Kellie Riggs:

Can you discuss your philosophy around the idea of space – or the differences between space in its physical and metaphysical sense? Is there a distinction?

Warwick Freeman:

Like everyone else, I use it to describe both my environment and my mental state – the visible and the invisible. But here in Aotearoa/New Zealand it also has some resonance when it can be used to refer to cultural space, and particularly in the arts where ideas are often appropriated from other’s ‘space’ – ‘the space between’ is used to suggest a space that exists between cultures – one that both parties occupy as a way of coming to terms with each other. Sometimes referred to as ‘negotiated space’ – the implication being it’s a credible space where the differing cultural viewpoints meet and negotiate how to get along. I’m actually not that convinced by the idea of a ‘space between’. I think we overlap, and those differences are either rubbed smooth or raw in that overlap.

Another big territory in the life of an artist that has a studio-based practice like myself is, of course, the workspace and how that is such a strong influence on what gets made. When the mind is engaged in making, it can let thoughts through – making is a thinking space.

Once again, I don’t think I see these ‘spaces’ as having separate identities – the physical and metaphysical spaces overlap and, just like in the cultural example above, reconciling them isn’t straightforward, but then the irritation is often a more conducive condition for art making.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

KR:

In your Two Headed Dog lecture, given at the Reconsidering Identity Seminar in Gothenburg, Sweden, you said, “…as a maker you have to create your own narrative associated with the role of the artist you choose for yourself and that’s where theory holds or folds – in the quality of your own narrative… you need to create a robust conceptual space around your practice or it will just knock you around.” What is this for you? You’ve said that it builds a narrative around your own concept of usefulness. Is that what you mean?

WF:

I need to have that ‘robust conceptual space’ to be convinced to make jewellery. I get that robust sense from jewellery’s history, which includes the more recent contemporary history, but more generally the long history of great work. If that ever ceases to be convincing, or if I’m not sure jewellery is worth it, then I’m ready to move on.

My own ‘concept of usefulness’? Usefulness is the most meaningful reason for making I can put into that space. You should always ask yourself the question – why make this? There are a lot of ways to answer that question. I tend to start with the premise the world doesn’t really need another piece of my jewellery so I have to create some sort of convincing narrative around why I make the things that I do. That narrative can be a simple or complex justification but we do it around food, clothing, architecture etc. to find meaning in the way we live. Jewellery is just another conversation that takes place within the bigger narrative of being an artist, a citizen etc.

In the 70s hippy era I used to like the expression a ‘craftsman of necessity’. It was the idea that you made something because it was necessary for your existence. Necessity is easier to work with – it suggests you can’t survive without it, and one can always survive without jewellery.

So ‘usefulness’, what does that mean? I quite like invoking the idea of usefulness because it begs the question from the artist: who will get some benefit – usefulness -from this thing I’m making? I need to build a relationship in my mind about how what I make gets to engage with my own culture – I would like it to have some integrity as an object in the cultural conversation. Most of the time we are busy defining the nature of jewellery (not a small task done properly) but just occasionally, when our work enters that larger domain, we get to define bigger conversations about ourselves.

KR:

Somehow I’d like to talk about identity, your connection to your own identity in New Zealand, and the myth of the place of landscape in New Zealand culture. Is your work a means for you to grapple with your place, the land on which you live and work, and what may or may not belong to you? And what about the importance of myth in your work and how that functions in the larger scheme of New Zealand’s own history?

WF:

When European settlers arrived in New Zealand the landscape was already named and its creation had been expressed though various myths about gods and demi-gods fighting amongst themselves – making mountains and carving out valleys. These stories are about the place I live in and they communicate a way of looking at it that, to find an equivalent in Western history, you probably have to go back to something like Greek and Norse mythology. The interesting difference is that the world was experienced in those mythological terms very recently here in Aotearoa. Those myths were a satisfactory description of this world until European settlement 200 years ago, when the alternative versions provided by Christianity and scientific discovery were imported. Their recent efficacy means these stories are included in the cultural space I talked about above, along with those European myths; they are part of our cultural capital. And the struggles of the demi-god Maui feel closer to my home than those of Odysseus.

KR:

An example of the above might be the Maori legend of Kupowai, the two-headed dog in which you’ve previously referenced, and how it enabled the Maori to name the world into existence. What is the importance of this legend? And the very idea of naming something into existence, why do you speak of this?

WF:

Legends are how we used to explain the world. Naming was a way of taking control of the landscape. We would never construct a myth like that out of the landscape now – but we still name it – we just use scientific language and describe it in terms of tectonic plate movements and other geological explanations for rocks, hills and mountains (in a volatile landscape like we have in New Zealand that story is being rewritten all the time). Needless to say we are still active mythmakers – just not in that old way anymore. But we still name our world into existence and I like how words are used to give shape to our existence – the way they can be used, like any material to make something. Naming is just a very rudimentary beginning stage of that making process – an important first step. I also like the next step – when naming becomes simple poetry. I make lists. I like signs. A lot of my work is sign-like. I start to lose interest when it becomes too visually sophisticated – I have a very reductive approach to making, generally subscribing to Modernist tenants – the ones that prefer lessness. I sometimes think this is a problem of skill – sometimes I don’t have the skills to complicate it further – for both the language and the jewellery. But if I do complicate it I invariably regret it and look for a way to draw the idea back to a more simple moment.

KR:

The fishhook is another example of creation myth or naming story, the Te Ika a Maui, or the demigod called Maui, who used a hook made from his grandmother’s jawbone and baited it with blood from his own nose. When did you realize you needed to make fish hooks, was it inevitable?

WF:

Ha ha – inevitable – I wouldn’t go that far. The fishhook is another archetype – I like the way it exists in all cultural spaces with such remarkable consistency. The fact that it inhabits this one in Aotearoa with potency is a good reason to engage with it.

KR:

You’ve described your hooks as the symbolic being made functional, where as in Maori culture they’ve done the opposite. Also, I’m obsessed with this story about the 1995 ruling by the New Zealand human rights commission; the fish hook was interpreted as a piece of jewellery, a pendant – a hei matau – worn today by Maori and non Maori; and this ruling determined it should be classified instead as a cultural treasure – a taonga. The outcome was that in certain places where jewellery was not allowed to be worn, this could be worn anyway.

WF:

I guess if we want to talk about ‘usefulness’ then this is an interesting way in which we can apply it to jewellery. Because of its association with myth and indeed survival, the hei matau is jewellery with a cultural usefulness and a strong symbolic meaning.

KR:

I guess if we want to talk about ‘usefulness’ then this is an interesting way in which we can apply it to jewellery. Because of its association with myth and indeed survival, the hei matau is jewellery with a cultural usefulness and a strong symbolic meaning.

WF:

It was a brief flowering amongst a group of New Zealand contemporary jewellers around the use of a particular group of natural materials native to New Zealand and the South Pacific. Some of us took our clues for the use of these materials from earlier pre-European examples of adornment – work of Maori and other Pacific Island production that’s housed in the museum collections in Aotearoa.

It had its main period of activity in the early to late 1980s. Paua shell (a New Zealand variety of abalone), pounamu (a New Zealand variety of nephrite), pearl shell, bone (both mammal and bovine), and various types of fibre and wood.

KR:

How do you see your place in this? Your piece Insignia (1997) comes to my mind, as a more contemporary and far more complex example of your relationship to this perhaps. It’s made up of six pieces: Shield, sandstone and quartz; Spot, jasper; Karaka leaf, nephrite; Eye, pearl shell; Bird, turtle shell; and Skull, cow bone.

WF:

That work uses the lessons I learnt about materials from the Bone Stone Shell era but now it is looking away from the museum collections of Pacific and Maori material and is looking at the jewellery history of emblem making. The emblematic sensibility was also very strong in the BSS work but I was using metal again and jewellery devices, like claws, from the European jewellery tradition.

KR:

In your 2013 lecture at the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich, you described yourself as a Weka, a type of bird that collects shiny objects with naturally no hierarchy to the object’s inherit value. You’ve also said at one point you still thought Contemporary Jewellery could just be a string of beads. Is that still true?

WF:

Yes. Strings of beads have a large presence in the history of jewellery and some of the contemporary interpretations of the form are still doing the job. I don’t think doing that job has much to do with varying the form but a string of beads should have some claim to being a string of beads from your own time.

KR:

I think your Lei pieces (Large Star Lei, Lava Lei) may describe this line of inquiry. Can you talk about them and why you wanted to create these welcoming necklaces?

WF:

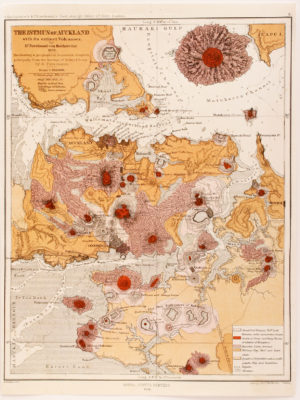

Mainly it’s a reference to the form. The lei is a necklace that is long enough not to need a catch so it can be slipped over the head of a visitor as a welcoming gesture. They are traditionally made from readily available materials – flowers, shell etc. I just extended that idea of available materials. Works like Heart Lei or Scoria Lei are made from a stone that is associated with the volcanic history of the region where I live – Auckland. So with the lei reading they become a welcome to Auckland necklace.

KR:

For you, what is the connection between material and place?

WF:

Much like I describe with the Lei necklaces – it is very immediate – as basic as where I’m standing. There’s a quotation by a highly regarded New Zealand Modernist painter, Colin McCahon, about his own work:

‘My painting is entirely autobiographical – it tells you where I am at any given point, where I’m living and the direction I am pointing’.

Colin McCahon, 1972

The lei necklaces from the late 1980s were made when I was very aware of the geological nature of where I lived and the political emergence of Auckland as the biggest Polynesian capital of the world. The ‘where I’m living and the direction I’m pointing’ connects the materials and the place.

KR:

It seems personal and delicate. For example, much of your work really relies on what the material of it is, that’s where the content lies, which again makes me wonder if you’re doing this as a pursuit to really allow yourself to belong to Aotearoa; is it that you’re not at ease with your own cultural identity (European roots vs Maori culture, you as Pakeha), or am I reaching here?

WF:

I don’t have any internal struggle with concepts like ‘belonging’ – I know some people take a lot of their identity from it and I don’t operate an ancestral system that has that relationship inbuilt. My ancestors have been in New Zealand for several generations and most of them were from Europe: English, German and Scottish as far as I know but the cultural identity I have assumed is Pakeha which makes me a person of European descent native to Aotearoa/New Zealand. That is more than enough identity for me to live and work with. I think the identity we are not at ease with is as a species on the entire planet. To quote a 20th century New Zealand poet:

‘All earth one Island, and all our travel circumnavigation’

Allen Curnow, 1943

I just live on a relatively unpopulated part of the earth but we know this much about our future – we are all implicated in the state of our ‘one island’. That notion aside I’m acutely aware of where I live and the distance involved in circumnavigation, and like McCahon, I’ve made my home in the local and at the same time have been in conversation with a Western art movement like Modernism. Sometimes the local is about cultural identity and cultural identity in Aotearoa/New Zealand can be about the complexity of living in a postcolonial culture, but for me it is not a struggle about belonging. Post colonialism is the given condition and I exist in that condition with my identity very intact.

KR:

As well as using found materials from the land, you’ve been known to remake found objects of various material and type. You’ve said there’s plenty of accident, but the process does have rules. Again from your Munich lecture: “Essentially the found object I am looking for produces a recognition that I can only describe as possessing something that relates to our deep memory – various shapes that have an identity – a character that we might refer to as archetypal.” To me this also relates to your connection to myth: memory is often a constructed one in the best of ways especially when exploring one’s roots. Would you like to talk about your relationship to memory?

WF:

I’m suggesting there is some sort of communal memory for shape – our common ability to identify shapes. That’s not hard to see with something like the circle – the pupil of a person’s eye, the shape of the full moon in the sky – they are both consistent over the entire planet. Other shapes aren’t so obvious but they often recur with a similar consistency (like the fishhook) and when I get that sense of recognition I’m not too bothered if I find that on the footpath.

KR:

I’ve also read you mentioning some kind of nostalgia for primitivism. What does that mean? Is it your nostalgia or New Zealand’s? Is perhaps your piece, Cutter (2010), an example, and how it compares to the 19th Century Fijian breastplate you found in a local museum?

WF:

One of my favourite works from the Auckland museum that influenced me a lot in the Bone Stone Shell period is that particular small breastplate work from the Fijian Islands. It’s a small gold-lipped oyster shell that has had 2 interventions that make it into a piece of jewellery: the holes for the string and the saw tooth cuts in the outer edge. Both technologically easy to achieve and of course the maker could have intervened more, but to me there is the sense that unnecessary decisions have been kept at bay by the limited technology. That’s where the danger of nostalgia can come into play – I have enough tech to make it better and so the decision not to – to make it look ‘primitive’ is definitely where nostalgia is a risk. There’s a definite line between the aesthetic of low tech and faking it.

A work like Cutter would be mannerist if it only took its meaning from the breastplate and didn’t have its origins in the found template provided by the tissue box cutter. I think that piece is an example of where the line is tested. I think the Bone Stone Shell movement started to unravel when lots of makers got involved who didn’t think about that line – their reason to make the work was only attached to the early adornment history by sentiment.

I don’t know if we have a particularly nostalgic attachment to the past in New Zealand – we have so little past to get attached to – the past is not that long ago in New Zealand. The land is old but not the people on it.

KR:

What about the future then? In Two Headed Dog you said, “It’s thinking that opens up ‘making’ to mean different and new things – so that it might have a future and not be reliant on tired old virtues such as ‘the one-off’ or ‘the handmade’. What do you mean by future?

WF:

Oh any future. I’ve heard the death knell for studio-based production sound several times over my 40 years of practice. As a way of making, studio-based production still persists, but there is no guarantee it will – certainly not in the form I practice it. It’s about never taking it for granted – you should think about that when you make.

KR:

Let’s talk about the stars. You’ve been collecting stars since around 1990, mostly through photographs, correct? Share of Sky (1990) was the first; when I saw this in Munich, my heart smiled.

WF:

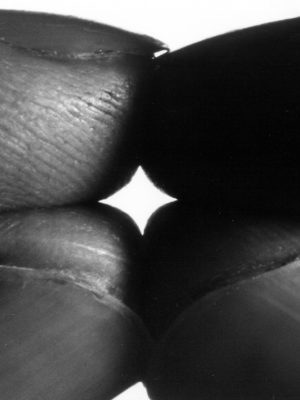

I started collecting images of four-pointed stars in the early 1990’s. The fingertip star image was the first one I made and that became the Ngataringa Star – 1990

The Share of Sky title comes from a novel by a New Zealand writer, Janet Frame. In it, a character is lamenting the isolation of her life in New Zealand to a visitor from New York. Drawing the New York visitor outside to look at the night sky, looking up she says by way of compensation:

‘but so far we all have our fair share of sky’.

The Carpathians, Janet Frame

Soon after I made the Share of Sky image I photographed two more found stars in New York (I just realised now that’s where Frame’s visitor character came from) and those images were the starting point for two brooches: Soft Star 1991 and Hard Star 1992. Since then, I have collected hundreds more. A few have produced pieces like those did but the collection of images – ‘I Collect Stars’ – is a work in its own right now.

KR:

I’d like to talk about Seven Sisters (2013) your ode to the Pleiades constellation, “witnessed by its different naming in may cultures… as a feminine attribution – seven sisters being one…” the pieces are made of stone, where as other stars of yours had been made by mother of pearl, which you’ve described as the “most feminine of materials.” Why stone?

WF:

The Seven Sisters work was probably the first four-pointed star I had made for some time and although pearl shell was a material I used a lot in the 1980s and 90s. It is a very beautiful, very seductive material, but maybe beauty and seduction aren’t what I’m pursuing with the work anymore. I made lots of pearl shell stars. Nowadays – less twinkle, more dark matter. Actually beauty interests me a lot. Trying to figure out how it works. I believe it does it by some sort of consensus – if enough people agree something is beautiful then it is – but I don’t have to agree with the popular vote.

KR:

You actually already explained this piece very well in your Munich talk, but I am really fascinated by it, this idea that this constellation, as with many, is visible from many places in the world, and that’s also how you see your work: “its distance from here is the same as its distance from everywhere.” It’s a kind of metaphor about the stars belonging to us all?

WF:

Yes – same sky.

KR:

Do you have a cosmic and distant relationship to your work? Can you explain this idea of distance? Is this also about your own identity?

WF:

It is not cosmic – distance, in New Zealand, is a very earthbound concept. Distance is part of the story of how New Zealanders view place. It is a measure of how far away the rest of the world is from where we are – of course physically, but also in the way it has shaped our mental attitude. Aotearoa/New Zealand was the last piece of sizable land to be discovered by humans. The Polynesians found it about 900 years ago. Since then, getting here and getting away has always figured into the national psyche. Even now, when we can jet in and out, its still feels like a long way to the next place. Here’s another line from New Zealand poetry:

‘Shadow of departure; distance looks our way’.

Charles Brasch, 1948.

This line suggests that for a New Zealander, ‘distance’ can be viewed as both a positive and negative attribute. It ‘looks our way’. Isolation inhibits contact but also protects. In the virtual world it might seem that all the restrictions are removed from the flow of traffic – we can instantly share information from one side of the world to the other, but in the physical realm, distance is still very palpable – especially after a 30-hour flight to Europe when it translates as a sore arse.

KR:

Is your work a constant path to understanding your own Whakapapa? I’d like you to also tell our readers what that means, it’s very beautiful.

WF:

Whakapapa, in its most simple understanding, means ancestry. In Maori culture, who you are is a very direct consequence of who you are related to. In theory you should know your whakapapa back to Rangi and Papa (the sky father and the earth mother who created people) but whakapapa is not just a vertical understanding of genealogy, as in the European sense, it actually layers up to the future rather than descending down to the past. It also maps and binds you in a relationship with all fields of knowledge, and that holistic viewpoint shapes your world. Whakapapa is, of course, about connection to people, but also to place and objects. Objects are defined by their ancestry as well – who they were made by, and more particularly, who they have lived with. In the Maori world, objects are manifestations of ancestors.

I don’t attach the same responsibility to a personal genealogy, but I do find the ancestry of objects very interesting. Within my own practice one work begets another, and it’s also connected by a family tree to other objects made both in my own time and before. And like the Maori experience of ancestry, that interest is not only in a vertical (old to new) order, but I also have a more horizontal sense of it. Using making as the means of expression, I like observing how objects can move across time rather than just backwards or forwards. Now that sounds a bit cosmic, but it manifests very practically; I often find objects that were made eons apart capable of lining up comfortably together.

KR:

Can you tell us about your newest work?

WF:

Recently I found myself looking again at the dust-pigmented paints I used to make the work Dust (2011). That work used the dust sourced from grinding materials that I used to make pieces of jewellery with from over the past 40 years. That turned out to be over 60 different materials. Each material produced a different pigment. In my recent work, I have restricted the palette to just the dusts made by lapis lazuli, jasper, and a yellow stone called silcrete to produce the primary colours. I used these colours in a painterly way on a number of works. I also did some using the three materials in combination with each other, two strings of beads actually.

I called my recent show at Gallery Funaki (Melbourne, Australia) PRIME – for the obvious reasons relating to the colours, but it is also as an aside to the ‘primitive’ look of my work these days. There is a lot of Mid-Century feel to some of the pieces and if you invoke visual references like the totem (the bead necklaces) or the tribal fetish figure (the square faces) they are obviously influences from 20th Century art as well and as we know that story had its own complex relationship with the ‘primitive’.

KR:

And the beaded strings? It seems you’ve come back to answer a previous question of mine. How do you claim them to be from your own time?

WF:

I guess I’m playing loose with the idea of my own time. As I mentioned, their Mid-Century relationship to totem forms, so ‘my own time’ has me working through that stuff. Hopefully, not with too much nostalgia on board and with very little irony – irony being another way of riffing on the past – but more in that horizontal way I talked about with the ancestry of objects. Their ancestors are as old as any string of beads or perhaps as recent as Brancusi’s ‘Endless Column’. How long is a string of beads? Brancusi’s column was supposed to suggest endlessness but the jewellery metaphor is better – it just keeps going around and around and around……….

This article was first published in #4 Supernatural Issue of Current Obsession Magazine, 2015. You can order the issue here