Though this celebration has for years been a go-to meeting point for the jewellery community, it’s not the only jewellery event of the year by far. In fact, it seems that ‘jewellery weeks’ have been springing up all over in recent years. And yet, Munich has its mystique. Contrary to the oft jewellery-adjacent world of Fashion, jewellery weeks do not serve the same practical function as fashion weeks – debuting new collections to buyers, aficionados, and press, who do their part to inform the coming season of trends, and so on. No, jewellery weeks are not nearly so singularly focused. Munich in particular.

An effort to determine exactly what the draw is, however, quickly scatters with the realisation that Munich is many things to many people. It’s big. Really big. And I suspect that no matter when you come to it for the first time, whatever it was then is what it will always be for you: the first impression becomes your definition.

Many are the debates about what it ‘used to be’, and what it ‘should be’, as it inevitably morphs over the years. Personally, I’ve never been certain what exactly that is. Having encountered it as many do, as a jewellery student at an art school, I saw neither division nor association, just a cloud of hysterical jewellers. (They’re actually a lot of fun once you get to know them.)

‘Munich’ is the trade fair for craft (the International Handwerksmesse) where you can see world-class jewellery and lederhosen side by side; it is the juried selection of the Schmuck and Talente competitions, (curated this year by Helen Britton); and the panel talks, and the gallery openings, and getting to see your friends in the field, from New Zealand or Finland or California. It is waiting at the Pinakothek to see the incredible work of a legacy artist, but sitting first through a befuddling hour-long speech in German, feeling like a character in the waiting room scene of Beetlejuice. And it is thronging into a dinner with a few hundred other jewellers, hoping for a seat at a common table, for beer too big to drink and a meal too big to eat, over the din of gossip on a hundred tongues – and loving it.

In its many iterations, Munich is like a living timeline – with every moment of its evolution coexisting at once, in all the messiness that entails. Defining what it is may be impossible, but perhaps now is exactly the moment to catch a glimpse of what it could be.

Which brings us to the rest of the story… The off-site events.

With expos subject to a juried selection process, naturally some aren’t selected. In 2002, a group of such artists decided to plan an exhibition of their own – entitled Salon des Refusées, (Salon of the rejected), a direct reference to an 1863 exhibition organised to appease the artists whose work was rejected by the Paris Salon, the official annual showcase of French art of the day. A group show featuring Peter Bauhuis, David Bielander, Felix Lindner, Norman Weber, Christiane Förstner, and Andi Gut, the idea for the now infamous show came over a dinner less than a month before the fair. Bauhuis, who at the time was, “fooling around with html” made a digital invitation showing Édouard Manet’s, Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe, (historically cited as the most radical and shocking work of the 1863 Salon) and drew rudimentary drawings of jewellery on the figures in the painting, that would disappear when you ran the cursor over them. He found an architecture firm with an empty office and negotiated use of the space for a night. As Bauhuis simply puts it, ‘You got a space and then got some beers, and you had an exhibition.’

This unofficial, off-site show was an instant success in both popularity and attendance, and in short, became the new model for artists who don’t fit into the constraints of the establishment events to this day. For the last twenty years, these events have proliferated to the point that, at this stage, no one can possibly see them all. I looked up Peter Bauhuis to get his recollections of that show, and his thoughts on how things have developed since.

Peter studied at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Munich, in the 90’s, and as a Munich local, has a very different perspective than most – one that includes quite a bit of the early years. He relates memories of when the fair was at a location in the city centre, as opposed to its current home in the sprawling convention centre Messestadt, so large it has two train stations devoted to it; and the traditional Saturday jewellers’ dinner was 25-30 people in a Greek restaurant, sat around one big table. A lot of growth in two decades.

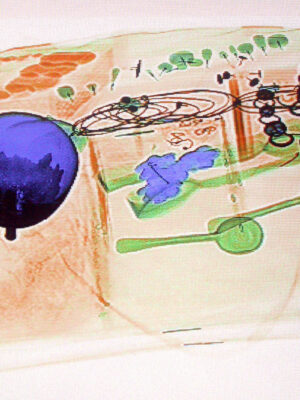

Building off the momentum of their first show, came 2004’s Salon International, held in the gallery of the Town Hall of Munich. The invitation featured an x-ray of all the jewellers’ work that Peter managed to have made at the security gate at Munich International Airport. Again, not bloody likely in 2022.

Another interesting tidbit Bauhuis relates from the time, and in notable detail, was the presence of a mysterious group called ‘busper’, whose identity/ies were supposedly never fully revealed. “Busper,” they proclaimed, “ is the feeling before, during and after wearing jewellery.” and as early as 2008, began attempting to catalogue the various independent off-site events popping up in the wake of the 2002 Salon, then around thirty or so. Taking note of this growing off-site phenomenon, busper tentatively dubbed it, ‘SMK’ – and produced a calendar and map, and even a limited series of merchandise. Perhaps the most memorable was a series of buttons for the wearer to label themselves according to their respective role in the jewellery madness.

Maker, User, Collector, Gallerist, and Ignorant. (Image conveniently provided by Peter.)

It was an attempt to make the citywide events visible, but commercialisation of it never came to be, possibly due to factors like the undeveloped social media space of the moment, who’s to say…

‘Obviously it was too early,’ Peter opines. Alluding to Current Obsession’s 2015 intervention to establish a workable design – and fashion week inspired moniker for the off-site proceedings, and distribute information about the events Peter continues, ’I mean, it’s a great invention of Munich Jewellery Week to invent the term Munich Jewellery Week. Because there was no name for it…’ In fact, it had (and still has) many names, all of which were informal and at the prerogative of the user.

Though an easier choice for English speakers, certainly, it’s interesting to note that the naming of ‘Munich Jewellery Week’ was largely precipitated by a perceived need to claim a cyber space, such as a URL or social media handles, with which to promote and share the off-site events. Likely a greater boon, in terms of extending the awareness of – and accessibility to, the Munich festivities, beyond the inner circles and word-of-mouth information exchange of the early 2000’s.

On the pros and cons of the off-site expansion, Peter jokes, ‘In the end maybe each jeweller is sitting in his/hers self-organised show, waiting for people to come, but nobody can come because everybody is sitting in their own show.’ But at the mention of regulating the fringe, by selection or curation process, he strongly disagrees, pointing out that the ‘anarchy’ of the space is what makes it so essential. ‘I have the feeling that some people get really upset because there’s things happening that nobody can control. There’s no “quality control”. But I think that is a very good quality because who is doing the quality control, then? I think, to the argument that a lot of people make, that there should be a selection process – of course not! Because who is going to select the selectors?’

Ironically, back to 1863, many regard one of the greatest legacies of the Salon de Refusées, that it emphasised the need for an alternative to the restriction of the official juried exhibitions, lest the conservatism of the prevailing institutions of the day curtail the participation of new and more experimental contributions to the field, and ultimately dominate the public opinion on art.

No, no. Independent, un-curated and entirely without restriction, the fringe events appear to be the ideal counterpoint for the highly organised proceedings at the fair and museums, free of the prevailing standards or prerogatives of academy, fair or museum. And anyone interested can come, including locals and passers-by. Even the fair, though with a ticketed entrance, is open to the general public for roughly the cost of a movie.

This is perhaps one of the greatest advantages, points out artist and writer, Rebekah Frank, former executive director of Art Jewelry Forum. Selling books or hosting AJF talks, most of her experiences in Munich revolved around the fair itself – meeting gallerists, collectors, and lots and lots of students.

Practising on the West Coast of the US, Rebekah adds an interesting perspective on the American model of jewellery conferences, (say SNAG for example) compared to the European model (or Munich specifically). While the tradition of hosting from the same city every year allows the local relationships that make Munich Jewellery Week what it is, having multiple events spread across the city encourages movement, which lends itself to chance encounters and opportunities for face-to-face conversations from all walks of the field.

‘Munich is a real big fish in a small pond kind of situation – and those big fish are just walking down the street, and you can walk right up and talk to them – it’s amazing.’

As for the ‘off-site’ proceedings, Frank points out that the opportunity to independently stage an exhibition with access to an informed and engaged audience has a huge benefit for artists trying out new and experimental exhibition formats. She wonders openly however, if current attitudes couldn’t offer a more rigorous critical discourse – regarding, for example, when work is ready to be shown, and to what standard we hold ourselves in terms of showing exhibitions that ‘just aren’t ready yet.’ After all, the idea of a supportive community also includes the potential for constructive criticism about where we have room for improvement.

To that point, a recollection many share from 2019 was the spirited discussion of the glaring absence of representation of artists of colour within contemporary jewellery at large. Beginning with a Social Club panel discussion moderated by Ashley Wahba, called Intersectionality in Contemporary Jewellery, with speakers Leslie Boyd, Kalkidan Hoex, Roxanne Reynolds, and Namita Gupta Wiggers, and perhaps culminating with Tiff Massey’s acceptance speech at the AJF Awards. Such a gathering of the institutions and the independents at once creates the potential to launch such conversations to a powerfully cascading effect, and it’s tempting to wonder what a 2020 edition would have brought in the wake of that momentum- unfortunately we’ll never know. While in subsequent interviews, both those artists have revealed that they no longer associate themselves with the field of contemporary jewellery at all, if developments like the founding of the Crucible platform are any indication, it is clear there continues to be energy behind addressing the ways in which contemporary jewellery is subject to the same weaknesses and blind spots of society as a whole, bubble though it may be.

So, what will our next big drifts be, after the mental shifts of 2020/21? The content isn’t shying away from the serious conversations any longer. Artists openly explore issues of social inequity, as well as death, mental health and emotional precarity, as is readily apparent in the work emerging this year.

And as for experimental exhibition formats, the new norm appears to lean as heavily into multimedia to tell stories about objects, as the objects themselves. Melbourne’s Katie Britchford, curates an exhibition of films about jewellery, in response to long-held frustrations with the sameness of shows of the past. 2020 offered the perfect opportunity to showcase film as an alternative, while elegantly giving space to artists with multi-disciplinary practices, of which jewellery is just one aspect.

Similarly, the collective Norwegian Association of Jewellery Designers, have expanded their practice since the pandemic led them to produce digital installations, and like many, found the result so compelling that they’ve embraced a multimedia approach to exhibition making. In Atlantis, they created not only jewellery, but a collective photoshoot and a short film as well. Producer Aliona Pazdniakova shares that this method “creates a context and a stage for all the works to co-exist organically inside one narrative.”

This sentiment is echoed by many, including Luisa Kuschel, current artist-in-residence at Marzee’s Intro gallery in Amsterdam, who relates that she found the act of photographing her work The Beaded Confinement, as important to the object as the making itself. The process of documenting a series of human-scale slave chains, allowed her to create a narrative around the work through a context over which she herself had control, and rendering the photographs artworks in their own right.

In many ways, Schmuck + Munich Jewellery Week is a phenomenon that continues to hold up a mirror for the field of contemporary jewellery, in its evolution and history. Growing as the field grows, it’s an extension of the dynamics and prerogatives of everyone involved, and under the best of circumstances, a resource we ourselves can shape.

Plus, in Peter Bauhuis simple yet poignant take, ‘The reason so many people come to Munich, is because so many people are coming to Munich.’ So here’s to Munich, especially this Summer.

This material was published on the occasion of Munich Jewellery Week 2022.

You can experience this piece in print by purchasing the Munich Jewellery Week official publication here.