Current Obsession: You mentioned that at the moment you’re sitting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow where you’re currently teaching. Could you tell us how that came about?

Justyna Górowska: It happened after living for a short time in the United States where I met my husband and got married. We decided to go back to Poland because I was graduating with my PhD at the Poznan University of Arts. Unfortunately, covid started and we were stuck here in Krakow. I got the proposition to teach at the Academy and I accepted it. I think I made this decision for two reasons. One reason is that I was quite tired after years of freelancing and traveling, doing residences, exhibitions, and my economical situation was also not very stable because of that. So teaching at the university has given me the chance to feel a little bit more secure. The second reason is because many of my projects are very socially and community involved. I really like to share my knowledge and skills with the students and I also feel like this is my social involvement.

CO: Is your background in performance art?

JG: I graduated from the same Intermedia Department that I’m teaching at now. Intermedia is a historical term that came from one of the founders of the Fluxus Group from the 60s, Dick Higgins. Intermediality is the combination of means of expressions, that are characteristic of various disciplines, in one artistic realisation; using materials and methods associated with various artistic fields.

That’s why at our department you can go really into tech, software and emerging technologies; but then you also have the performance art, which is very body based practice. I found this term very accurate for my art practice. But now I think that we are living in even more Postmedia reality. It’s very difficult to say what is performance, what is video art, what’s interactive installation anymore? Because each media influence each other and merge into forms never recognised before.

CO: How do you find that in your art practice?

JG: This Department made me who I am and what my practice is. That’s why I’m very into working with my body while utilising new technologies where a critical point of view is very important to me. What I’m really into in my art practice is the perspective on living in the world with so many crises, like social, political, ecological. That was also the idea of Higgins, who believed that all classifications are not needed and Intermedia are cultural models leading to democratic society.

I think that all the people I’m working with are people who are very socially involved and they believe that through our activities we can change the reality that we’re living in.

CO: Since you use such a wide range of media in your work, I was just wondering do you collaborate with others to create your desired outcomes or do you work independently?

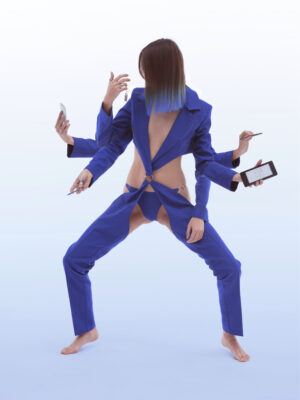

JG: I love to work with people and even if I’m doing “individual” work, there are some people involved in the process. I have the experience of working with fashion designers. I did a couple projects in cooperation with polish designers Pat Guzik (“What You Don’t Know, Can’t Hurt You“ 2018 ) and Marta Kołtun (“Cyber Wedding to the Brine Shrimp”, 2021). I did some collaborative performances with other artists like Zeynab Gueye (“Nymp Tears”, 2022) or non-models from New Aliens Agency (“69”, 2018).

I am also member of Nerdka Collective, a cyber feminist group with whom I did some interdisciplinary projects (like perevirka.com). Above all I love to work with artists, educators and scientists in collaborative projects that show deep concern about water. I’m taking part in two projects which are based in Krakow. The Flow, a Summer residency on the boat, on the Vistula river, where we’re continuing the tradition of Polish timber rafting (polish “flis” ) and appreciating it together. I’m involved in another group called Sister Rivers, where each of us represent different rivers by using plates with river names during happenings in the form of protests.

CO: How do you come across these collaborations?

JG: Because of the common interest. I think that all the people I’m working with are people who are very socially involved and they believe that through our activities we can change the reality that we’re living in. Many of the people are the people who are looking for social justice within the queer or ethnic communities or climate justice. So yeah, I would say this is the common point for those collaborations.

CO: Where does this interest come from?

JG: I think what really inspired me was the posthuman theory that I was reading a lot during my studies, especially in the context of interspecies relations. I started doing this project where I was involving pets, like my parents’ dogs and cats, where I was exploring the border between human and non-humans beings. In my research I found out there is a gen–FoxP2–and its human mutation allows us to communicate through language; I believe this has distinguished us so much from other animals. For an experiment in cooperation with a biotech lab, we were able to extract this gen from my blood.

CO: In relation to that, I have a question about one of your works where you married a Brine Shrimp. And I was just wondering if you can tell us more about this marriage? Do you view the Earth as a lover?

JG: I was writing my PhD about performative incarnations in the water nymph @wetmewild, where I was questioning if the ancient Slavic goddess could survive in the contaminated rivers in modern times. Following the myth where she was known for her seductive powers, I started using erotica as a tool while sneaking educational information about water conditions.

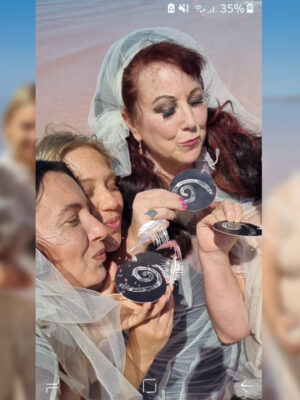

Through my research, I found this ecosexual movement established by Annie Sprinkle and Beth Stephens that become big part of my PhD thesis because of this mixture of sex and ecology. For years they have been doing crazy collaborative art performance–weddings with the elements claiming that Earth is our lover. By coincidence, Ewelina Jarosz, with whom we established the Cyber Nymph duo, got a scholarship at Santa Cruz University in California where Beth Stephens is teaching. Ewelina had an idea to marry beautiful brine shrimp (Artemia Franciscana) from Great Salt Lake and suggested that we should collaborate and involve Annie and Beth as well.

We asked Annie and Beth if we could use the script of their weddings and if they want to take part in it. Even though they were super busy (at that time they were promoting their book and they were traveling around the United States) they were happy to join us at the Great Salt Lake. The Great Salt Lake is at its lowest level in known history which threatens brine shrimp lives, through the wedding we wanted to show the difficult situation they are in.

CO: Have you observed any long term impact of your projects? Are any of your projects still ongoing?

JG: Yes, we’re continuing this project with the Cyber Wedding to the Brine Shrimp, and now I’m 3D printing our babies, our hybrid baby shrimps. I am also working on an experimental documentary about the project. A shorter version of the documentary of our wedding was shown this year in the first edition of Post Pxrn Festival in Warsaw in an ecosexual projections theme. It was also nominated for the prestige program AFI (Artist’s Film International) run by Whitechapel Gallery in London.

CO: You’re talking about ecosexuality but I guess that goes hand in hand with the hydrofeminist theories of being in synergy with all bodies of water. Do you remember when you started working around hydrofeminism?

JG: It came naturally. I think I heard about the hydrofeminist movement only last year but I’ve started to work with water already some years ago. For example, through the ongoing project WetMeWild which is a performative incarnation of a Slavic nymph. I think this was the beginning when I felt the need to think about the water as a transcendental matter, the element that is giving life and creating life and everything is made of it. Water also appears in my projects digitally.

The last AR app I designed for one of my performances I called Nymph Tiers. Together with Zeynab Gueye we were performing as nymphs, covered by logos of popular bottled water brands, scanning our bodies with the app that was showing animated tiers coming from those logos. We also used the “water body” technique known from the butoh dance found in the 50s by Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno. This technique is based on the feeling of the water inside of you, allowing you to become a part of a universe of bodies through water flows.

CO: What is the inspiration behind your WetMeWild alter ego?

JG: My grandma… She grew up in the small village in Skawa (Poland) and I was always fascinated by how Catholic she is, while at the same time she is doing these small rituals that originate from the time before we were Christianised, like feeding ghosts. So, I was really challenging her, asking many questions about it. What is the meaning? Why are you doing it? She comes up with the story of my great grandfather who told her that he saw the water nymph once in our river in the forest. Then I’m visiting my grandma, and if you saw this river, you’d see that it’s very dirty with a lot of plastic pollution, pesticides and household sewage. I was thinking, okay, this magical creature used to live there, my great grandfather saw it. But, I’m wondering how she would survive now in this world?

Making socially engaged art, I think, does not threaten my creative personality. However, it takes away from me a certain consistency with the aesthetics realised in projects, which the art market now expects from contemporary artists.

CO: I think it’s interesting taking these folklores that have been around for so long. And then your Instagram WetMeWild is a nice contrast between the very old and very modern. Your Instagram displays your practice in a very engaging and interesting manner. Do you consider it to be an extension of your practice or is it just a tool to present?

JG: Oh, yeah, it’s my extension. When I started working on this incarnation, the first appearance was the Instagram profile. I started to build her identity online. So at first it was, I would say, even more virtual than real.

CO: Which direction will you take in the near future?

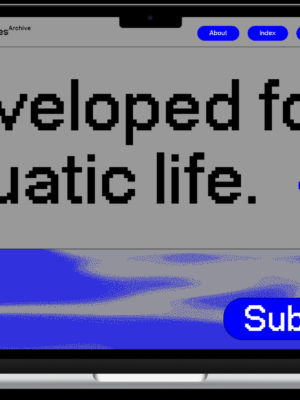

JG: I’m currently curating an interdisciplinary project with Ewlina Jarosz called The Blue Humanities Archive. We collect works that are at the intersection of digital art, environmental humanities, and emerging technologies. We want to support the protection of the depleting biodiversity of salt and freshwater in the form of a web archive. At the end, we are hoping to store this archive in one drop of the water using DNA digital data technology that is able to encode binary 0 1 code into nucleotides A C T G. In this way, considering ecological costs of storing digital data.

CO: Your work is very highly conceptual and does a lot to raise awareness of environmental issues and issues affecting society. And I wonder, is there a challenge in creating art that’s accessible to a wider audience without compromising your own artistic vision and integrity?

JG: Making socially engaged art, I think, does not threaten my creative personality. However, it takes away from me a certain consistency with the aesthetics realised in projects, which the art market now expects from contemporary artists. It wants us to be recognisable individuals who build its art brand. On the other hand, I love collective, interdisciplinary work where I often exchange competencies which sometimes requires me to change my previous artistic concept.

This interview is part of the Undisciplined. Crafting Conversations series, produced in relation to the pilot episode discussing Hydrofeminism hosted by Beatrice Alvestad Lopez and Bronwyn Bailey Charteris. For more information, follow Undisciplined. Crafting Conversations on Spotify and Instagram.