Liesbet Bussche:

You were born in Budapest in 1982, the eldest of a family of four. Can you take me back to your childhood in Hungary?

Réka Fekete:

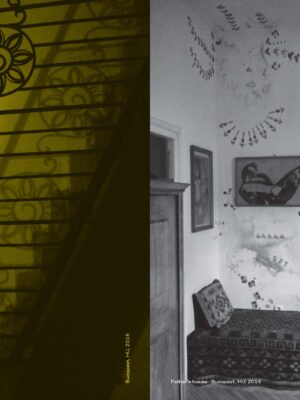

I grew up in my father’s childhood home, a Bauhaus house that my grandparents moved into during the Second World War after their own house had been bombed. My grandfather was an engineer and an artist, my grandmother a ceramicist and jewellery designer. My grandmother’s workbench and soldering equipment stood in the corner of her bedroom. This is where she designed mainly large jewellery pieces that were worn on the catwalk. When I stayed with her, she would let me bend a piece of wire and would then solder it for me.

LB: You told me that your grandparents surrounded themselves with artistic friends with whom they exchanged works of art. How did that particular environment influence you as a designer?

RF: There was art everywhere in the house, every object had a story. But it was not a museum, I could touch everything. I spent my teenage years mostly drawing and doing craft work at home. Only later, in Amsterdam, did I build up a large circle of friends. If my little brother or I had made something beautiful, it was hung up in the best place in the house. Every table was occupied, we all worked everywhere. I still recognize that in myself. When I’m working, I use every inch of space in the house.

I shared the spacious ground floor with my brother, which allowed me to withdraw into my own environment, but I had the world of my family around me. I liked that. That’s why I’ve always had a studio at home. The thought that you can carry out an idea at any time of the day is something I find both a necessity and a luxury. People ask me if I don’t feel pressured to work all the time as a result. But unfortunately, that’s not the case. (laughs)

LB: The constructions and mechanisms of an urban environment often serve as sources of inspiration in your work and make up both substantive and formal threads in your jewellery and objects. What traces has the city of Budapest left in your artistic practice?

RF: The architecture and the many Bauhaus houses in Budapest certainly inspired me, although I also understand why people sometimes find them boring or ugly, those square blocks with large windows. But with a trained eye, you can make out the details. We also visited many museums, dance halls and film evenings in the city. That was very influential in my life, even though I was brought up quite isolated and this is only one aspect of Budapest. The city consisted mostly of little islands that I went to, with roads in-between that felt strange. I remember sitting on the bus, looking around and thinking: I don’t belong here. In general, people didn’t radiate happiness, they weren’t really accessible.

LB: Is that why you came to the Netherlands as an exchange student when you were 17?

RF: Hungary’s hierarchical society and mentality didn’t suit me. The exchange organization thought that studying abroad would result in greater understanding for each other, for being different. A year earlier, we had been on holiday in the Netherlands and I liked the fact that it was very colourful: doors were painted blue or green, bicycle lanes were red, lampposts were striped black and white. That appealed to me at once and I could well imagine what it would be like to live here.

My stay in the Netherlands felt like a journey of discovery where I had to familiarize myself with a new world. And, it was easier to rebel here than in Budapest. I loved having a kind of freedom that was lacking at home.

LB: Four years later, in 2004, you moved permanently to the Netherlands. After moving around a bit, you settled in Amsterdam, a city you also describe as a self-selected home. By now you’ve been living in the Netherlands longer than in Hungary. What do the Netherlands and Amsterdam mean to you?

RF: I’m still a Hungarian, but I also feel like a Dutchwoman. Or rather, as someone from Budapest and from Amsterdam. Amsterdam suits my personality better, how I want to be. I like how people live together here, how they are involved in society.

I was 22 and it was the second time I left everything behind. In the Netherlands, I was simply a Hungarian student without people knowing what my background was. The family you are born into plays an important role in Hungary, although I wasn’t aware of it. In the Netherlands, it depended on the energy I put into a friendship, what kind of person I was, whether people were willing to help me or listen to me. I’m happy that the lifestyle and friendships I developed here are similar to those in Hungary.

LB: What began with a movie night and pizza has evolved more than ten years later into a cherished friendship. We met while studying in the Jewellery department of the Gerrit Rietveld Academie, a school that has a great impact on its students. Why did you choose this school?

RF: My parents really wanted me to go to art school, but I wanted to become a social worker. I had actually been accepted in a course in social work in Hungary. My father laughed at me, claiming I would bring everyone home. He said that wouldn’t work.

LB: I think he had a point there.

RF: Or else I had learned to care less about other people’s problems thanks to this course. (laughs) When Hungary joined the EU, I was finally allowed to study officially in the Netherlands. After four years as an au pair and doing all kinds of jobs, I wanted to go to art school. I don’t think you can become an artist if it doesn’t come from within yourself.

I was admitted to the first year in both Utrecht and Arnhem. At the Gerrit Rietveld Academie, I had to take a preparatory course, because the teachers thought my style was too distinct. As this was a part-time course, I could also work on the side. That’s one of the reasons why I chose this academy. Only later did I realize that the Rietveld is more conceptual than other Dutch academies.

LB: I see what you mean. You could describe the Gerrit Rietveld Academie as conceptual, but to me it’s also an academy where ‘making’ takes centre stage. In the first year especially you’re encouraged to do, to create. When I look at your process – an intuitive, material-oriented way of working in which designing, making and reflecting are tuned to one another – I can imagine that you were right at home there.

RF: I felt like a fish in the water. I found myself with like-minded peers from around the world who were all thinking the same thing as me: what are we going to make today and how are we going to do it? I found the idea important, but I wasn’t used to having to explain or defend my thoughts all the time. And I never intended to make political or socially relevant art. I let myself be led by my emotions.

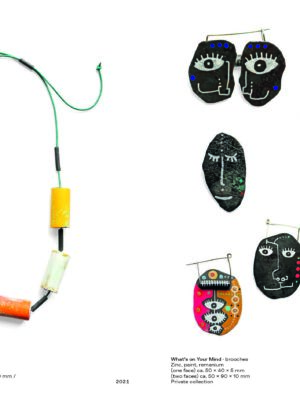

LB: Did you choose the Jewellery department because your grandmother made jewels?

RF: Not at all. I found Fine Arts, DesignLab and TxT (Textiles) interesting. But Fine Arts was too chaotic for me, DesignLab was too computer-oriented and TxT wasn’t what I had imagined. When I came to Jewellery, it felt like a warm bath: the programme was structured, students had their own table and you could work with any material imaginable. To me it was a bit like miniature sculpting, which I recognized from earlier, only now it had to become jewellery. It ultimately demanded a lot of effort. I was more concerned with the relationship to the body than with literally making it wearable. It’s only in the third year that I first made a brooch.

LB: Describing jewellery as small sculptures will rub many jewellery designers the wrong way. Do you still think this definition applies to your work?

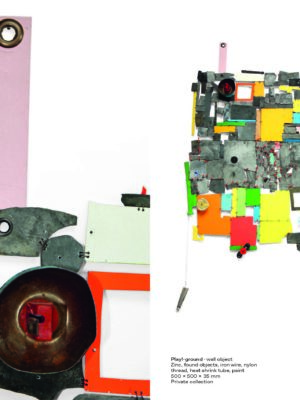

RF: I regard my jewellery as fully fledged objects that can function without a wearer. The wearer, or the maker, is not needed to let it be ‘something’ explicitly. In any case I give objects, animals and plants a personality, and therefore also my jewellery. During the creative process, they join in the discussion about the end result. They are creatures that function without me, companions you carry with you.

LB: Earlier, you already mentioned the importance of emotions during the making. How would you describe your work process and how do your emotions contribute to it?

RF: How I look, react and make decisions is my vocabulary. While designing, I follow a thread that helps me to make choices. I have a language in my head that everyone understands but which I cannot necessarily articulate. That’s not necessary either, you feel whether it’s right. It’s important that there is room for the interpretation of others besides my own meaning.

What happens in my life is not always visible in my work. I don’t focus on where I am, but on where I want to be. I’m currently making jewels that incorporate a lot of colour, as if they emanate a kind of joy of living.

There is a lot of darkness, but I consciously choose to show ‘light’ too.

LB: The darkness you mention refers to your illness. In 2016 you got breast cancer, which has now returned and metastasized. It’s very hard and I say it with tears in my eyes, but the prognosis is that you’re not going to recover. What impact has that had on your personal life and artistic practice?

RF: I live more consciously. When I was still studying, perfection and imperfection played an important role. I strived for perfection until I realized how unattractive and boring that was. I think it is precisely out of imperfection that a personality can emerge in which intimacy lurks. Imperfection makes you human. This issue also returns in my work, in which straight lines are not quite straight but give the impression they are. That makes my actions as a maker visible.

When I heard that I was sick again, I started wearing more jewellery, which I didn’t dare do before for fear of being noticed. I express myself with jewellery now, because my body does that less and less. Jewels are beautiful because they’re essential. They are a symbolic collection of all kinds of things in life that ends up in a small place as a kind of bundle that is wearable and goes out into the world.

LB: We share a certain ambivalence towards jewellery and we’ve had many conversations about jewellery and our field. What is your current position?

RF: I felt restricted by the idea that a piece of jewellery must last forever. We accept that everything we wear decays, except for jewellery. I find that unfair because I think it’s important that a jewel should live.

The restriction that you can only make jewellery makes no sense either. I find exhibitions involving different disciplines so much more exciting to see. I’m a maker. And yes, I even make my own bookcases. I don’t want to limit myself to one discipline. Works in different sizes and with different materials inspire each other. When I draw or build larger objects, that often returns in my jewellery.

I don’t know if it’s the same in other segments of the art world, but I find the jewellery world far too mannered, too polite. I’m not tidy, my work isn’t tidy, and yet it ends up in neat little places. Maybe I largely imposed this limitation on myself, but the jewellery world sometimes feels too oppressive.

LB: I could see that struggle, but I didn’t always understand it. To me you’re a jewellery designer through and through. It’s so natural in your creative process, in you.

RF: In my jewels I focused mainly on the object and less on how they communicated with the body. They gradually became more ‘jewel-like’ and I embraced their objectness as a quality. I came to appreciate the beauty of jewellery more and more. (hesitantly) It took me a long time to accept the idea that a jewel can be a jewel, that it can adorn, embellish. I was afraid that the substance would be lost and the aesthetics would gain the upper hand. Now I trust that this won’t happen. And if it does, so what. It is in fact very special to experience a childlike freedom, but now with more knowledge and experience. The funny thing is that in recent years I often thought that I would never design jewellery again. But now that I have all the freedom to make what I want, I think in jewellery. I didn’t see this coming. It’s kind of surprising.

LB: What does this mean to you?

RF: I realize that I have to spend the time I have left well. I want to continue making and telling stories as long as I can, but only from an inner need and without worrying about the positioning of my work in the field of jewellery. I was convinced that a powerful inner critic was holding me back from creating in recent years. I now know that not only myself but also the gallerist, the collector and the entire art world were lurking in my head as critical voices. I no longer have to answer to anyone. When you stand so firmly behind your own feelings and ideas, it no longer matters what people think. I like showing my work to the public because I want to show myself. But I no longer care whether someone wants it or not. I don’t even know if I want someone to buy it or not. I want it to be there.

This has probably always been the right way to create. Maybe there were too many things I didn’t dare tackle and in a sense I kept playing it safe. I also have a deadline now, though of a different kind. And the ending is different. It still feels strange that I’m still here. When I hear that this disease is affecting someone else, I’m really shocked. Imagining your own death is very different. I can’t really do that yet. But it’s not an obstacle. I only hope I have enough time. I don’t know how much, but every day counts.

Translation: Patrick Lennon

————————————-

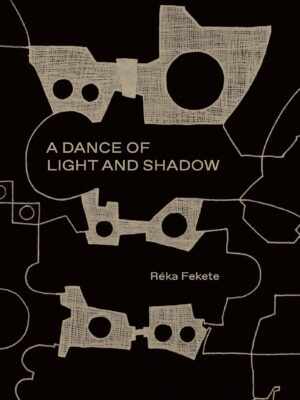

This interview has been published in:

A Dance of Light and Shadow, Réka Fekete

Editors: Réka Fekete, Liesbet Bussche, Beppe Kessler

Authors: Liesbet Bussche (interview), Ward Schrijver (essay)

Image editing & design: Haller Brun, Amsterdam

Translation: Mari Alföldy (Hungarian), Patrick Lennon (English), Roelien Plaatsman (English)

Paperback, cahier stitch | 208 pages | 24 x 16 cm (h x w) | Dutch, English, Hungarian

ISBN 978-90-803081-9-0 | 301 copies | € 39,00

BOOK SALE ‘A Dance of Light and Shadow’

Available from 25 October 2021 at:

* CODA Museum shop, Vosselmanstraat 299, Apeldoorn

Tuesday to Friday (10:00-17:30), Saturday (10:00-17:00), Sunday (11:00-17:00)

Or for more information, please contact us at bookreka@gmail.com