As a Tokyo resident for over 30 years, sometimes I get bored with my repetitive daily life but never with the city itself. I owe this to the Tokyoites and people from all over who are pulled in by its magically strong magnetism. They never cease to show you the unexpected.

Tokyo is also a magnet for artists looking for inspiration and success. By focusing in on a few different areas we might be able to discover why: the major fashion epicenter of Shibuya where several cultural educational institutions are located is one area ne of them a jewellery school that shows how the diversity of the city fuels its lecturers and students. We’ll also take a glimpse at the creative practices of a handful of other diverse artists scattered throughout the city. Some are modern, while some are nostalgic—a sentiment that seems a world apart from Tokyo’s mutable city streets.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

The day begins near my home in Kokubunji, a residential area flush with nature in the center of Tokyo’s concrete jungle. A 30-minute train ride east brought me to Harajuku station. As I got off the Yamanote loop line I was joined by a notably younger crowd that includes a few fashion freaks in designer clothes. The crowd pushed me along the short trip from platform to exit. I met my photographer and veered onto Omotesando and its rows of zelkoya trees, then turned left onto another main street, Meiji-dori, lined with stores of vibrant colors and eccentrically-shaped buildings plated in glass. We were heading towards the Aoyama campus of Hiko Mizuno College of Jewelry.

The school was established around 50 years ago as a private gem polishing school for hobbyists. It has since grown to include an Osaka campus and three satellite buildings in Shibuya for its watchmaking, shoemaking and bag making departments.

‘Did we step into the wrong room? Aren’t these supposed to be jewellery students?’

We passed through the main gate into a court and were greeted by large buildings on all sides. We entered and rode the elevator to the first floor that displayed work by Otto Künzli, a Swiss jewellery artist, behind a glass wall. This was a classroom for third year students of the Fashion Art Accessory (FAA) Major. The adjoining room was for Institute students. There was no wall between the two rooms. While the FAA course prepares students to pursue either art jewellery or fashion jewellery, the Institute is focused on branding and curation and is open to graduates from the three other creative departments.

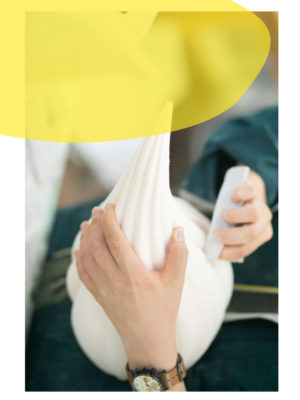

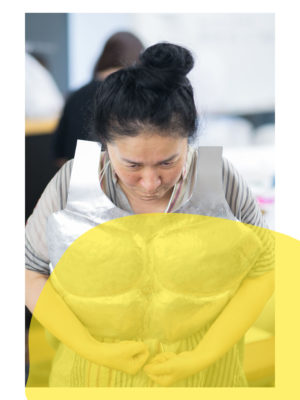

We walked into the room and met a sight far different from what I had imagined from a jewellery school: there was a female student struggling with large masses of white Styrofoam, a workbench piled with pastel-colored cotton, sewing mannequins wearing work-in-progress pieces… questions popped into my mind one after another: Did we step into the wrong room? Aren’t these supposed to be jewellery students? What are they working on in the first place?

I found Mikiko Minewaki, FAA head and jewellery artist, sitting at a desk near one of the doorways. Mikiko is a popular lecturer. According to her, the students were preparing for an accessory show coming the month after next. During our short photo session she was bombarded with comments from students. One was having trouble getting resin to harden, while another was hammering a large sheet of metal into six-pack abs.

‘I think jewellery can’t come from studying only jewellery.’

If one couldn’t tell from the lineup of odd materials, FAA asks students to reexamine their preconceptions to enable them to see all objects as possible materials on par with precious metals like silver and gold. Mikiko said, ‘Spending your life on the lookout for the perfect materials primes your mind to discover creative methods and have fun in general. It’s a lifestyle, really. Rather than aim to create skilled or amazing items, I want my students to share the joy of discovery.’

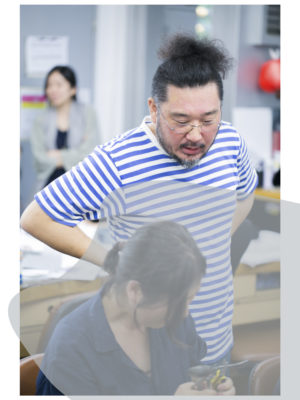

The scene in the classroom backed up her words, and the lively room was full of joy. I looked up to see Ryo Saito, the Institute head, being asked by a student to try on a work-in-progress piece. He put it around his neck and began to vogue around the room much to the amusement of the small group around him.

Ryo doesn’t have a background in jewellery. Originally he worked as a designer and made installations and movies. His career as a jewellery artist started only after he began lecturing at Hiko Mizuno. When asked about his position as a teacher he explained, ‘I think jewellery can’t come from studying only jewellery. To create something new you need to utilize what you learned from other fields, be it manga, literature, movies or art. Sticking to the standards of a certain field makes you blind to boundaries that are obvious to outsiders. Jewellery isn’t even my most subject. I think there’s value in having teachers from non-jewellery disciplines.’

Ryo has presented this value not only through teaching but also through his work at a campus gallery called Hole in the Wall. It was here that he showcased his installation that incorporated a short film, a slight twist on the gallery’s jewellery-dominated formula.

We went downstairs to see what it was all about. As we stepped inside I was struck by how bright the room was compared to the cloudy sky outside. A large piece of translucent cloth hung in the middle of the gallery, flapping as the wind blew through one door to another. Our visit coincided with a solo show the bag artist, Yusuke Kagari. Several pedestrians came in for a closer look, intrigued by the rows of various leather products visible from a square window along the street. Hole in the Wall is open for the public to enjoy the works of students and graduates along with domestic and international artists and designers. Located to the left of the school’s gate, the space works like a tunnel that connects the school and street.

This campus gallery is not the only chance for the public to take a glimpse of the growing talent of the students. There is also the annual graduation show, a spectacular collection of works from the jewellery, bag making and shoemaking departments. I was reminded of the last show that took place at a corridor gallery in a large modern building on Aoyama-dori, one of Shibuya’s main streets.

As I walked along a straight hallway, several panels of large pictures and objects caught my attention. The extravagant juxtaposition made me wonder to which department the maker belonged. As I got closer I realized they must have been created by a jewellery major as I noticed a familiar, beaming smile in front of the work. It belonged to Yasuyo Hida. She graduated from Hiko Mizuno last March from the Institute with a major in FAA. As a student she set out to become a professional jewellery artist and last October she had her solo show entitled Emotion in Monochrome. It featured jewellery, video, photograph and a display of growing crystalline structures for a multifaceted range of mediums and materials: organ-shaped plastic toys incorporated into bizarre ear pieces, spine-like body ornamentation made of flour, a painted Noh mask hanging from the wall.

Our conversation was brief but it was enough to learn various aspects of her character. When asked about her source of inspiration, she named a Japanese stylist rather than jewellers or contemporary artists. She had studied sewing techniques at a fashion college after leaving her science major. Her background was surprising but convincing givenhow skillfully she incorporates fashion into jewellery.

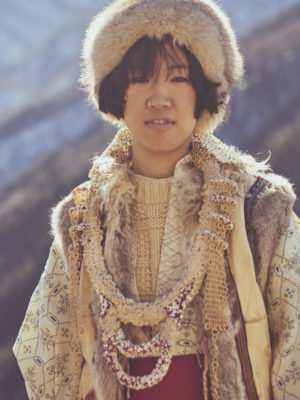

Reviewing her graduation works I found pictures a boy and girl on a snowy mountain. The large wearable objects in the photo added an exotic touch but there was something more. On closer inspection I found that the pieces were covered in a dense, grainy texture, a detail that set the ethnic costumes apart from any I’d ever seen. Yasuyo explained that the bizarre texture was created with a foaming binder, a material usually used in silkscreen printing. While attempting to recreate a crystalline structure from a previous work she hit upon the perfect material.

These works were set against a backdrop depicting the countryside. A forest during the winter thaw dotted with wooden sheds surrounded by wood fencing; hers s an archetypical nostalgic landscape of rural Japan. Maybe that why the imagery felt familiar.

On the other hand, for someone who grew up in Tokyo, the city of manmade objects, even an artificial cityscape can be a source of nostalgia. Another emerging jewellery artist, Saika Matsuda, uses this idea. She graduated from Hiko Mizuno in 2015 and now studies at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts. A strange mix of contradicting inspirations make what she does utterly unforgettable. I still remember the moment I first saw her works; it was in the twilight of an open-air exhibit, and her pieces stood out due to their brightly colored bizarre shapes that were menacingly large by jewellery standards. I felt uncomfortable yet completely captivated by their strong presence.

To better understand her work, we need to turn our gaze back to downtown Tokyo.

Have you ever wandered the back alleys of Tokyo’s cultural epicenters in Shibuya or Shinjuku? You may be overwhelmed by the flood of distasteful colors and flashy lights from electric signs outside pachinko parlors and sex shops. If you’re not careful as you walk by, the blast of noise and rank cigarette smoke that shoot through the automatic doors of pachinko parlors will knock you off your feet. Saika finds this scenery disturbing but visually intriguing and tries to incorporate it into her jewellery. To neutralize the negative image, she looks to something positive, even celebratory– raditional Japanese lucky charms and family crests—while using dollar store trinkets as the main materials.

Saika said her affection for the unsettling is rooted in her hometown. As the largest planned city in Japan, it was already past its prime when Saika lived there in the 90s. As she describes, ‘It saddens me that this once ideal residence for happy families has become insignificant. Seeing the town deviate from its original purpose makes me uncomfortable. It’s scarily similar to an abandoned ruin. These feelings stuck with me and are now nostalgic in a way.’ There’s no trace of nature in the colors, materials or forms in Saika’s works—which makes sense for an artist raised in one of Tokyo’s many artificial cities. The resulting nostalgia is likewise artificial, but real all the same.

Saika is not the only artist who turns to objects to create art pieces The artist duo known as Magma, similarly develops unique works. Their practice exemplifies how a strong attraction toward objects can deliver an exhilarating rush of the familiar that can transform even unsightly junk into an object of desire.

Their nearly 40 commissioned projects cover everything from the large-scale—interior design for fashion brands, music videos and commercials and art direction for magazine shoots—to the small-scale, such as branded accessories. In 2015 and 2016, they were busy with solo shows.

Their studio is located in Tachikawa city in western Tokyo. This hub city of the rural Tama district has more shops and office buildings than the surrounding stations. It feels as crowded as central Tokyo but after 15 minutes on the bus, the hectic stage is replaced with rural scenery of housing complexes, sweeping fields and forests. As the bus neared our final stop it went past a large, two-story structure that looked like a coop built on top of a warehouse or storefront. I knew we were in the right place when I saw the fluorescent crates stacked around the back. The flashy crates were out of place amidst the colorless rural landscape but they fit my reference materials for today’s interview. The aluminum sliding doors were too plain for a main entrance but out stepped Jun Sugiyama, one half of this artist duo.

Magma was formed in 2008 by Jun Sugiyama and Kenichi Miyazawa, two friends from Musashino Art University who were born in 1984. They create one-off art pieces and even take commissions. Their unique mix of nostalgia and innovation has a dedicated fan base and their products sell out online relatively quickly.

As we entered their ground floor studio we were welcomed by an overwhelming amount of, for lack of a better word, things. Wood blocks, squared timber and other materials, ready-made articles including plastic figures of anime characters, a frame for a retro cigarette kiosk, pieces of furniture and toys. Magma draws inspiration from everyday items. In their studio, peeling paint and sun bleaching becomes an artistic flourish.

Our conversation started in a corner of their storeroom that doubles as a workspace. It was just past 2:00 p.m. but the room was dim due to the sparse windows and cloudy weather. Kenichi gestured at a tall lamp shaped like a yellow pencil and said, ‘Our process starts with an object like this. We don’t make things from scratch so we need for materials to fall into our lap. But we don’t bother with things that look perfect out of the box. What we want is something unattractive, incomplete.’

While their colorful products are loud and direct, the two artists quiet and thoughtful in answering our questions. And they became all smiles and excitement when the topic turned to their creative process. Their serious attitude towards crafting was clear from how carefully they poured over the pages of past issues of CO I had brought for their reference. Of course, Jun couldn’t deny his attraction to objectssomething he considers a defining quality of Magma. He chalks up the quirk to ‘a generational thing.’ Kenichi owes his passion for objects to his parents. According to him, his father held onto everything including paper bags and you can easily see this nature running through his blood, too.

Tokyo: a city where the new replaces the old in a blink of the eye. This new, vibrant nostalgia seems to reveal itself in the output of all these talented artists who call Tokyo home. They have made the city’s superficial material culture a part of their own identities, transforming the memories and emotions associated with its artificial landscape and objects into captivating pieces of art. Their work shows that even a mutable city can create a sense of longing for the things it leaves behind.

As he continued to talk, I was surprised how each story was so closely associated with an object: the electric fan and kotatsu table from his parents home, automobiles, like something an anime hero would drive, that he found at the studio he used to work at, and on and on. He showed me these objects through vivid descriptions that made me understand why he ended up as an artist.

On the other hand, Jun went to an art university because he liked fashion and wanted to make clothes. There he also learned about stage props and furniture making. However, working with wood and plastic made him want to branch out to create anything possible. He cited the Berlin and Paris-based BLESS as a major influence. BLESS also work as a pair: one has a background in architecture, the other fashion, and both skills help them to produce furniture. Remembering them Jun said, ‘I wasn’t aware of it at the time, but looking back, they inspired me to set my goals beyond fashion.’

Magma’s explosive creativity propels their art across conventional boundaries and now they have their eyes set beyond the borders of Japan.

Tokyo: a city where the new replaces the old in a blink of the eye. This new, vibrant nostalgia seems to reveal itself in the output of all these talented artists who call Tokyo home. They have made the city’s superficial material culture a part of their own identities, transforming the memories and emotions associated with its artificial landscape and objects captivating pieces of art. Their work shows that even a mutable city can create a sense of longing for the things it leaved behind.

Makiko Akiyama

Writer and translator. Born in 1979 in Osaka, Japa. In 2013 launched a newsletter for Japanese readers featuring translated articles about art jewellery. Contributing writer for various jewellery and craft publications.

This article was first published in #5 Vernacular Current Obsession Magazine, 2016. You can order the issue here