Kahn’s work is characterised by his willingness to push the boundaries of materiality and form. Rejecting the notion of cold minimalism and bare functionality, he instead creates pieces that are driven by narrative and emotion. From his sculptural installations to his functional furniture designs, every piece tells a story and invites us to explore this whimsical world that is both familiar and yet entirely new.

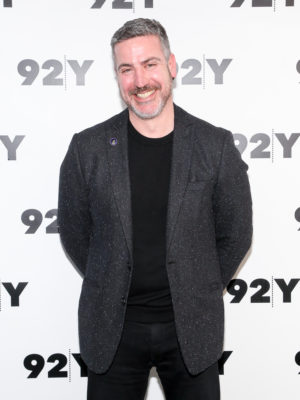

We had the pleasure of sitting down with Misha to gain a deeper insight into his background and creative process during an inspiring interview. The interview is composed and conducted by the participants of GEMZ, CO’s very own talent development programme.

Current Obsession: What were some of your biggest milestones? Thinking about the transition from part-time to full-time artist.

Misha Kahn: It was a cantankerous and odd transition. I moved to New York and on my days off I would go and make, I had a little table in a shared studio. I started doing shows in friends’ warehouses and everything was informal and then things just snowballed. I started working with a gallery, and I had a show there and then I got into a museum in New York and a few other institutional places where my work was included. From one of the shows, Friedman Benda Gallery, reached out afterwards and they wanted to work together. They purchased a big chunk of work, and so I had some money to produce a whole show. That was when I really transitioned to doing it full-time; at the time it seemed like a temporary state change but then I kept building on it.

I’ve always felt like, it started with a seed and now I’m, just building from it. My practice is always constructing from the thing that came before it.

CO: Throughout these years of practice, what keeps inspiring your design concepts?

MK: In the studio, things just snowball, so often when you see the work you think ‘How did it get there?’ and it is always from the thing right before it. When working, you have material ideas which you experiment with and explore. These experiments then merge with feedback and ideas you have. I’ve always felt like it started with a seed and now I’m just building from it. My practice is always constructing from the thing that came before it, which is both fun and burdensome. I am envious when I see people’s works that feel like each show is a clean page and they are starting from scratch. I think a lot of people do intense research in that sense to then develop a new thing.

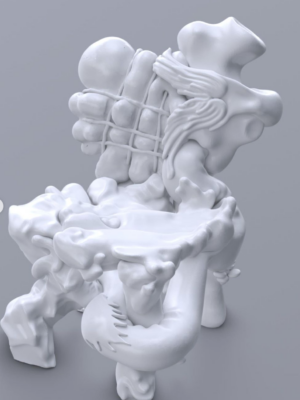

A selection of Kahn’s work from various exhibitions and collections.

CO: Which craft puts you in the zone, which one do you find meditative? Is there a spiritual aspect to your crafting?

MK: Sewing relaxes me, I make rough sketches and then immediately sew them. Every part of the process is cathartic and straightforward. I work on so many projects where there is roping together of different components and fabricators, and the timelines are long. None of it is tactile or offers the satisfying immediacy of making whereas sewing does.

CO: Your work looks like renders from a virtual design process without being limited by gravity and material properties. Could you elaborate on your working method? How digital or ‘manual’ is your design process?

MK: I sculpt things in virtual reality where there is no gravity; in this context you could make anything. I try to create the feeling that the objects are light, free, and floating way. I keep trying to push that part, we were talking about getting a float tank that would have a salt bath or having a sex swing to be suspended in. So, we can feel weightless when sculpting, to try and push that feeling as far as we can.

In terms of fabrication, we mostly 3D print. Sometimes a robot will mill parts and the fabrication is onerously done by hand. The parts are patched together, filled in and smoothed. So, part of my work is still based in a very stubborn handmade way. Something about manifesting objects so they feel like they’ve sprung straight from the computer that feels nice to me.

CO: How do you find the balance between free form and functionality in your work? Do you sacrifice the form over the functionality or vice versa?

MK: There have been times where I think I’ve ruined something by randomly bludgeoning the top off to make a table. A lot of the time, I will block off the functional part and try to work at it in the most surprising way I can, leaving this negative space that you know must be there. In the case of the ammonoid chairs, I would think about how these forms could arrive at that negative space in not the usual way. In those instances, I think it’s the most successful cross-pollination because it’s the void that is the function.

There are also times when it’s about this idea that you are in this parallel world, and you are creating what that object looks like in the world. It’s not about being in opposition to normalcy. It is just free from preconceived notions of say, what a lamp looks like and is, and it’s free from this relationship to functionality.

CO: We are conditioned by the functionality of jewellery and so can feel limited creatively by this and I was wondering if you relate in the same way?

MK: I haven’t made a ton of jewellery, but I love it and I am making and thinking more about it. With jewellery you don’t have to apologise for scale, I think there is a freedom that comes with that but then for me it is important they feel super wearable and desirable. I have been exploring the idea where no material is worth more than the other, so it’s just about choosing the one that is right for design. So, there is a combination of low and high brow materials, but the juxtaposition that wasn’t relevant and was a never joke. It was about staying true to this way of thinking as all materials being equal and what materials complement one another.

CO: By 3D printing the object on a smaller scale it becomes something completely different. How do you relate to scale and scaling in general?

MK: I make a lot of miniatures, in my office are tons of tiny versions of things we later made. A painter friend pointed out to me that the gesture you make when something is small can be hard to make as a big gesture and vice-versa. You can make a mark at certain scales that you can’t replicate in a different scale, but you can translate it which lets you work with scale in a surprising way. I don’t think it is a theoretical or conceptually important reason for doing it, but I think it’s a good trick to arrive at a unique place. For instance, when sculpting jewellery in VR I was building it from the really expanded view as if I was inside the piece.

Kahn’s use of VR in their design process.

CO: How important is it to you that others can read your topics? How important is it to you that your work is understood?

MK: For me and my soul, it’s not important, but in a financial sense, it is important. I feel beholden to ensure the work is readable or understandable enough so people can appreciate it and want it. There’s a financial reality of running this studio because there are so many times when you can see the furthest end place that you can take something, and you just want to go all the way there. I’m always the one to bludgeon that vibe because if the audience feels ostracised from the work, they won’t purchase it. It helps if they can follow the breadcrumbs and connect to the creative process.

CO: How do you approach materials and the technical kind of manufacture of them? Do you learn it all in house or do you rely on industry collaborations, funding, or engineers?

MK: When I first started working with cast metal, I went and worked at the foundry for a month, and I was just trying to do all these experimental things. It was lucky being there because if I had just presented my ideas, it would have just been a straight no. There have been instances where I would spend a lot of time with people because I didn’t have the skill set or the knowledge, but my objective wasn’t immediately obvious, so we had to think of a different approach.

I’m a Gemini, so I’m always building two things at the same time.

CO: In the future, what are you excited about material wise or technologies? What are you looking to integrate into your work or is there anything for the future of your practice?

MK: I’m a Gemini, so I’m always building two things at the same time. This is not my idea, but people in the studio have been looking at the lasers in the 3D printers and building an animation from them that can be projected, creating something very immersive and experiential. It is working, but there is an insane amount of troubleshooting. I waste a lot of the resources in the studio on these fool’s errand R&D projects.

CO: You speak of your objects as independent beings at times. How has your relationship to them evolved from conception to completion? How does this play into this ‘other world’ or ‘parallel universe’?

MK: Many people’s creative practice focuses on the importance of expressing themselves and what they’re trying to say. My approach, however, gives me a little more distance. The objects are part of this endeavour and have their own autonomy. I like it when objects feel personified, but not in a super-literal way (although some of them are). It doesn’t mean that they necessarily have a bunch of legs or eyeballs. They feel sentient, as if the object is its own being and could walk away from me.

They feel sentient, as if the object is its own being and could walk away from me.

CO: What decides the titles for your work? — they are very poetic, dreamy.

MK: My mum is a writer, and for some shows, I’ve just told her to go crazy and write great titles, and she’ll just go off. Many of the objects have a synthetic touch, something that gives them an evil edge. A title can balance this, grounding the objects in something contemporary yet still floaty. You may see the piece in one way, but a title can pull you in a different direction and make you see it in a different way.

Kahn’s work in a gallery setting alongside jewellery & painting.

CO: By collaborating with professionals from other disciplines, what’s the most memorable positive and negative experiences: how do you resolve conflicts and balance the ideas with others?

MK: When working with someone on a project, you begin to trust their sensibility. You may have an expectation of how something will look, but it will always be different, and sometimes it can look ten times better than you imagined. Whoever is making it must cumulatively make a million micro-design decisions, and those all add up to push it in a different direction. You don’t always appreciate the difference straight away, but in retrospect, you realise it was better this way.

Of course, there are times when it isn’t at all what I imagined, but the audience response is positive, and you come to accept it. In the end, these differences can add to the process, and it feels holistic. Sometimes people think that just because something is crazy, I’ll automatically like it. They have a perception of my work as anything goes because it’s very loose and free. Whereas, in reality, I’m very controlled about all these parts. So when someone does something so left-field, it’s frustrating. There have also been times when it’s felt like a tragedy, and pieces have been ruined.

CO: In your work there is a theme of searching for the distinctively human. Would you say that there is a sense of dismantling western ideas of design in favour of non-western ideas and if so can you elaborate on this a bit?

MK: In a sense the western ideas are industrialisation and modernism. The idea that mass producing objects and exporting ubiquity is positive; thinking that everyone having a decent life involves producing at scale and making millions of the same things. I am fully in opposition to this approach, it is wrong ecologically, mentally, and emotionally. There are many cultures with a different sensibility, especially to Americans.

There are exceptions within the western world. I love working in Italy they have a sense of family; artisanship and that industrialisation should never take away the hand. In Italy, there exists a view within craft that using your hands is valuable not menial; you would never be embarrassed to say my family makes shoes for example. In the states we don’t have this culture, its focused-on production and efficiency. I think making objects in an intuitive way and valuing individual objects is comforting and is perhaps the best-case scenario.

My takeaway is don’t rush, there really is no timeline or a clock.

CO: How did you begin your journey into the art/design gallery world? Specifically, regarding museums and private collections.

MK: Disclaimer, I had this experience and thought it was the only way to do it. But I have watched others do it in a really different way. When I started so much of the reason, people started buying, collecting, and showing my work was because it had this youth enthusiasm around the shows. The shows felt like big parties, they were packed and not with collectors and curators. It was just a bunch of people who were excited about making this type of object and making things in this way. I think because of that enthusiasm, other people became interested, the museums and private collectors started showing up. I have followed that thread and have put a lot of the energy into making work to appeal to those people (collectors) but I feel like I’ve like lost as a swath of that enthusiasm and so it’s a tricky balancing act.

CO: Is there anything you would have told your younger self, right after you have just graduated Rhode Island School of Design?

MK: I feel like I’m at the end of RuPaul when they cry dramatically and talk to their younger selves. I approached my work with a lot of energy even though I didn’t know where it was going or what my goal was. I started making things so immediately after school, and so I’ve always been a bit tethered to that start. All these elements I began with are still at the core of what I do. On the other hand, I’ve watched people around me who started their career ten years later, they weren’t making or showing things publicly and then there was a moment when they just went for it and started their career. Those people can go in with so much precision with what they want to achieve with their practice, they are laser focused on what’s trying to get accomplished. I envy this experience because I don’t feel like I can wipe my slate cleans.

My takeaway is don’t rush, there really is no timeline or a clock. Sometimes coming out of school you think you need to hit the ground running and you feel this pressure. It is better to have your work be exactly what you want it to be, take time to get your thoughts in order and your output will be better for it. We are in such a state of sharing everything, but your work can also just be yours and that is valuable.

CO: Misha thank you very much again for being so open and honest.

MK: It was nice to meet all of you. Thank you for having good questions, bye everyone.

This interview was edited for clarity.

Cover Image by: Nina Moog for Current Obsession, 2022