in the Pacific. Each region has its own kinds of shells. The highly prized mother-of-pearl shell occurs mainly in eastern Micronesia, and giant clam shells are found mainly in Melanesia. Historically, materials that did not occur naturally in the environment would be obtained through trade or brought back by travellers. Shells were transported from the coast to inland areas, while feathers travelled from inland to the coastal regions. But shells were highly prized at the coast, too. Diving to collect the shells was a hazardous business, which only increased their value.

In various parts of Melanesia, flat discs made of giant clam shells into which finely carved geometric tortoiseshell figures were inlaid, were worn on the chest or on the forehead. The value of the kapkap, as this jewellery is known, was determined by the size of the disc and the skill of the maker. The more delicate the tortoiseshell motif, the more valuable the piece. Today, kapkap continue to be worn during festivities as a sign of wealth. Shells are also popular with the jewellery designers of today. For jeweller Alan Preston (New Zealand), shells, stone, seeds and fibers are as valuable as the more traditional gold and silver. He combines his skills as a goldsmith with techniques and materials from Oceania. Preston sees his work as a modern-day continuation of the historic jewellery tradition of Oceania, a tribute to that tradition and the people of the Pacific.

JEWELLERY – Made By, Worn By / SIERADEN – makers & dragers

13 December 2017 to 3 June 2018

Museum Volkenkunde |Steenstraat 1 Leiden

Open: Tuesday to Sunday, 10:00 to 17:00 and on Mondays during school holidays

The museum is closed on 25 December, 1 January and 27 April.

See the website for the latest information, events and special activities.

Buy tickets online at www.volkenkunde.nl

Vanessa de Gruijter, Assistant Curator.

With many thanks to all the curators of the National Museum of World Cultures for sharing their expert knowledge.

OBSESSED! Jewellery in the Netherlands is a festival that unites the best events focussing on jewellery – exhibitions, symposia, fairs, book presentations and open studios – into one intriguing programme, put together by Current Obsession.

OBSESSED! runs throughout the whole month of November’17, in various cities across the Netherlands, accompanied by a special free edition of Current Obsession Paper and an interactive webpage.