According to Steve Jobs, Picasso once said, ‘Good artists copy. Great artists steal.’ That statement has been attributed to other creative spirits, varying from poets to composers. If you pay attention, you also find an improbable plethora of ‘copying’ in three-dimensional design. Joseph Hoffman’s famous square silver fruit bowl from 1910, the standard-bearer of an historically innovative movement in style, is said to have been based on an earlier work by his somewhat less well-known contemporary, Kolomon Moser. Nerrari Hardoy’s Butterfly Chair from 1938, often referred to as one of the most copied icons of modern design, turns out to be a variation on a forgotten predecessor, a folding stool designed in 1877 by Joseph Beverly Fenby. Jasper Morrison intentionally used an existing chair as his starting point for a new design, and anyone who does not look closely enough can barely see any difference between the example and its successor (the Sim Chair from 1999 versus the 40/4 Chair by David Rowland, made in 1964). These are somewhat shocking discoveries. Or is there something missing in our expectations about the innovative and original character of design?

Ceci n’est pas une copie exhibition brings copying in design into perspective, without all too many preconceptions. The exhibition presents a wide selection of strong designs that illustrate diverse visions of ‘copying’, while taking account of cultural differences between East and West and changing opinions and perspectives throughout history. Ceci n’est pas une copie also looks at the influence of new reproduction technologies, such as 3D printing, all in search of potential motivations, backgrounds and criteria in order to better differentiate between acceptable and unacceptable copying strategies. Ceci n’est pas une copie seeks out the nuances that can help advance the debate about copying.

If copying is in fact so ubiquitous, so inextricably interwoven with every form of human productivity and creativity, then it seems worthwhile to investigate the conditions that allow us to see it as a positive creative strategy. In addition to copying done sloppily, out of laziness or greed, there are also decidedly accepted strategies of reuse, including homage and reinterpretation. The living antipode to copying done in simple ignorance is intentional citation with acknowledged sources. Imitation of and eventual improvement on the work of the master, imitatio et aemulatio, was an important concept in the classical artistic learning process. Copying has long been a means of studying, optimizing, critiquing, experimenting or challenging. The distinction between imitation and innovation is not always easily defined, and the two extremes do not necessarily cancel one another out. A great deal of copying takes place in a confusing gray zone – somewhere in between.

Upgrading everyday objects

Copy as anti-cliché

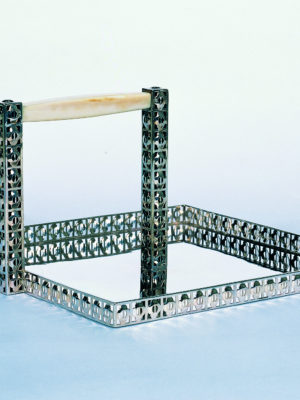

Hide De Decker (b.1965, BE) studied interior and jewellery design. Her work can be seen as in between jewellery design and autonomous fine art. She investigates how ornamental objects acquire their special significance. Foe her, wearability, technical execution and aesthetics are subservient to the (symbolic) meaning. Form. material and technique are important only insofar as they affect the meaning of the message.

Since the 1990s, many of the themes of De Decker’s work have a direct, almost autobiographical connection to everyday life: the feminine, the domestic, the mundane and the transitory. By ‘copying’ banal domestic objects in silver or gold, shifting them into the context of precious jewellery, she strips them of their everyday character. Not only do they acquire a higher material value, they also convey inconsistent messages and have a disorienting effect. Jewellery expresses values that transcend the material or aesthetic, such as status, or emotional and symbolic value. Consider family heirlooms, or jewellery commemorating spacial moments in our lives.

Which category might apply to Hilde de Decker’s objects from her 1996 Homecraft project is uncertain. She sought objects that had been part of her childhood, present in and around the house where she grew up. By ‘copying’ them in silver, one might think that she wanted to express the objects’ high personal and emotional value, but there is more to it. She did not select the obvious, endearing objects reminiscent of a happy childhood, but ordinary utilitarian objects. It is not Proust’s Madeleine that she highlights, but madeleine cookie holds, suddenly inlaid with silver: a shift from the bourgeois salon gathering and its afternoon tea to the downstairs kitchens where all the work took place. She had applied her silver techniques to scouring pads, oven cloths, and tin openers. These silver versions of everyday objects from the 1960s and 1970s were originally presented in display cases, in an analogy to archeological finds in a museum of antiquities. The statement made by a scouring pad in a delicate knit of silver thread. or her later flycatcher in 24k gold. work at a personal. emotional level, but its precious medium automatically evokes commentary about the conventions and traditions of the art of jewellery making, which is strongly bound to idealised symbols and archetypes. De Decker sets that medium to her hand and uses it to express less gaudy, more naked version of realty.

In our digital age, it seems that discomfort about this lack of clarity is on the increase. The democratizing of 3D scanning and printing technology opens doors to even more, and more acrid, reproduction and copying. Traditional copyright and intellectual copyright law does not always offer the desired handhold, and standpoints are growing sharper. Proponents of stricter copyright regulations are opposed by Internet activists and utopians who see copyright law as a threat to creative freedom.

In preparing for Ceci n’est pas une copie, to help give a realistic picture of what is happening today amongst designers and design specialists, a questionnaire was distributed with questions about copying. Dozens of design professionals responded with written, personal statements on the subject, which will be incorporated into the exhibition. They include Jasper Morrison (UK), Volker Albus (D), Robert Stadler (FR), Piet Stockmans (BE), Sylvain Willenz (BE), Lachaert & d’Hanis (BE), Dirk Wynants (BE), Lowie Vermeersch (BE) and Matthew Strong (US). At the same time, the questions also painfully revealed how sensitive the subject is, and the invitation to share insights on this subject with the (museum) public caused not a few alarm bells to go off amongst those whom we approached. Many did not want to reply.

Nonetheless, there was certainly no lack of enthusiastic input. At some point in their careers, many designers have had to engage with this intriguing phenomenon and consequently referred to projects of their own, which fit perfectly into the theme of researching or experimenting with copying.

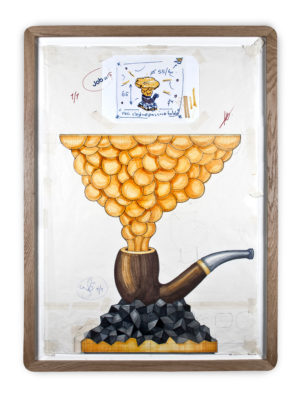

Statement by Sofie Lachaert and Luc d’Hanis: ‘For the work we do copying is perhaps not the right word. Our theme is more reworking. We use images, for example symbols and references from visual art in a different way and in a different medium. We rearrange, shift, turn functions around. We like the rather outdated term applied art, rooted in a craftsmanship of the highest order. The virtuosity of making something and executing it perfectly is something you can call old-fashioned craftsmanship, but inspiration is autonomous and unique unto itself. Just as it was for guild members six hundred years ago, blending techniques is essential. They mixed golsmithing, sculpture and painting. We mix up styles and materials until it is something unique, something new.’

Deconstruction and reconstruction techniques are regularly applied by designers who are much more inspired by the history of making objects, the process of making something, materials and techniques than in conspicuous individual expression or exceptional originality. Questions about authorship and originality play a major role, for example, in the work of the German designer Hanna Krüger (b. 1979). She too is fascinated by anticipated upcoming evolutions, now that more and more design objects in (museum) collections and archives are becoming accessible online and can be printed in 3D.

In Ceci n’est pas une copie, the investigative work of a number of intentionally ‘copying designers’ is included in the ‘Copy to Learn’ section (copying in order to learn, study or correct). Other categories are ‘Copy to Pay Tribute’ (honouring someone or something), ‘Copy to Continue’ (make something topical or bring it up to date), ‘Copy: Not by Design’ (unavoidable or unintentional copying), and finally, a group of designs inspired by the discussion about Chinese copycats, in ‘East Copies West Copies East Copies…’, in which the cross-fertilization between East and West is seen with the help of new interpretations of Delft Blue inspired by Chinese porcelain, for example, playful Western variations of traditional Eastern carpets, modern and contemporary approaches to Ming vases, chairs and paper light sculptures, and so on. In these five overlapping categories, the emphasis is on the creative character of copying. Entirely separate from all of these, there will also be a few examples of commercial plagiarism or piracy.

The Italian furniture designer Martino Gamper has lived and worked in London for 18 years, and is known for his live performances, in which he deconstructs existing furniture pieces and materials and rearranges them into something new. ‘If all we are doing is accelerating our endeavour for authenticity, and everyone thinks they have to be even more authentic and original, we miss the interesting parts, the bridges between different epochs, styles and movements.’ He considers innovation important, but he also believes in exchange and dialogue with history. ‘Just because someone invented a technique to bend wood doesn’t mean that no-one else is allowed to bend wood. These processes, these forms, these authors who shaped our history should be there as inspiration for us to be equally brave, pushing the boundaries, trying to reinvent things.’

The Dutch designer Richard Hutten has also thoroughly researched copying. In consultation with his clients, he seeks efficient methods to discourage copycats. His work also reflects great historical awareness. He has produced many designs inspired by existing designs, including his Berlage Chair for the Gemeentemuseum in the Hague. For his project for Droog Design’s ‘The New Original’, he and other designers traveled to the core of the Chinese copycat culture. ‘It was very interesting as a kind of counter-reaction: let us also go copy them for once, because they are constantly copying us, and legally, there is very little we can do about it.’ This experiment did not lead to literal one-to-one copies, but to improved, contemporary variations. ‘What you also see in copying is that an original can be improved. This is also what they are doing in Asia.’

The Dutch-Belgian design team of Unfold, with Claire Warnier and Dries Verbruggen, are a must for this exhibition. With Kiosk, a delivery bicycle carrying a mobile 3D scanner and printer, they intentionally copy existing objects. For Ceci n’est pas une copie, they have selected an exceptional exhibition object that they will copy for the exhibition. They want to stimulate discussion about what we can expect if everybody is able to print in 3D. Dries Verbruggen: ‘The Internet has meant that people think it is completely normal for them to copy something, adapt it, set it to their own hand, remix it. The vivacious remix culture is one of the most important cultural achievements that the Internet has brought. Of course, there have to be limits to what can and cannot be done. (…) It is a classic dilemma: as the owner of a design, do you take your fans to court?’

Marnix Smessaert, founder and business manager of the Dark design lighting studio, is rather more adamant in how he feels about those enthusiastic ‘fans’. He is more concerned about the enormous economic consequences. In his videoed interview, he shares his experiences of running a company and its battle against the copycats. Finally, Alexis Ewbank, a Brussels-based lawyer specialized in authorship and reproduction law, delves more deeply into a number of basic rights and obligations on the parts of designers and consumers, as well as the purchase of illegal copies.

In designing the setting, or scenography of the exhibition, the Ghent-based architecture studio of GAFPA found inspiration in the massive brickwork barrel vaulting that characterizes the former stable buildings at Grand Hornu, and more specifically by the temporary wooden moulds originally used to build the individual arches. Several of these semicircular wooden constructions are arranged throughout the space, introducing a new viewing trajectory. The moulds once again become temporary structures now serving to shape the exhibition.

Ceci n’est pas une copie is open at the Centre of Innovation and Design at Grand-Hornu until 26 February 2017.