Kellie Riggs: Tell me about your first memories of jewellery in your life.

Göran Kling: I have this face blindness – it’s called something I can’t remember – and it’s not so bad now, but when I was a kid it was a lot harder for me to recognize people. So at a super early age I started memorizing the members of my family by the jewellery that they were wearing. My first memories that I have are of jewellery. My mother had this silver rose, and my aunt had a triangular amethyst, and my grandmother had a long silver necklace with a ball on it. And that somehow, got stuck in my head or something, that I automatically remember what people are wearing. It’s an obsession with jewellery that I have. And I just always knew somehow, that I was going to make jewellery.

So it’s about the jewel being a part of something bigger than itself, maybe it’s not even about the jewel but what comes with it: feeling and culture. We’ve talked about hip-hop before as a bigger example of this.

Hip-hop is a really interesting example. I think sometimes it can be perceived to be superficial and dumb, but on the other hand it’s the world’s biggest cultural movement ever. And it’s somehow kept this subcultural status. How did they do that? But it still has to be at the level where it can reach a broad audience. That’s a really good example of hip-hop being so narrow in a way, that a rap song can have all of these references that you can only understand if you have sold drugs in south Chicago, for example. Somehow that’s super interesting for other people. But as a business: ‘I’m gonna write this song, and rap this shit, nobody understands the words, what they mean…’ so maybe they google it. And maybe not also. I think it’s about mystery. It has to be seductive.

During your recent talk in Germany at the Schmucksymposium Zimmerhof, you said that you like jewellery for all the un-sophisticated ways it makes our lives just a little bit more glamorous, that someone wears a certain ring because it makes them feel special wearing it.

The thought behind this is that jewellery is not practical in any sense. It doesn’t have this practical function that clothing has. And therefore its unnecessary somehow, that’s the key; it’s the whole thing that separates jewellery from everything else for me.

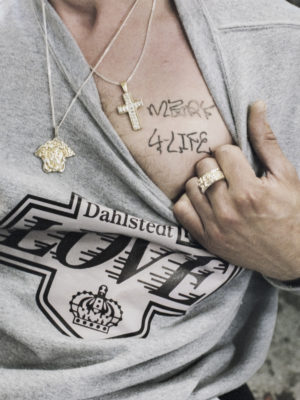

I guess it’s this unsophisticated or irrational feeling, like holding a ring and rubbing it, this shiny surface, and this really blatant… I’m looking for a word for a symbol that has meaning but isn’t like a skull or a heart or something stupid, these classical jewellery themes – there is this fine line between what’s really shallow or superficial and what is so deeply connected to humanity, what we experience. All these ideas of life, death, religion, love.

Actually the first piece of jewellery I ever bought was this double-headed skull ring with a snake running through the eye sockets. And I can remember looking at it, sitting in the car afterwards. Even as an 11 year old I could understand that this had a connection to something; heavy metal, music… but then it also has this other meaning, this connection to life and death, what a person looks like when their flesh rots away. And I think since then I’ve been trying to recreate that feeling of holding that skull ring for the first time. The power of jewellery is that somehow, this attraction, desirability, which is unpractical in every sense, and also super illogical.

What’s jewellery about for you?

I’m interested in what happens with the jewellery that you wear everyday, when jewellery becomes an extension of the wearer’s identity. That’s also the reason why I want to work with commission – jewellery especially made for one person. I hate this idea of jewellery being by itself. I’m only interested in the connection between the person and jewellery. For me the gratification is about someone that I make something for, the piece then becoming a part of this person. That’s amazing.

You’re Swedish and thinking about these things, so wrapped up American culture. Why?

Ok so I’m obsessed with American culture to begin with. I was born in 1978 and Sweden was still super socialist then, still very much behind the iron curtain in a sense, also my parents were super political, so we didn’t have all these things. Not poor, but we didn’t have things that were considered ‘bad’. For example, my mom didn’t want to buy American sneakers so she bought shitty, shitty Swedish sneakers and they were not cool and they broke two weeks after. It was so bad.

I couldn’t have t-shirts with prints either. There was this store where I lived, and they had this iron-on print machine where you could go print a t- shirt. And they had a thick catalogue with all different smileys: smileys shot in the face, smileys taking drugs, smileys on the beach surfin’. And each print maybe cost a dollar, but my mom didn’t let me have them. And of course the spoiled kids in school had like fifty of those printed t-shirts. So instead, my mom would draw on t-shirts for me.

Then we got cable TV when I was 10 or 11 and all of a sudden we had MTV and the Simpsons and (M*A*S*H). Before that everything was a grey scale, brown, there were tin tones on everything. And I remember so clearly when everything changed, when all of a sudden we were exposed to this other culture that had all these things that you knew somehow were cool and everything else was shitty.

How did you know they were cool?

I don’t know, but I guess it’s just packaged in a nice way for young people, it’s shiny somehow. Like the smiley face is bright yellow… and because it’s you not wanting to be like your parents.

In a funny way you’re doing what your mom was doing, you’re making these things now yourself, on your own terms.

I love that, I had never thought about it in that way. But it’s true.

How do you pick the images you use in your jewellery? What’s got to be there?

It’s hard to say what goes in and what doesn’t, but I think for me things can’t be too connected to other things you’ve already seen. This whole thing about pizza for example, there’s been so much shit. Or imagine how many mustache products there are on Etsy at any given time, at any given second. Someone is buying a mustache product on Etsy… right now.

So it’s difficult and suggestive to use these images, to pick them, things that are connected to me, and that I have a connection to. Meme-quality; for me, there’s got to be a meme quality to it. Jewellery itself has meme- quality. We use jewellery to read people, right? And therefore it means to be in on something together so the jewellery can be easily understood. But not necessarily by everyone, but by whom you want to communicate with. So if you have to give a long explanation about its making process or all the

other qualities jewellery can have like material blah blah, then that meme factor doesn’t work.

At Zimmerhof we were riffing a lot, I was throwing out images, one after the other, that you would say yes or no to, as way to understand how your brain decides what may or may not work as a piece of jewellery. What did we end up with?

The things that stuck, from the top: a saxophone, Y2K, ‘My Bad’, ESPN, and LAPD. It’s like you got 5 out of 5,000 right, but I think that’s where you have to be. And I think this I what I do constantly with myself.

Is there a common thread?

A lot of my images are connected to a low cultural value and it just so happens they are American, it’s not my definition though. At least in Sweden, there is this clear definition of what is highbrow or lowbrow, fine culture or pop culture. Swedes think American culture is lowbrow. All of Europe does. No one has ever told you this? Coca Cola? This is the symbol of bad culture. Capitalism, you could call it that, the two poles, capitalism and culture. It’s like the opposite of timelessness, this Swedishness of clean, geometric shapes, nature and pureness. I am questioning the frame around what is allowed to be used in traditional handmade jewellery.

The Chicago Bulls?

I like the championship rings, aesthetically. And I like this connection to sports also, it’s kind of a contradiction for me somehow, jewellery and sports. I also like the format of the ring because it is limited. It’s more about ownership, accomplishment. Championship rings are quite big and it’s this idea of men wearing them that I like too. So while madly googling these championship rings I found this whole market for replicas which I think is really strange because obviously they only exist in one, only if you win the championship. And these replicas exist in different qualities – from the best quality, gold and gemstones – to the cheapest quality, pressed copper. Doesn’t even look like the real thing. For me that’s really interesting, the layers of the imitation. I am referencing this idea of the replica.

Was your India trip in January 2016 to northern Mumbai part of this interest?

Yeah it is connected somehow. It had to do with authenticity and what is defined as real jewellery or fake jewellery. I think often it’s connected to western craft; the idea is that handmade jewellery in the western world has a higher value than the rest, and it’s based on the idea that things are made by machines in Asia, so that’s a different type of jewellery. But in reality, everything is made by hand, only the place is different. That’s what I found out by going there. I was interested in seeing where what we call fake, imitation or machine-made jewellery actually comes from. What is the real difference? There is a difference in how the story is told about these things, but I wanted to find out what the physical difference actually was. And what it turned out to be was that it was made in exactly the same way as we make it, with exactly the same tools.

How else is your position in or your approach to the jewellery world different from those around you?

I always have one foot in the traditional jewellery world and one in what we call the ‘contemporary jewellery’ world I’m not an artist-artist. A lot of jewellery artists are artists who happen to make jewellery, do you know what I mean? My thesis at Konstfack, {called Jewellery Be Like}, was about this interaction between jewellery and customer, or maker and wearer. It’s been lost in Contemporary Jewellery and that’s why it’s of interest to me. So what I want to do is basically take the traditional way of running a jewellery practice but do it in a version that feels interesting for me and maybe for people today. If you’re 25 or 30 years old, you’re not going into traditional jewellery shops and buying stuff on consignment. And on the flip side, the problem with galleries and collectors and Art Jewellery Forum and the whole contemporary jewellery world, is that it’s limited.

So if neither of those worlds work for me then there needs to be an alternative platform to communicate my jewellery. If I don’t have a shop where I sell or if I don’t have gallery representation then I need to display what I do somewhere else.

On social media?

What platforms like Instagram offer is an opportunity not to have to participate in these other conventional or commercial spaces. All of a sudden makers can decide for him or herself who their audience could be. Social media is two-way communication also, which means you’re interacting with an audience throughout the process of using it. It’s the opposite of that artist who is working secretly in their studio for two years and then they have a gallery show.

So you’re thinking about your audience and discovering who it is simultaneously, as you use these platforms?

Yeah. If you open the communication between audience and maker then that creates energy and momentum. If you’re interested in your audience and they are interested in you, then that’s the key. But that’s not necessarily a new idea, because jewellery making has been based on commission forever.

Walk me through the process of getting a new commission.

Maybe ‘made to order’ is a better way to explain it. So people will direct message me on Instagram about the jewellery, and then we will make an appointment to meet in my studio, or somewhere else. And we usually talk about jewellery; what it means to them and to me. I ask them a lot of questions about jewellery because I’m interested in their relationship to it. This is what fuels me.

And then based on that, the conversation turns into some kind of conjunction of images or symbols; I try to establish some sort of proposal of references from which we’ll then agree on one. And based on that, we come up with a shape, the expression, size… it all gets decided. We try to come up with an idea that would be interesting for them and for me at the same time. I’m not making whatever people want. The jewellery is for people already interested in this aesthetic, it’s not like a blank page; they’ve seen something that they like but we can make it into something for them specifically. My Instagram is like a catalogue yet open for being personalized or customized.

Talk to me about the future and what that is for you.

I basically only think about the future, professionally I mean. I don’t have any aspirations to do anything other than make jewellery. I want to keep doing commission work. Ideally if I could choose exactly what my professional life would look like, then I would work similar to a tattooist. These new ones that travel and post on Instagram and show up somewhere and they have all these people already interested in having a tattoo, you’re booked before you even get there. I could do a pop-up thing for three days somewhere, like coming to wherever Germany and have a stall. You can also take up commission work on the road, if you have some kind of catalogue put together, like a flash, Then you could send the ring to the client a few weeks later.

Do you find that using social media circumvents some of the elitism often found in both traditional and contemporary jewellery circles?

Yes, it’s the thing the Internet changed. The communication or connection between maker and audience is no longer based in the physical world, which is what the galleries or shops had decided before. That’s all been dissolved by the Internet. The connection doesn’t have to be dependent on these gatekeepers that label what you do anymore; it never mattered what kind of jewellery you made, if you’re represented by a gallery it would mean it’s contemporary art jewellery, or if it’s in a store then it would be labelled something else.

I’m not interested in these kinds of labels for my jewellery – for me the label is defined by the person that chooses to wear it.

This interview has been condensed and edited from a series of conversations that began at the Schmucksymposium Zimmerhof in Bad Rappenau, Germany in May 2016 and first published in Current Obsession Magazine’s #5 Vernacular Issue

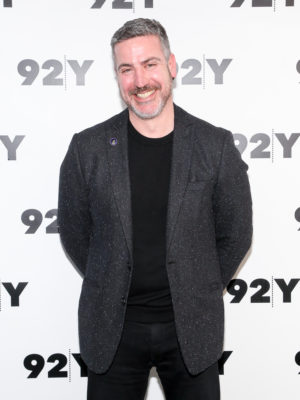

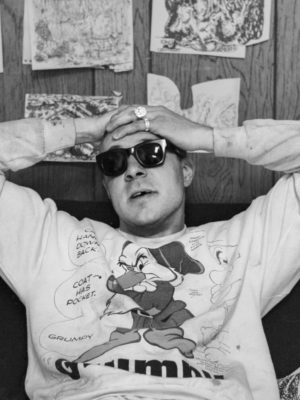

Jewellery: Göran Kling / IG: goran.kling

Model: artist Love Dahlstedt / IG: lov3dahlst3dt

Photography: Mikael Krantz / don’t have one (shoots analogue!)