Helena Julian

How does Museum Arnhem usually work with its collection?

Anne-Karlijn van Kesteren

When I first started working here two and a half years ago, a specific position was created for a curator for the jewellery collection. Jewellery is not necessarily a part of the collection that comes to mind when you think about Museum Arnhem, but we have a rather large and important collection with an interesting history. We have more than 900 jewellery pieces, dating from approximately the 1960s to the present day. The main part of the collection is rather traditional, but starting in the 2000s you can clearly see that we began to look for a different interpretation of jewellery as a whole. Now, we see our jewellery pieces as examples of body-related design, which spans both jewellery and fashion. In our policy on collecting and presenting, we work from an interest in current events. We look at our collection with these in mind, and see how the collection can be opened up. Discussions about identity, gender and beauty come back regularly, but so do topics such as sustainability and circular design. For the jewellery collection we are searching for approaches that are more interdisciplinary, linking fashion, product design, ceramics and jewellery. Next to the jewellery collection, Museum Arnhem has an exquisite collection of modern and contemporary art pieces and a historical collection that is presented in the Erfgoedcentrum. When we think of our re-opening, we envision a significant dialogue between all the components of our collection.

What have you been working on recently?

Museum Arnhem tries to explicitly make exhibitions around urgent themes in society. The exhibition Body Control reflects on body politics, which fits with the museum’s larger intention to reflect on current issues. This is explicitly how Museum Arnhem tries to differentiate its jewellery collection from other collections throughout the Netherlands. In a national sphere of a limited size where many institutions are collecting jewellery, it is increasingly important to have your own identity. Body Control tries to make a step forward in showcasing how Museum Arnhem deals with its collections and how current jewellery design connects with fashion design.

How was Body Control developed?

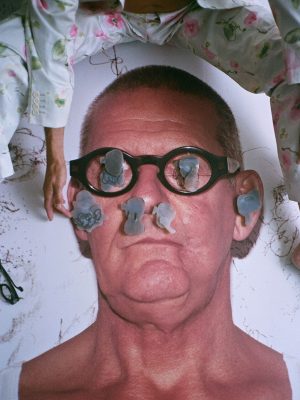

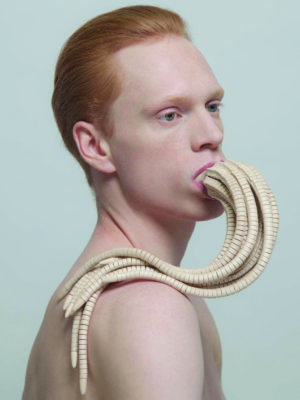

When I started working at the museum, one of the first purchases I made for the collection was work by Frank Verkade. He is trained as a product designer, although he continues to question if the object is still wearable or has become a visual art object. This is significant to us at the museum: trying to always start from the position of the body and the story behind the piece rather than from the position of traditional materials and techniques. I had interesting conversations with Frank about what students are busy with at the academies, and about the increase in interdisciplinarity. In recent years we have also seen more exhibitions about jewellery and fashion relating to the body and beauty in general. I then started to search for more topical issues within society to relate to the work that is currently being made. Each piece presented in the exhibition is a reflection on our human condition and the borders we try to search for in the human experience. Some of the pieces have very personal stories, but many reflect on larger themes such as plastic surgery or the influence of social media on self-awareness. Jewellery and fashion may be seen as beautiful ways to reflect on the human condition, because they’re carried so close to the human body. Just like the recent pieces in the collection, the exhibition starts from the body. The many voices we have selected are often very critical about the issues they address, but we don’t pretend to hold all the answers. We prefer to bring together all the narratives produced by these artists who work through jewellery and fashion. An artist often has larger intentions for a piece than simply having it exhibited; many of the works envision having an influence on the real world. All of these narratives are reflections, visions of the world that we live in; they give us insights into how jewellery can reflect on societal issues.

How does the exhibition open up the body-related pieces from the museum collection and display the newly presented pieces?

All the work exhibited in Body Control was made after 2000, and you can clearly see a shift in how jewellery and fashion is considered in the new millennium. For the selection I did a lot of research, of course, and there was an international open call to academies around the world, calling for work from students and graduates. The distinction was that all the work needed to have a concrete conceptual link to the body. Most of the exhibited work comes from Europe, but there’s also work from Israel, Australia, Russia and America. The exhibition is designed by Maison the Faux, an Arnhem-based fashion duo who have worked a lot with fabric design. We have worked with a grid that carries fabrics and also forms platforms for the pieces. It will be an extravagant presentation with mostly larger objects; the smallest object will be a ring.

How do the broad thematics of body politics become present in the exhibition?

I chose to work thematically, with a diagram of subjects that I saw present in contemporary discussions. The exhibition is split into three spheres: Human, Outer Human, Superhuman. An important part is, for example, dealing with how the digital sphere has influenced our human condition, from social media to face recognition software. Another part is about (im)perfection, where we look at design that reflects on how the outside world impacts our self-image. For example, the possibilities of plastic surgery and how it deals with bodily imperfections – what is considered more or less beautiful. Then we have a part that deals with sexual freedom, about the control that you have over your own body and your sexuality. Another part, called ‘man/woman?’, deals with identity, and focuses on designers working with gender. The exhibition doesn’t take a point of view but tries to show the wealth of viewpoints among the designers and their research questions. Many of these works deal with what it means to be male or female, and how this is made visible to the outside world through bodily appearances such as hips and breasts or the Adam’s apple. One work in the exhibition, for example, provides an opportunity to wear an Adam’s apple. The last part of the exhibition concerns our own mortality and ageing, and what we do to counteract these processes. It questions the desire to become a cyborg, and traces this back to historical examples showing that we have long supported our bodies with the aid of different accessories.

Are there any other initiatives the museum is setting up while it is closed?

We will continue to make exhibitions in De Kerk until the end of 2020. You can also find the museum at several festivals and initiatives throughout the city. Next to that, specifically geared towards the jewellery collection, we are working towards making Sieradenmuze – an online platform inspired by the fashion platform Modemuze, which was launched in 2014. It was initiated by seven museums that have garment collections with the goal of increasing the visibility of these collections, as it remains difficult to exhibit textiles. Modemuze has grown into a large platform, and through it these collections have become more visible. Together with Modemuze we developed Sieradenmuze, as some museums with jewellery collections also have the desire to become more visible. Sieradenmuze will go live in about a month and we are working with several partner institutions throughout the Netherlands, such as CODA, Design Museum Den Bosch, TextielMuseum, Centraal Museum and the Rijksmuseum. It will become an interactive platform, where you can create an account and comment and like on the shown pieces, but also participate by writing blogs. We hope to create an active community. More to follow soon!

This article is published

in the OBSESSED! Jewellery Festival Paper.

OBSESSED! is a biennial jewellery festival taking place in various cities across the Netherlands. OBSESSED! unites the best jewellery-related events – museum and gallery exhibitions, talks, fairs, book presentations and artist open studios – into one intriguing programme put together by Current Obsession.

Body Control

Date 02–11–2019 until 26–01–2020

Location Museum Arnhem

De Kerk Sint Walburgisplein 1

6811 BZ, Arnhem

Website www.museumarnhem.nl

Monday Closed

Tuesday Closed

Wednesday 12:00–18:00

Thursday 12:00–18:00

Friday 12:00–18:00

Saturday 12:00–18:00

Sunday 12:00–18:00