Beginning the journey from Munich, a drive towards goldsmith Rudolf Bott’s studio takes roughly an hour of travel through the bucolic Bavarian countryside. If you’re lucky enough to get a ride from Istvan, the good spirit of Galerie Zink Waldkirchen, you may discover that aside from his curatorial talents, gallery director Michael Zink courageously experiments with making schnapps out of beets, pears, and other nature given fruit at his home far out in the Bavarian countryside. Crossing a field, our car pulled up alongside what was once the school house of the local village. Today, it is the charismatic home and workshop of Rudolf Bott. Entering a hallway, I peeked into a neighboring room where a wide arrangement of hammers were neatly organized in wait for their friendly owner. If you’re someone seduced by the romantic possibility of unemployed anvils waiting for action, the anvils in his space could fill your dreams for weeks. ‘That’s Rudolf,’ Zink told me, as we headed upstairs together. ‘Each tool has its own very specific purpose.’ On the first floor, some of Bott’s past work was carefully arranged on a table for display. Amongst them, a silver candlestick and a rock crystal drinking glass emphasized how Bott holds a rigorous approach towards investigating material and form, and can do so in a variety of mediums.

Bott’s belief that aesthetic specificity exists within a given material is on display within the piece currently housed in the Artcurial showroom, entitled Tischobjekt (2020). A stunning table of poured aluminum, the work reflects Bott’s preference to not force materials against their natural properties. Elevated on a pedestal within the showroom, Bott’s table includes what appears to be craggy landscapes on its surface. Bott allowed liquid metal to melt out the wooden model in the casting mold, creating textured landscapes which document the pouring process as well as that moment of creation. At one point during our conversation in his home-cum-studio, throughout which Bott radiated enthusiasm for his craft, he brought up the example of a ruby. ‘The visual difference between a ruby and glass of a similar hue may be slight,’ he told me, ‘but there will always remain an inherent quality unique to the material itself.’

‘The visual difference between a ruby and glass of a similar hue may be slight,’ he told me, ‘but there will always remain an inherent quality unique to the material itself.’

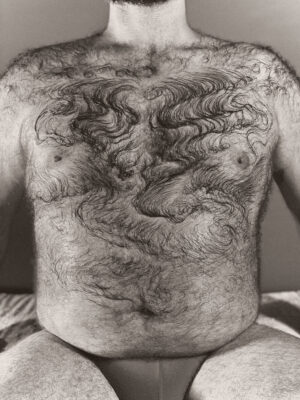

Continuing my tour in the Artcurial showroom, Paul Kooiker’s piece Untitled (2020) hangs harmoniously above Bott’s table. Reminiscent of a Japanese woodcut, the black and white photograph depicts curls of carefully arranged, decorative chest hair. Kooiker’s sepia-hued images, vaguely analogue and playful by design, pop forth dramatically against the green walls of the showroom. Despite the fact that these images have been taken with an iphone, their aesthetic reads as timeless. His approach, where digital images remind one of daguerrotypes, offers an ideological contrast with Rudolf’s work in its aims to highlight a given material’s specific strengths.

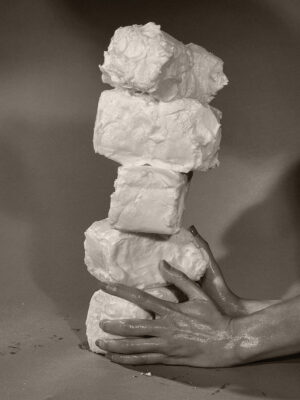

Standing by a neighboring table, Zink lifted a lid off of a trio of silver towers, allowing hanging metal spoons to jangle against one another pleasantly. The British silversmith David Clarke’s piece Stash (2020) is created from silver, pewter, and unclassified metals. His title comes from British slang, referencing the idea of a hiding place. ‘At a local market near where I live,’ Clarke told me over Zoom, ‘called Chapel Market, cleavage is sometimes used as a hiding place for money and drugs.’ The reference to breasts is evident in the rounded humps of the three lids, but as a collection of objects, I first thought of the anachronistic affect of traditional silver tableware. In this way, Clarke’s work deconstructs the idea of the ‘good silver’ but also (quite literally) reassembles it alongside other metals with a smirk. Created during the pandemic, Stash celebrates what Clarke was missing during that period: opulence, socializing, and community. He’s very happy to give silver a new role within his work, a role motivated by the traditions of silver but which also engages with the exclusive status silver can connote. On the wall behind Clarke’s stacked stand, a Kooiker photograph of a donkey (The Rumour, 2020) looks darkly towards the containers, unamused by the evocative centerpiece. Clarke enjoys the pairing between Stash and the hooved mammal, which for him, suggests a link between animal and human elements.

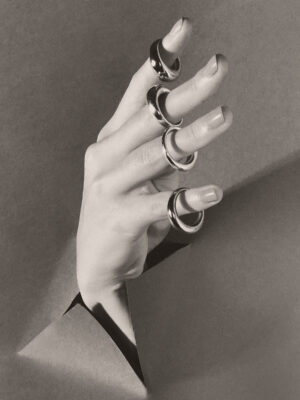

‘He treats these rings as sculpture,’ Zink told me. ‘And he doesn’t really care if someone wears the ring on their finger for half an hour in front of the TV, or if the ring is locked in a display case.’

Climbing Artcurial’s spiral staircase, a wide range of rings by Karl Fritsch are displayed upstairs on round, rotating pedestals. Zink encouraged me to try one on, and I gravitated towards an oversized, chunky piece so heavy that my wrist flopped over in mild protest. Fritsch’s work is unconcerned with producing something perfectly wearable, and his techniques often dispense with the conventions of his classical training. He has drilled through diamonds, opted out of polishing precious metals, and paired valuable material with inexpensive glass. According to Zink, there are artists who manage to bring about certain paradigm shifts within their field, and Fritsch has challenged jewellery as a medium. ‘He treats these rings as sculpture,’ Zink told me. ‘And he doesn’t really care if someone wears the ring on their finger for half an hour in front of the TV, or if the ring is locked in a display case.’ Zink energetically held up another Fritsch ring for shared inspection. A lovingly curated tower displayed a role of nails, sharp tips exposed, reminiscent of vertical knuckles. (Untitled, 2021.) The wide array of the rings, their variety of size and the technical treatment they’ve endured, whether hammered or squeezed into shape, suggest the dazzling range of Fritsch’s imagination.

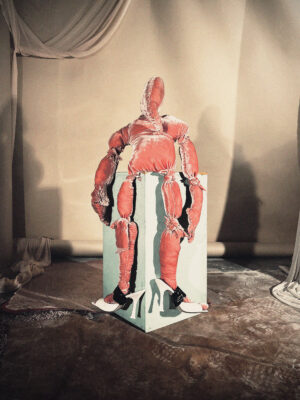

Back downstairs, an adjacent room presents visual symmetries between pieces in a satisfying curatorial wink. On the wall hangs a Kooiker photograph where a hulking bodybuilder with a rope tied around his leg is visible, with his face hidden from view. (Untitled (muscles), 2019.) The rope appears to be alive, the bodybuilder fighting like Laocoön with snakes. On the table below, a piece by the Swiss jeweller David Bielander rests: a snake has swallowed a rabbit, with its fur exposed through metallic scales. The embodiment of a fable, the 2023 work entitled Hase in Schlange (#00), brings to mind the snake in Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Le Petit Prince. Just like a real snake, Bielander’s piece is flexible and adjustable. It reminds me of a macabre feather boa. ‘Well,’ Bielander told me, adjusting his bright blue glasses. Apparently, a client does enjoy wearing his work around her neck while shopping for groceries. This image of a woman doing everyday shopping while exuberantly wearing a metal snake stuffed with a rabbit- made me smile. The story underscores Bielander’s belief that what we wear becomes easily associated with our personhood. In reference to his colleagues in the show, Bielander mentioned that ‘the questions may be the same, but the parameters are different.’ His own core interest in jewellery is uncovering what the field makes possible as a medium or genre, and what kind of stories he can tell within its embrace. ‘How do I get someone to wear a work with a new function and then go into a public space with it?’ he asked. I started brainstorming heady possibilities involving all kinds of high-stakes bribery, then realized his question was rhetorical. ‘It’s not that hard to make a two and a half meter long python as an object, he told me. ‘But,’ Bielander paused, ‘I don’t think it’s simple to make one that someone will wear within a daily situation.’ As I headed down the stairs from Bielander’s studio in Munich’s Westend, I imagined myself wearing a python during the comfortable ritual of brushing my teeth before bed, refusing to acknowledge that anything was out of the ordinary.

During my visit to Bielander’s studio, I reached out my hand and touched the snake, surprised to feel the jarring juxtaposition of metal against soft, quite delicate hair. Kooiker’s photograph of a man battling a rope highlights the tactile nature of the elements it contains: a contoured, reflective human back alongside the three dimensional, sculptural plasticity of rope. Zink’s pairing of these pieces work beyond visual correspondence. They are also attuned to the uncanniness of how a bodybuilder moves through the world and the dark, absurdist underbelly of Bielander’s piece. Were this snake to come to life in the midst of the gallery, struggling against the likely indigestion involved in swallowing a rabbit whole, it might twist around and lift its head towards Kooiker’s photograph. Before slithering out of the showroom with a hiss, the python might take a moment to revel in the varied concerns of these five, very different artists.

‘It’s not that hard to make a two and a half meter long python as an object, he told me. ‘But,’ Bielander paused, ‘I don’t think it’s simple to make one that someone will wear within a daily situation.’

Nonchalantly combining these four artists from the world of craft with the incredible work of the photograoher Paul Kooiker gives the exhibition a lightness and, as it were, an intensity that these artists might struggle to achieve on their own. Combining craft and fine art is an established part of Zink’s curatorial method. In the past, rings by Karl Fritsch have been juxtaposed with playful etchings by Jacques Callot from the 16th century, or ceramics by Johannes Nagel were combined with the alabaster-like paintings of Brazilian artist Rosilene Luduvico. Michael Zink dissolves boundaries and emphasizes how powerful and groundbreaking good works of art can be, whether by a goldsmith or silversmith, a ceramist, a painter, or an old master.

***Please note that conversations between artists, with the exception of David Clarke, were conducted in German and translated.

5 Gentlemen doing things. Galerie Zink in cooperation with Artcurial Germany. Galeriestraße 2b, Hofgartenarkaden, Munich.

Discover more about Galerie Zink Waldkirchen at www.zink-waldkirchen.de

To see more of Paul Kooiker’s work, his show ‘Smooth Cotton’ is at Galerie Zink Waldkirchen until May 7, 2023. This show is an extended continuation of his exhibition ‘Fashion’ at FOAM Fotomuseum Amsterdam.

This article is published in the printed edition of Munich Jewellery Paper, which is available for purchase through our web shop. Click on here to purchase the Paper.