CO: Could you tell us more about your exhibition ‘A Hologram of a Diamond’ and how it challenges notions of authenticity and value?

Moniek Schrijer: Contemporary Art Jewellery challenges our perceived value in multiple ways, often deconstructing concepts upon which the jewellery industry is built. This body of work explores holograms and diamonds, both of which can be considered illusions – illusions of the flat plane and illusions of rarity, preciousness, and worth. At the same time, this work also speaks to contemporary tastes, the age of bootlegs, riffs, post-copyright replicas, fakes, imitations, counterfeits, and tropes that have been reinvented and reimagined.

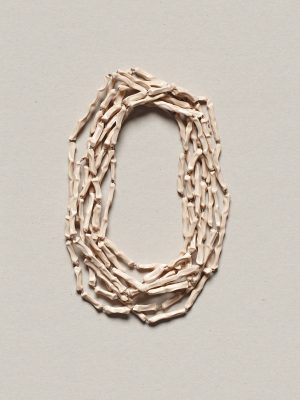

Twenty-five works are part of this project. Ten of them are glass plate reflection holograms set into aluminium sheet metal in the shape of gemstone cuts. Holography has captured the three-dimensionality of the diamonds within a flat plane, recording the gem cuts, optics, and illusions with opal-like effects. The other fifteen works are necklaces and pendants, which house 42 replicas of the world’s most famous diamonds, from ‘The Great Table’ to ‘The Taylor-Burton’.

CO: What inspired you to use laboratory-created replicas of famous diamonds and traditional reflection holography in your artwork?

MS: I have always been a fan of replicas. They are a strange sort of thing—a stand-in or prop for the real. The hologram aspect came first, as the sparks for this project started in 2019. This was after being included in ‘Non-Stick Nostalgia: Y2K Retrofuturism in Contemporary Jewellery’ at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York, curated by Kellie Riggs. This is where I exhibited my first jewellery works that used repurposed hologram skull glasses.

A fellow jeweller mentioned that there were a few holographers in New York, including a museum. I was only able to visit one holographic studio while I was in New York, but that visit led me to the question—what would I make a hologram recording of?

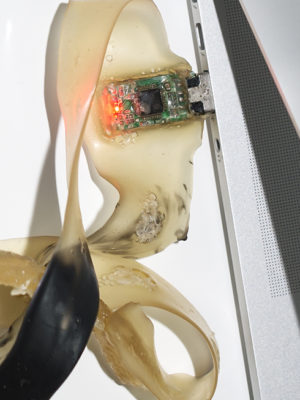

Also, around 2018/2019 is when I started to explore stone-setting methods that do not require the addition and soldering of metal. Instead, I hand-pierce flat sheets, creating tabs and prongs which hold the stones or objects in place. This has become a bit of a signature, and without this style of stone setting, I think I would have struggled to work with these massive laboratory-created replicas.

This body of work explores holograms and diamonds, both of which can be considered illusions – illusions of the flat plane and illusions of rarity, preciousness, and worth.

CO: How do you approach the creation of your sculptural necklaces and pendants? What role do vivid colour and textural detail play in your work?

MS: The flat cut forms are developed and planned out on paper before being cut into metal. For the larger stones, a test cut in copper is made to ensure I cut and position the tabs correctly. I also arrange things on a mannequin, which helps to see how the pieces sit and fall on the body. Colour wise, I built up layers of patina paint to bring further complexity to flat areas of the pendants and necklaces.

The luminosity that the original surfaces of silver, copper, or brass bring produces a depth unique to painting on metal. When light is introduced to these works, other elements become present. Reflection and refraction create geometric beams of glinting light, revealing new transparencies, colours and fine details allowing the set stones to glow beyond their border.

As light plays a vital role in this exhibition, different textural elements have been incorporated to force the light to bounce. Textures have been added through high and low polishing, metal texturing, and chain making.

CO: The Jewel Room is described as echoing the vault-like spaces where valuable objects are often secured. Why did you choose this theatrical staging of the show?

MS: My main objective was to create an atmosphere as vivid as the jewellery works that would further contextualise my pieces. To clarify concepts, I built a miniature version of my vision for the gallery space, incorporating existing details and architectural aspects of the building and gallery environment.

This immersive installation borrows various elements from vintage and recent high-end jewellery store fit-outs, film and cartoon concepts, secure storage and vaults, while also taking inspiration from jewellery rooms within museum spaces.

CO: For this exhibition, you collaborated with Sophia Smolenski on a custom-made mounting for your jewellery. How did the collaboration come about?

MS: Once some of the works were complete, and as I started thinking about their presentation, the idea of the pieces hovering in space on mounts became the prevailing thought, replacing any original ideas. These mounts evoke the feel of noted jewellery rooms at museums like The Smithsonian and the V&A. It was fortunate timing, as Sophia had just approached me about an exhibition called ‘Offering it Up’. In this show, artists respond to a mount Sophia had created for an object that was unknown to the artist. Quite a few jewellers from Aotearoa are involved; you can follow along via the ‘Offering it Up’ Instagram.

CO: What challenges, if any, did you encounter during the creation of this body of work, and how did you overcome them?

MS: Funding this project, coupled with the pandemic, presented my biggest challenges. I definitely felt blessed to be in Aotearoa/New Zealand, Still, before any lockdowns, Creative New Zealand (our arts council) cancelled all applications, and this project fell into that cancelled pool. Consequently, I had to re-apply, not once, but twice. So on the third try, I was successful. This project was only possible with that financial capability.

The project’s course changed along the way. From being unable to return to New York to produce the holograms to having items broken in the post, the journey had a few obstacles, but that time all seems a bit blurry now.

CO: Are there any specific cultural or historical references that influenced your artistic choices and concepts within ‘A Hologram of a Diamond’ and ‘The Jewel Room’?

MS: Quite a few references are embedded in the works. When the famous diamond replicas arrived, the sheer scale of their ridiculousness was immediately apparent. This realization almost invited a certain level of absurdity, as the diamonds seemed so novel. Elements of form and shape are drawn from toys, film, cartoons, industry, and the original settings or origins of the famous diamonds. Each diamond has an often loaded and turbulent history.

Initially, I tried to incorporate more of that historical information into the work. However, this approach proved to be ineffectual. Whose account was I accessing? Instead, I let the jewels’ cut and colour determine aesthetic choices.

Photography by Ted Whitaker.