Eamonn Harnett (1989) is an explorative artist who aims to grasp and simultaneously shape his life story. He does so by creating immersive artworks that reveal insights and conditions not often displayed in the art world, but every so often found in nature and indigenous tribes. His sensory and imaginative style however is rooted in the present in which so many of us seem to be adrift.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Eamonn graduated at the Gerrit Rietveld Academy in Fine Arts with an astonishing installation and performance, which he attested to the technique of Navajo sand drawing. The often skittish atmosphere of the art academy was reformed into a type of sweat lodge. Visitors were invited in a disc-shaped tent through a south-facing entrance. It was a modern design that featured a pine wood frame from which a large unbleached canvas was suspended. It housed around fifteen people at once, all who sat motionless while they watched the concentrated actions of the artist Upon entering, Eamonn carefully covered his own body with a cloth drenched in what smelled like baby oil. A human-sized steel cage, cubic with an entrance on either side, dominated the circular space. Clean white towels, a black latex blanket and a climbing rope decorated the scenery, further indicating some kind of erotic role-play. Eamonn continued the performance by preparing the surface of his sand drawing, as he walked in and out of the tent to fetch more tools needed to execute his ritual. Some of which were various highly ornamented handmade ceramic pots, a cloth (which could have been a t-shirt) and pieces of parchment-like paper. These brief moments of interruption only heightened the sense of concentration in the space filled with people who appeared dumb-struck in anticipation of what was about to happen, grounded on the somewhat sticky floor. Pigmented sands were then brought in to execute the drawing. Using fine sieves and pieces of torn parchment paper as tools, he very carefully dispersed the different natural coloured sands. He layed out various symbols around a central pattern: two rivers crossing originated by frogs; fertile grain surrounded by dragonflies; symbols which appeared to be ambiguous in nature. Not being experts in Native American signage, the viewer could be easily convinced of their originality. A set of ceramic pots, one of which contained the smell of washing powder, seemed to be similarly recreated. The energy that is drawn from the sand drawing and surrounding ritual, which is usually intended to heal or guide a single person, was shared among the few people present during the event. The personal significance and urgency of this happening reinstated by the artist truly transformed the scene that could have easily been an anthropological reenactment. Every action was as much borrowed from another culture as it was drawn from personal meaning.

Eamonn and I met after the performance and examined the clay pots he used, which he made during the year he graduated. He learned the technique from researching various Navajo and Pueblo rituals, artefacts and shelters. His approach however is quite free of their historical significance. It’s about attaining a certain language that speaks to him in his own way, producing the pots in order to gain an understanding of the materials used by the Native Americans. It seems like a very intuition-based approach but at the same time, very methodical.

While initially researching and recreating artefacts and experimenting with different shapes and designs, their intended use had yet to become clear. The ritual practice he built around the performance was a result of the direct understanding he gained from making these objects. It’s about giving them an actual purpose and personal logic, to enliven them.

Eamonn’s story isn’t that of the Native Americans, nor a typically contrived artistic one. Born in a small suburban town of Hilversum, The Netherlands, his parents’ intractable dream led the family to the township of Castlecove, Ireland. They had bought a plot of land, which was the seed of a dream that drove them to build their own home. After provisionally settling in, they cultivated the idea of becoming the local guides for visitors, leading them up into the hilly landscape and down the rocky coast and beaches. An organic farm would offer them a self-sufficient lifestyle as well as a purpose within the tiny community. They also adopted a pack of llamas that were meant to provide the company needed in such a remote place as well as to carry their lunch for their adventurous meanderings.

Before building their dream home, they erected a temporary shelter on the site. Ill-prepared, the build would last all ten years instead of the two they originally anticipated. The ‘house’ consisted of thin wooden walls that were barely strong enough to protect them against the elements that reign fiercely upon the island. As such there was very little separating Eamonn’s bedroom from the forces of nature.

This cabin was the birth place of Eamonn’s own personal mythology and a start of open-ended research about biotopic relations and connectedness. ‘In nature it is more about creating importance instead of creating meaning. Being open to engage in the relationship and an understanding of things are of vital importance, not having to become more than you are’

‘Connecting between place and place, human and place, human and human’

References of the monumental land art of Robert Smithson or the various healing rituals of Joseph Beuys all have a place in this work. Both succeed in creating alternative narratives as a means of reflection, as well as providing a necessary escape. But calling it an escape would render the work arbitrary. The work aims to show our direct relation to things around us; ‘Connecting between place and place, human and place, human and human’ as Eamonn puts it.

Connectedness is the word Eamonn uses to make sense of certain things that are not necessarily together as one. A word that carries a historical precedent in artists exploring a similar feeling of separation. For example, with the piece Eurasian Staff (1967) Beuys took upon the massive task to (re)connect two continents. A performance that saw the maker ritualistic pacing a room with a large copper rod as a ‘conductor’. Alternatively and slightly less nervous in approach, Smithson erected a land art piece named Broken Circle/ Spiral Hill (1971). He disseminates the process of erosion by displacing two pieces of land. It comes down to the basic relation between building a hill and digging in the sand, creating a lagoon. It’s a delicate yet monumental work that operates on two levels: one tells the history of the quarry where it’s located, but it also points to continuous processes that are apparent on the surface.

With an equally outlandish approach, Eamonn continues a long lineage of attempts to reconnect. The performance creates a very powerful and acute situation because it bears no signs of melancholy or reminiscence. We get the feeling he is trying to convince the viewer to ‘undisturb’ their place in nature. During his performance he touches upon normalizing sexual tension, enticing exploration and regaining balance in nature. Is it beautiful or naïve to hear when he describes art as ‘various collected logics that create rest’?

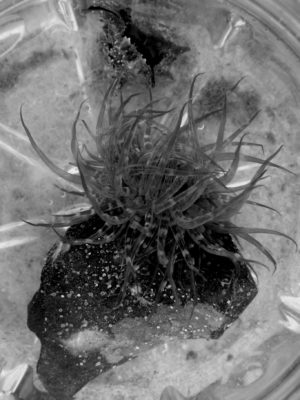

This precision in execution of the performance is similar to that of a shaman conducting a séance. The performance induces a tension, which attests to its power. It is hard to imagine the conduct of a performer who is able to deeply involve the spectator, but also nature and environment. He turns into a beacon: hovering in a moment of uncertainty, unsteadiness or transience. There is no narrative, just the sea squirts in the sea, the frog on the origin of the river and the house settling on the rock. If there is too much happening at once something shatters. The pattern, the moment, the order; it all has to be right because it is rooted on a belief which is so strongly based on life.

This article was first published in #4 Supernatural Issue, Current Obsession Magazine, 2015. You can get the issue here