Defense is one of the raw fundamentals of nature: the thorn, the native defense of plants, fulfills the same role as an animal’s horns. In French, the elephant’s tusk itself is called the ‘défense,’ easily translated to English as ‘defense:’ the act of resisting an attack. I find it quite revealing that this object carries its function within its name. How cruel it is that ivory, the elephant’s mode of defense, became precious at the expense of the elephant. The defensive element gave power to its wearer, while simultaneously announcing its vulnerability.

Along with the carved horn, humans crafted the sculpted stone and the hammered knife, which became not only tools in the kitchen drawer but objects of fetish, fantasy and symbol, objects to wear and collect. Not everyone is attracted to these shapes, quite the opposite actually. Many of us reject them and their wearers out of fear and projection, for our perceived protection. Indeed, spikes and blades speak loudly, directly to our feelings, to our guts. You don’t need to touch it to know that it hurts. You recoil without even thinking. The imagined result of its action upon the body is inherent and immediate. Thus, we fear needles and blades, the implements that cut us and draw blood. This makes sense, who wants to hurt themselves?

In my opinion, the fascination with blades lies first in the paradox of crafting something so thin yet so strong. To create a weapon capable of acting on a body, one must choose a material that will remain firm even when reduced to its bare minimum. A second paradox lies in the image of power. We learn early on that power is unstable, that it can switch hands at any time. This fragility is the main character of the blade and the spike: a knife only cuts if it is sharpened, a spike only pierces if it is honed. Essentially, they survive until they encounter a harder body. Their character is fragile by essence and violent by nature — as is, perhaps, the character of their wearer.

On one hand we have horns, thorns and spines, naturally grown forms of protection. We can find them buried in the sand like Mellie Chartres does. On the other hand, we can hone our own, distinctly human defenses. We can grind them like Marie-Caroline Locquet does from tenacious ‘archaic’ agate. We can sharpen our collars like Camille Ancelin does, so that they become weapons for social offense. We can make them shocking, as Augustin Jans does with his ironic triggers of violence.

Such weapons inspire threat and violence, but what does it imply when someone adorns their body in these symbols? What are they trying to hide behind those tusks? Perhaps, in their essence, blades and spikes carry a symbolic and material fragility.

A Means of Attracting Attention

As Armand Amato Etienne writes in the catalogue of Medusa: Jewellery and Taboo, an exhibition during last year’s Parcours Bijoux, wearing spikes is ‘a warning to others about our temperament, a means of attracting attention. Strongly symbolic, strongly arming, strongly warning.’ Wearing is showing, and when a sharp edge caresses a neck, the viewer makes an immediate association: danger! Like red, you see it immediately, and immediately it becomes a provocation. But who and what are they trying to provoke?

Camille Ancelin creates sharp, iron collars as tools against gender bias and its social entanglements. Her research began with the collar, a clothing item with nearly infinite symbolic associations. Nowadays, ‘blue-collar’ is a slang term used to refer to individuals at the bottom of a company hierarchy, particularly workers who perform undervalued manual labor. This term stands in opposition to ‘white-collar,’ which represents wealthy managers and executives. Because of its association with social hierarchy among men, the collar can be understood as a ‘masculine marking.’ By transposing this symbol onto a female wearer, with a razor-edged twist, Camille’s adornments feign and mock ‘male social success.’ If she wears a copy, is her success as valid? Her collars feign their male identity, imprisoning and subduing it for the purpose of questioning what it means to strive for success in a society dominated by unequal hierarchies.

‘by creating objects that recall violence, I release this rage that I have for social issues. This rage allows me to reflect and to create pieces that evoke violence without having to be a childish provocation.’ — Augustin Jans

Augustin Jans makes choking, ‘shocking objects’ with a point of irony: rubber barbed wires, shadows of guns and heart daggers, because they trigger an immediate response from the viewer. His work embodies a cathartic violence that answers to the social violence he witnesses: ‘sexual violence, police brutality, religious fundamentalism.’ By showcasing violence within objects, Augustin creates memorials that commemorate and demand atonement for ‘aggressions made to the individual by society.’ By recognising the political violence within intimate situations in his work, Augustin is able to remain a ‘peaceful and forgiving person’ in his own life.

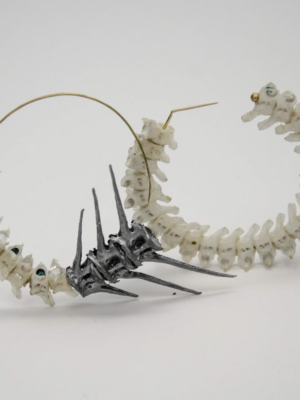

Mellie Chartres questions our love for shiny bling and the role of luxury products in justifying power and social class: ‘I like to play on the notion of seduction and luxury.’ She created her collection, Vestiges, from fish debris collected from a beach in Oman. Earrings made of fish spines and a brooch made from fish skin are made sublime by the addition of rhinestones, giving the wearer a ‘classy and luxurious look.’ The sharp spikes of the fish bones are at once repellent and enchanting — one could say the same about luxury itself.

Watch Out, Biting Dog: Compensating for the Fear of Break-down

If we can move beyond the initial aggressive feeling our gut gives us when we encounter offensive jewellery, we may ask ourselves, ‘What is behind the person wearing it? What are their intimate and maybe unconscious intentions?’ Indeed, who needs to feel power, to seem violent, to intimidate, other than those who are weak?

When I saw the brooches that Marie Caroline Locquet sculpted during her exchange in Idar-Oberstein, I immediately experienced a feeling of tension, ‘Is it gonna break? Am I gonna hurt myself?’ This was just how Marie-Caroline felt when she began working with stone: ‘With the awkwardness of the beginner, I discovered a paradoxical material. The stone I thought immutable, indestructible, was breakable [and] fragile. I started to test it; how far could I go before it broke?’ From a block of agate, Marie-Caroline carved carefully until she freed these curvy, double horns. ‘Aggressive, threatening, as if it was a defensive weapon, the translucent agate reveal[ed] its delicacy and express[ed] its hidden fragility.’ The pieces are worn on the chest, pointing violently towards one’s acquaintances. ‘The shapes respond as an echo to the wearer’s own vulnerability and weaknesses,’ Marie-Caroline explains, ‘It plays with the idea of the attraction and repulsion of the viewer. Jewellery communicates a part of ourselves, it can be a cathartic embodiment for the one making it.’

Augustin Jans places himself as a vector, processing violent action into object creation: ‘by creating objects that recall violence, I release this rage that I have for social issues. This rage allows me to reflect and to create pieces that evoke violence without having to be a childish provocation.’ He processes his anxieties through creation, meeting violence with violence of a kinder sort. In answering social violence with cathartic violence, Augustin works to overcome his fear of break-down.

In contrast, Mellie Chartres aims to remove the threatening character of the fish’s natural defenses and enhance their subtle fragility: ‘My jewels lie to us, they speak of illusion, of suggestion […] I like the fragile side and the delicacy that the object reflects. I find that there is an aggressive side with these sharp edges which is mitigated by the round shape of a creole [hoop] that I gave him.’

As makers of blades and spikes, we often aim to externalise a feeling through the materialisation of an object. As wearers, we aim to externalise our feelings through ornamentation of our social bodies. In both of these processes, there is a risk of bodily and social harm: do you have the guts to put these jewels on?

Approval of the Viewer, Consent of the Wearer

Not everyone is willing to wear a piece that might hurt them or others. So why, then, will some stand for this threat, or even seek it out?

Marie-Caroline knows that her brooches may create distance: ‘Some people can feel uncomfortable, even scared to wear [them],’ she recognises, ‘it is not something that leaves viewers indifferent. The wearer has to take charge of the piece, to assume it, to appropriate it. You can’t hug without causing a strange feeling to the other [person]. This is, therefore, not an easy piece to wear.’

A pair of earrings presents a different threat than a brooch: you might hurt yourself as well as others. As Mellie Chartres explains, ‘I found it interesting to use these thorny shapes to make earrings. Indeed, they are close to the neck and prick it. There is a worrying side to it. But I think that wearing jewellery that we like and that [enhances] us is a way to gain self-confidence, to feel good about yourself.’ With repellant means, Mellie gives us a lesson in positivity.

Looking Fierce, Willing to Seduce

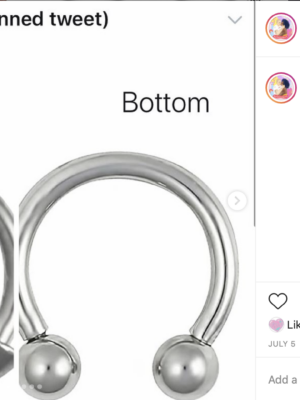

While scrolling through Instagram I found a post from @hotmessbian showcasing two different types of piercings: on the left a piercing with a spiky ending labeled ‘top,’ on the right one with a round ending labeled ‘bottom.’ This reminded me of a basic rule: whoever has the weapon controls the game. Perhaps these bladed adornments also enforce the rules of seduction?

In Camille Ancelin’s work, the rules are reshuffled. Her collars ‘lead to a kind of voluntary servitude on the part of their wearers. Decorating oneself with the collar induces a real change in the person’s appearance, forcing them to play a character they are not. Apart from the social codes conveyed by the collar’s signage, the object itself implies a codified attitude.’

I asked Augustin as well, whether he thought that the wearer could embrace sexual power by wearing his pieces. ‘I hope so!’ he said, ‘I have the will to make objects which invite the revendication of oneself, of one’s body and of one’s personality. Be yourself, and let the others fuck themselves.’

The symbolic meanings of the blade and the spike in jewellery are manyfold. They are tools for fighting social bias, overcoming our anxieties and appreciating fragility. When their violence is embraced, they encourage the wearer to take control of their body and their situation. When their violent nature is reduced, these symbols of harm encourage creator, wearer and viewer alike to stand firm without denying our fears. Like the elephant, our blades and spikes make us fearsome, but we can choose when to bare our fangs and when to encounter each other with delicacy.

This article was published on occasion of Parcours Bijoux 2020 and commissioned by Current Obsession and Parcours Biojoux

Check out the ultra-edgy work of these four young artists from Parcours Bijoux 2020

Camille Ancelin (Grad 2016, HEAR Strasbourg): Point d’interrogation (Question Mark) by Collectif Viv – Vitrines de la rue Cadet, Rue Cadet, 75009 Paris

Mellie Chartres (Grad 2018): Point d’interrogation (Question Mark) by Collectif Viv – Vitrines de la rue Cadet, Rue Cadet, 75009 Paris

Augustin Jans (Grad 2020, HEAR Starsbourg): Point d’interrogation (Question Mark) by Collectif Viv – Vitrines de la rue Cadet, Rue Cadet, 75009 Paris

Marie-Caroline Locquet (Grad 2021, HEAR Strasbourg): Entrée de Jeu! (Right from the Start) by POP Atelier Bijou, ENSA Limoges – Galerie Julio Artist Run Space 75013 Paris