With the hope that the Statdmuseum can reopen its doors soon, Current Obsession felt it important to shed some light on this joint project while we’re waiting. The following interview with Münchner Stadtmuseum curator Antonia Voit and Prof. Karen Pontoppidan reveals how both students and the curators reflected on the past to create a fresh, contemporary show. In the context of our current historical moment, rife with fresh challenges, Pontoppidan’s belief that the exhibition should be seen as an object-based analysis of postmodernity gains special relevance.

Nina Moog: Could you describe how the collaboration between the Münchner Stadtmuseum and Karen Pontoppidan’s students began?

Curator Antonia Voit: The occasion for the Münchner Stadtmuseum to conceive the exhibition MUC/Schmuck was based on the acquisition of a private collection of jewellery pieces from Munich, assembled over several decades by art historian Dr. Beate Dry-von Zezschwitz. The collection comprises almost 200 pieces of jewellery, with a chronological focus ranging from the 1880s to the 1930s. The earliest pieces in the collection were created at the end of the 19th century, when Munich developed into a centre for goldsmiths. While studying the Dry-von Zezschwitz collection, we found it exciting to see which themes and ideas occupied Munich-based jewellery artists at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. We quickly became interested in the question of how these themes are still relevant for young jewellery artists today, which is why we contacted Prof. Karen Pontoppidan and asked whether she and her class would be interested in a joint exhibition project.

Prof. Karen Pontopiddan: The students and I cooperated for a year with the curators from the museum in order to develop an approach relevant for all involved. From my point of view as an educator, I find it crucial for the students to look upon the subjects of their work, not only as an individual expression of interest, but also as a cultural phenomenon. This exhibition-project offered such a perspective. The curators at the museum were very open towards the ideas of the students, however bigger decisions such as the exhibition architecture, were made by the museum.

NM: How were the final pieces selected for the exhibition?

AV: Before we talked directly with the students about their work and the historical work, we asked them to explain in writing why they came to Munich to study, what themes they deal with in their work, what meaning historical styles and techniques have for them, and to what extent nature is a source of inspiration for them. The answers we received were very fruitful and informative for us. They also strengthened our desire to conceive this exhibition together. During the personal exchange with the students it wasn’t an easy task to name concrete themes that would do justice to both historical and contemporary jewellery.

In consultation with one another, we ultimately decided to base the selection of the themes primarily on historical jewellery, which would allow the students to respond with their own work. After a lengthy exchange of ideas, the final selection of pieces was chosen equally – the historical pieces by the curatorial team of the Münchner Stadtmuseum, and the contemporary pieces by Prof. Pontoppidan.

NM: What effect is achieved by mixing contemporary jewellery with historical art from the Münchner Stadtmuseum?

KP: At the first glance, the concept of the exhibition MUC/Schmuck might seem a bit stale; as often is the case, most of the historical pieces look rather familiar and most of the contemporary pieces look rather outlandish in comparison. The relevance of this exhibition project becomes evident when the parameters are framed as a comparison of pieces that express modernity against pieces that express the postmodern condition. Postmodernity is sometimes difficult to comprehend, since it is defined as a reaction towards modernity. Therefore, it is a helpful tool to compare current culture to cultural movements of the 19th century. This has happened within architecture, sculpture, literature, but to my awareness not thoroughly within the field of Contemporary Jewellery.

AV: It surprised both of us, and the jewellery class at the Academy, just how well the combination of the historical and contemporary jewellery worked within the different themes. Not only do they coexist easily, but the combination also allows the respective social frameworks and artistic intentions to emerge much more clearly. An example of this are the two crabs that can be seen in the exhibition theme ‘Natures’, which forms a central chapter of the exhibition.

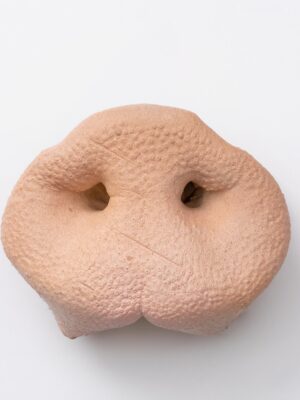

The two-dimensional brooch made of silver in the shape of a crab, designed by Carl Cosmus in 1908, has been paired with the brooch Der Nase nach by Patrik Graf, created in 2018, which also depicts a crab. While nature was a source of inspiration for artists of the Art Nouveau period, through which they hoped to find their own new formal language, today’s students reflect a different concept of nature, one that has been expanded to include social aspects. For example, Graf’s piece addresses environmental problems by using processed plastic waste from the sea.

KP: The works of the students are reactions on these timeless subjects, which create a compelling visual comparison and serve as surface fabric for the underlying discourse. With each theme a twofold question is raised: how was the subject perceived within the historical timeframe and how is it perceived today? What we see throughout the exhibition is therefore the spirit of the different times; the examination of modernity often reveals notions like positivism, progress, the achievements of man, the ideal, authenticity and authority. On the other hand, the contemporary pieces demonstrate a critical attitude towards all of the above and promote relativity, plurality and diversity.

I’ll give some examples. Dealing with a theme like ivory, issues of wildlife protection comes to mind, which can easily turn into condemning the deeds of the people in the past. Through the comparison of ivory with the materials used in the contemporary pieces, for example animal fat, the complexity of the subject surfaces more clearly. It questions the reasoning for using ivory in the past, as well as the reasoning of how today’s culture uses animals. In short, the discrepancy between the materials of the past and present becomes so obvious that it hopefully starts to generate critical thinking. The theme ‘Influences from Distant Lands’ is also an interesting category for this line of thought. A particular attitude towards foreign cultures, and a consuming approach towards symbols originating from a different context, becomes visible in the historic pieces. This problematic attitude is, however, still present in today’s globalized world, and therefore needs to be examined through a critical lens, both in past and present times. In short, although today we recognize cultural appropriation as problematic, we seldom recognize the extent to which it is interwoven into our own culture.

NM: I’d love to conclude with some perspective on the holdings of the museum collection. 19th century jewellery art in Munich is known for its assimilation and revival of historical styles and techniques. Why do you think there was such a fascination with techniques from, for example, the Bronze Age or the Renaissance?

AV: Yes, Munich was a centre of historicism. In 1897, an observer noted that especially Munich arts and crafts played the leading role in Germany in the last decades of the remaking of old styles. A significant contribution to this was certainly made by the King Ludwig II’s numerous commissions, which were based on past styles and certainly made a significant contribution.

Conversely, the master Fritz von Miller was formative for goldsmiths art from 1868 to 1912, first as a teacher and later as a professor for metalwork at the Munich School of Applied Arts. He shaped a climate in Munich that made it possible for the craftsmen working here, even after the emergence of Art Nouveau, to take an unconcerned interest in historical styles and techniques.

Renaissance style was increasingly brought into focus at the large art and craft exhibition by the Bavarian Arts and Crafts Association in 1876. In addition to contemporary works, historical works from the Romanesque period to the 18th century were shown under the title Unserer Väter Werke (The Works of our Fathers). As a result of this exhibition, the jewellery stores of Munich filled up with neo-Renaissance jewelry.

At the end of the 1880s, Rococo came back into fashion, which is illustrated in the MUC/Schmuck exhibition via brooches with putti motifs by Karl Rothmüller and Theodor Schallmayer. From about 1907, Munich goldsmiths like Adolf von Mayrhofer and Max Strobl were concerned with early historical forms and ornaments, especially the spiral motif, as it has been handed down from the from the Bronze Age. It aroused their interest and inspired their designs for jewellery and utensils. These works were not copies of historical models, but a reference to bronze-age jewellery that simultaneously demonstrated a modern taste for simplicity and originality.

Interviews were carried out separately, in both German and English. They were combined and shortened for this feature.

Credits: The curators at the Münchner Stadtmuseum are Jutta Hofmann-Beck, Konstantin Lannert, Antonia Voit. Exhibition design/architecture was made by CPWH – Caroline Perret, Winston Hampel. Graphic design was done by Wiegand von Hartmann.s