In this essay, I will discuss the role of crafts in an ‘entangled world’, highlighting artists who pursue situated practices with long-term attitudes and commitments to nature, material sources and the histories that belong to specific places. Craft is a practice that is based on responsiveness, on the ability of response (response-ability) to traditions, to urgent questions, to materials, to technology, to others – both human and nonhuman – that are interconnected, bound together and entangled in the process and experience of making something. Today, due to the climate crisis and an unsustainable anthropocentric worldview, we are urged to look closer at crafts as practices that are situated and responsive to complexity. The definition, perception and utility of contemporary crafts are being re-discussed and re-considered at a time and in a world that is profoundly disrupted by the actions and choices of humans.

Making as an epistemological practice is profoundly entangled with a complex world system. This becomes especially clear if we think about the ways that making and craft practices are rooted in traditions, communities, histories and cosmologies, and how they are connected to a sense of place and to access to material resources (or the lack thereof). This way of knowing requires multiple responses from different perspectives – both human and nonhuman.

According to the feminist theorist Karen Barad, ‘knowing is a distributed practice that includes the larger material arrangement. To the extent that humans participate in scientific or other practices of knowing, they do so as part of the larger material configuration of the world and its ongoing open-ended articulation’ (1). Barad argues that ‘it is not an ideational affair or a capacity that is the exclusive birth right of the human’, nor is it ‘a play of ideas within the mind of a Cartesian subject that stands outside the physical world the subject seeks to know’. Rather, ‘knowing is a material practice, a specific engagement of the world where part of the world becomes differentially intelligible to another part of the world’ (2). This way of knowing demands specificity and difference, and these in turn require that we learn to see from another position and point of view than those to which we are accustomed. In this sense, making and crafting become responsive to a particular situation, accessible via experiential learning across individual practices with distinct embodied cultures. When we as makers are able to situate our practice in a specific context or environment, and to respond to it in dialogue with others and across differences, then interconnected actions and behaviours become visible and can enable us to understand the world, especially in its present disrupted state.

We who live in the developed world have a globalised culture unhindered by geographical boundaries. But this perspective demands to be reconsidered. If we look closely at the urgencies of our time, particularly human-caused phenomena such as climate change and the mass extinction of species, there is a necessity for craft practitioners to reassess their materials, processes and actions – especially in today’s information and internet age, where resources seem unlimited and everything is just one click away. The times we are in require us to rethink our roles, methods and responsibilities as craft practitioners, and to understand how our own actions and choices affect the world around us. One way forward is to uncover and make room for perspectives that are too often overlooked by an anthropocentric worldview.

Situated Practice

The works by Hildur Bjarnadóttir, Britta Marakatt-Labba, Riitta Ikonen and Karoline Hjorth that are included in the exhibition Earth, Wind, Fire, Water are about, and engage with, specific places and a sense of belonging. These artists are deeply concerned with the relationship between humans and nature, and with the potential of reconsidering this relationship in a world that is interconnected and disrupted by human-caused phenomena, that is, in a world where it is no longer possible to think in terms of opposites or dichotomies (e.g., human-nonhuman, craft-industry, object-subject, nature-culture). Their artistic practices attempt to understand crafting and making as processes that go beyond their studios’ walls, and as ways of knowing that do not belong exclusively to self-reflective and self-reliant endeavours. Through their work, the artists establish a dialogue that is sympoietic (3).

This kind of dialogue is with multiple others, both human and non-human, and embraces situ ated practices within local entities and habitats, while at the same time addressing social and global environmental concerns. The works of both Ikonen and Hjorth, and of Bjarnadóttir, become site-responsive by engaging with a specific place and its inhabitants in a way that is ongoing and recursive. They therefore suggest that contemporary crafts not only exist in a traditional studio craft context but are entangled with the environment on a local and global scale, and with society in all its complexity.

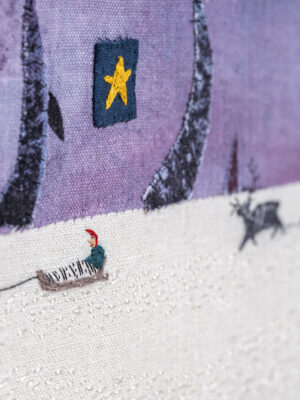

As the poignant embroidery and appliqué works of artist Britta Marakatt-Labba remind us, a sense of place is related to a person’s history with a certain place and their roots – it entails personal and collective memories and an understanding of how a community, animals, things, materials and memories are interconnected. Marakatt-Labba refers to motifs from Sámi history and mythology; her work often converges with her upbringing in a reindeer herding family on the Swedish side of Sápmi, and with a dialogue interwoven between past and present and between duodji (craft) and dáidda (art). Duodji in Sámi culture has a deep meaning and is intimately related to the flow of material, people and their surroundings.

Traditionally, craft has been related to a sense of place – its local history, people and experiential knowledge of a place. Locally produced objects, for instance marble objects from Carrara or glass from Murano, typically thrived economically and aesthetically, even becoming forms of currency and coveted goods to trade and exchange, thanks to the resources within a given territory. If we look at the first prehistoric examples of flint knapping – stone tools used by early humans that were systematically shaped with other stones by hand – archaeologists are able to trace the material origin by examining physical properties (colours, signs, and facets) and by measuring the symmetrical marks along the axis from thin to thick and from front to back. In this way, we begin to see a tooling knowledge unfold: from stone axes to hand tools, to ornaments and weapons. Material origin has contributed to creating a value system whereby a material originating from a specific geographical area has been invested with particular meaning, associations and functions. Today, as an effect of a globalised world and of industrial capitalism, it has become harder to connect with how things are made, understand where they come from, how materials are extracted and processed, by whom and at what cost. Material flows have become more opaque and harder to grasp. Furthermore, irreversible man-made climate disruption, overproduction, overconsumption, and widespread pollution affect our relationship with things and how we make. It is now essential, for us as makers and craft practitioners, to look closely at our own positions of responsibility in a complex world system. Hence, by situating our practices in a disrupted and complex world, we can gain a new understanding of materials, resources and processes, their impact and significance to other people, communities, species and natural environments.

Ecologist Eugene Stoermer and Nobel laureate atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen coined the term ‘Anthropocene’ in 2000. They initially used it in the context of geology, referring to the influence of human behaviour on the earth and how it has irreversibly affected, over time, our planet’s atmosphere, lithosphere and hydrosphere (4). The term has gained momentum and is today widely and informally used by scholars, craft practitioners, journalists and broadcasters – also across fields of knowledge, from the arts and sciences to the humanities, politics, and more – to identify a proposed new geological epoch in the Earth’s history, subsequent to the Holocene epoch. Today the term has gained popularity and appeals to a cross-disciplinary discourse, from the arts to the sciences. In her 2016 book Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, scholar Donna Haraway discusses in depth her issues with, and criticism of, the term Anthropocene, and how a different word, ‘Chthulucene’ (5), might be better suited to an epoch of resurgence – a time of learning how ‘to stay with the trouble of living and dying in response-ability on a damaged earth’ (6).

Her criticism has in part to do with the very root of the word Anthropocene: anthropos. Haraway posits that ‘a number of experts think of anthropos as the “one who looks up from the earth,” the one who is earth-bound, of the earth, but looking up, fleeing the elemental and abyssal forces, “astralized” (7). But if we want to change the story and learn how to live on a planet that is irreversibly disrupted by the effects of industrial capitalism, then we have to look closely at, and tell stories about, things that are earth-bound. Anthropologist Bruno Latour argues in a similar vein, especially now, in this catastrophic time of the Anthropocene, when what ‘used to be called nature has erupted into ordinary human affairs, and vice versa, in such a way and with such permanence as to change fundamentally means and prospects for going on, including going on at all’ (8).

In this sense, it is important to consider how contemporary craft practices can respond to and engage with such an urgent and complex problem. In particular, how can we, as craft practitioners of this timescape, reflect and react in symbiosis with the Earth, to find solutions with craft knowledge that lead to fundamental changes in our relationship with the Anthropocene?

What we call nature has often been taken for granted and considered largely available; it is now being depleted, and spatial settings, from local neighbourhoods to faraway places, are being disrupted by current extractive modes of resource management, from soil depletion to industrial mining, oil drilling and marine industrialisation. These phenomena are considered hyperobjects (9): all-encompassing and distributed so vastly both in time and space, that they have affected most layers of the Earth, as well as human and nonhuman bodies (10). Thus, what we today understand as ‘local’, or what we associate with a specific sense of place, is likely a reality profoundly affected by these phenomena. Hildur Bjarnadóttir engages with questions related to hyperobjects through on-site engagement, by re-activating local land and eco-systems, re-defining roles and dyeing methods essential to her artistic research. Central to her research is the question of how a place or a sense of belonging can affect the artist’s knowledge in relation to questions of ecological destruction, and how one can eventually become site-responsive and cultivate responsibilities.

Stressing the importance of ‘staying with the trouble’ of a damaged planet that is not yet murdered (11), Haraway suggests how the only way to do so is through ‘generative joy, terror, and collective thinking’ (12). She points to the necessity to pull on a thread and begin to untangle the ball of meanings, and begin to trace through one thread and then another, to find tangles and patterns crucial to staying with the trouble in real and particular places and times at a particular moment in history for a particular group of people. She speaks of string-figuring (13) – in all of this, the goal is not to fix a problem or restore anything, for there is no way to go back to

any ideal ‘before’. A ‘game-over attitude’, waiting for the end of the world, is no solution either. What is possible, though, is to come together, to make together, to engage with each other in ‘unexpected collaborations and combinations’ (14) for a resurgent world.

Inspired by the experience and memory of her grandmother, who owned and tended to her own land, Bjarnadóttir acquired a piece of land called Þúfugarðar in 2012. This led the artist to re-connect with the land, as she made Þúfugarðar her home as well as studio. Most of the materials Bjarnadóttir has used in her textile works are self-harvested: from the wool she has collected from her flock of sheep to the dyes used in Colors of Adaption, her installation at Galleri F 15; the pigments for the dyes were in fact sourced in the summers of 2015 and 2016 from plants that the artist grew herself in Þúfugarðar. Bjarnadóttir’s materials are thus intimately connected with the land, its memories and histories, and its plants, soil, air, root systems and ever-changing weather conditions affected by the hyperobject that is climate change. Bjarnadóttir, through her practice, responds to, and engages with, her local milieu in Iceland. One of her early examples is her exhibition Flora of Weeds, which involved transforming a church’s entrance hall into a greenhouse. During the exhibition period, which lasted for two winter months in Reykjavik, she grew several species of weeds whose seeds she had collected from the neighbourhood surrounding the church. As Bjarnadóttir points out: ‘I wanted to explore the church community’s potential to talk about rootedness, up-rootedness and displacement. Choosing weeds for this exhibition speaks about hierarchy and categorisation outside and inside the church. Many weeds are not considered Icelandic, even after being here for over 60 years.’ (15) For her latest work at Galleri F 15, Colors of Adaption, Bjarnadóttir continues to investigate related issues of belonging, rootedness and ecological disruption through her artistic interventions, thus decentralising humans in relation to other beings and understanding nature not as a resource but as a symbiotic collaborator.

Making Together With

Anthropologist Anna Tsing has termed our existence as an ‘interspecies relationship’: we cannot exist without microbes, spores and the multi-species landscapes in which we live (16). Craft as a material practice, through the making and thinking processes that are at its base, has the potential to enable us to understand our own positions of responsibility in a complex world system and to become a tool for re-telling stories. In this sense, craft is a useful tool to reveal what is unnoticed. It helps us to see through what we thought we knew – to find a new way of understanding our world – by enabling us to observe how things are entangled. The qualities of a textile piece – as the works of Bjarnadóttir and Marakatt-Labba attest – render us able to understand how there is no separation between nature and culture, how things are surrounding us and how we surround them, how we are all interconnected in a sympoietic process. According to Haraway, ‘Sympoiesis is a simple word; it means “making-with”. Nothing makes itself; nothing is really autopoietic or self-organizing.

[…] Sympoiesis is a word proper to complex, dynamic, responsive, situated, historical systems. It is a word for worlding with, in company. Sympoiesis enfolds autopoiesis and generatively unfurls and extends it.’ (17). Care and responsiveness are important aspects in Marakatt-Labba’s work, as the artist is able to respond to the physical qualities of her material – a fold, a shadow, or visible line in the fabric – to evoke and relay through embroidery the stories of the land and its people. Care and responsiveness are present in Bjarnadóttir’s practice too: the artist situated herself in a specific time and place, tended the land where she harvested her plants that she grew, eventually using them as sources of pigment for her plant-dyed silk tapestries. She responded to the site and to its inhabitants, in an ongoing and unexpected collaboration, adapting her own methods and making together with plants, soil, sheep, air and weather conditions through her artistic interventions – this represents an integrated axis of care with a specific landscape. It reflects a long-term attitude that extends beyond the physical space of the studio to directly engage with a site, its materials, memories, histories and manifold actors and species.

Infrastructural development and technological progress have increased individuals’ accessibility to different places and affected our preferred modes of communication. As I write this text, the world is experiencing the COVID-19 virus.(18) Its spread through global air-routes raises new and urgent questions about globalisation, as we become aware of how much we have taken for granted: travel, accessibility to far-flung places and material resources, and the possibility to gather together, to make, and even to exhibit and share art. At the same time, NASA has been monitoring how the air-travel block to and from China has contributed to a significant drop in air pollution in the country: satellite images show a drastic clearing across the skies of China. The effects of the COVID-19 virus reveal how vulnerable we are as well as how the world and its biosphere are vulnerable because of how related and interconnected humans and non-humans are. This is an essential and ethical realisation that can lead to empathy and the cultivation of responsibility.

By ‘making together with’ and by responding to manifold entities, an ethos is developed towards daily processes of care that manifest an intimate relationship to resources, materials, places and human and nonhuman others. This ethos is evoked in the works of many of the artists included in the exhibition, not least in the collaboration of the Norwegian-Finnish artist duo Karoline Hjorth and Riitta Ikonen. Since 2011, they have photographed more than 100 seniors, presenting them as immersed in their natural environment, wearing sculptures made of natural materials from their surroundings. The seniors have sometimes also worked with Hjorth and Ikonen to make the wearable sculptures. In the photographs, human-nature-material appear to grow together, to become inseparable from each other. Hjorth and Ikonen’s practice is mobile and flexible, and it is capable of inhabiting diverse local realms: the artists travel near and far away, from Norway to Japan, in order to carry out their project, and their project is adapted to many contexts. Each particular visual story reveals local qualities and raises specific questions on each occasion. Hjorth and Ikonen’s involvement with the countries they travel to (a practice that may be not sustainable in the long term) and their engagement with the stories of the people who inhabit these places represents a different approach than Bjarnadóttir’s, for her work is rooted in one particular place (Þúfugarðar). Furthermore, her processes are more time-consuming, dependent as they are on peculiar collaborators, starting from the plants grown by the artist herself. Yet Bjarnadóttir, Hjorth and Ikonen all work on-site and often need to respond to a particular and unfamiliar situation, as their studio space coincides with the site in which they immerse themselves. Not relying on a defined studio situation and on the comfort of specific sets of tools, materials and techniques that they are familiar with allows these artists to question and challenge themselves and their knowledge, together with and in a dialectic relation to others, both human and non-human. And especially through situated learning and making with others in their chosen contexts, they seek a new sense of place, of belonging with nature, and a response-able way of being in the world.

Craft as a practice is related to a multitude of histories, disciplines and ways of learning and making. By being situated in a site or context beyond the familiar studio setting, possibilities to understand vulnerability – our own as well as that of the sites and actors we work together with – are opened up, and we begin to understand interconnectedness. At the same time, we are confronted with norms and habits that we have come to internalise and sustain. Situated practices, making together with others, establishing ongoing dialogues with specific sites and collaborators, are all ways of knowing that enable us to understand our own positions of responsibility in a complex world system: the ways our actions and choices affect the world around us. Hence a new understanding of materials emerges, as well as of resources and processes, their impact on others and their significance for individual people, communities, species and natural environments. This understanding in turn offers the possibility of rethinking and reconfiguring our practices as makers and craft artists.

Bibliography

1

Karen Barad,

Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 379.

2

Ibid., 342.

3

The adjective ‘sympoietic’ pertains to the noun sympoiesis. From Ancient Greek, σύν (sún, ‘together’) and ποίησις (poíēsis, ‘an act or process of making’). See also Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble, Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham and London:Duke University Press, 2016), 99.

4

For a more in-depth history of the term and its use, see Will Steffen, Jacques Grinevald, Paul Crutzen and John McNeill, ‘The Anthropocene: Conceptual and Historical

Perspectives’, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, vol. 369, issue 1938 (January 2011), 842–867.

5

Chthulucene, from the Greek term chthon, meaning ‘earth’, is an era of resurgence proposed by Donna Haraway. She proposes it as an alternative to Anthropocene, which is already an accepted definition of the present era, characterised by irreversible anthropogenic changes on the Earth. Chthulucene is

associated with critters and things that dwell in or under the earth. See Haraway, Staying with the Trouble.

6

Haraway, Staying with the Trouble, 2.

7, 8

From the interview ‘Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene: Donna Haraway in Conversation with Martha Kenney’, 223.

https://lasophielle.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/ab1cd-artanthro_haraway_proof.pdf

9

Ecological theorist Timothy Morton frames global warming as a ‘hyperobject’, that is, an object that occurs over time and exists on a scale that is too large for human perception.

Such an immense scale causes problems for humanity in seeking an ethical response, because only the symptoms of the problem can be observed, and not the thing itself. For more context, see Timothy Morton, Ecology without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009).

10

Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

11, 12 Haraway,

Staying with the Trouble, 31.

13

For Donna Haraway, the term string-figuring refers to two string-figure games: one Indigenous Navajo game (na’atl’o’) and the other, a non-Indigenous (cat’s cradle).

14

Haraway,

Staying with the Trouble, 4.

15

Hildur Bjarnadóttir, ‘Textiles in the Extended Field of Painting’ (Fellowship Thesis, Bergen Academy of Art and Design, 2016), 69.

16

Anna Tsing, ‘Unruly Edges: Mushrooms as Companion Species’, Enviromental Humanities 1 (1 November 2012), 144.

17

Haraway, Staying with the Trouble, 31.

18

Coronavirus disease 2019, a disease related

to the SARS virus.

About the exhibition and publication:

The anthology Earth, Wind, Fire, Water accompanies the exhibition by the same name at Galleri F 15 in Moss, Norway. The exhibition Earth, Wind, Fire, Water – Nordic Contemporary Crafts is the 44th edition of the series Tendenser (“Tendencies”). For nearly fifty years, Tendenser has been one of the leading platforms for contemporary craft in the Nordic region. First presented in 1971 as an annual exhibition highlighting Norwegian practitioners, Tendenser has since expanded to a biennial format, incorporating trends from across the Nordic countries. Former curators of the exhibition include Glenn Adamson, Jorunn Veiteberg, Lars Sture and Stephen Knott.

This year’s exhibition is curated by Randi Grov Berger and brings together seventeen artists and artist groups from the Nordic countries who uses their craft, their tools, and their deep material knowledge to address pending environmental issues. Acknowledging the powerful interdependence between humankind and often overlooked materials and organisms, many of the presented artworks evoke the fragility and transiency of our earthly existence by way of components that alter, dry up, or decay throughout the exhibition period.

The publication Earth, Wind, Fire, Water is an anthology that brings together seven distinguished writers and thinkers living in the Nordic region: Camilla Groth, a ceramic artist, teacher and post doc researcher at the University of Gothenburg; the curator and writer Jenni Nurmenniemi; Nicolas Cheng, a jewellery artist and researcher; Jessica Hemmings, an author who writes about textiles and a professor of craft at the University of Gothenburg; Nina Wöhlk, a freelance curator and writer; the poet and translator Ánne Márjá Guttorm Graven; and Æsa Sigurjónsdóttir, a curator, writer and associate professor at the University of Iceland. The texts in this publication are written in several Nordic languages in addition to English.

The exhibition serves as a backdrop and inspiration for the writers as they forage deep into the material world and endeavour to flesh out concepts such as material interaction and material agency, Posthumanism, site-responsiveness and symbiotic thinking. How do artists relate to their chosen materials? What does a human-material interaction look like, and how might one approach a material, not from the position of a master, but from that of a collaborator?

Team:

Editors: Randi Grov Berger & Tonje Kjellevold

Contributors: Nicolas Cheng, Camilla Groth, Ánne Márjá Guttorm Graven, Jessica Hemmings, Jenni Nurmenniemi, Æsa Sigurjónsdóttir and Nina Wöhlk

Press contact: Johanne Nordby Wernö / St. Hans Kommunikasjon

Graphic design: BLANK BLANK

The publication is a collaboration between Galleri F 15 and the Nordic Network of Crafts Associations and is supported by Nordic Culture Fund and Nordic Culture Point.