Laid out on the table beside us were several silver necklaces, which displayed Gerd’s thumbprint cast on one side of oblong shaped pieces of silver. Gerd told me that he had taken out the pieces in preparation for an upcoming May exhibition of his work in Hudson, New York. He wanted to get a good look at the work, and determine what was missing. These pieces are part of his most recent series Mit meinem Daumen modelliert (Modelled By My Own Thumb, 2020.) One of the necklaces looked familiar. I’d seen it a week before, when I visited Gerd’s underground studio, which is located a few minutes walk from his home. At the time, he had energetically picked up the piece from a worktable and swiftly fastened the necklace around my neck. Due to the fixture on the back, he told me that if I were to walk around the atelier, the necklace would twist and turn with the movement of my body. At first, he had been unsure about this twisting effect, but then realised it allowed for both his thumbprint and the opposing smooth, silver surface to be revealed. In the end, this pleased him. Gerd told me that it’s hard to assess a piece without it being worn; that jewellery, like an actor, requires its own stage. He’s therefore decidedly of the school that believes that jewellery belongs on the body. When I noted the way in which intimacy can be quickly established when you allow someone else to fasten a necklace around your neck, Gerd nodded. He told me that he often hears that a necklace is really beautiful, but it’s ‘not for me.’ If he takes the necklace and places it around the neck of a person, there’s awe and surprise on the part of the wearer. Suddenly, the necklace has a new context: both piece and person have transformed. An interaction has taken place.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

During our conversation, Gerd would often think of something, and energetically spring up from the table to quickly retrieve an example of what he was talking about. Now, he brought out a catalogue of the open-air museum Storm King Art Center in New York. We both marvelled at the project’s scope, which includes the largest collection of outdoor sculptures from Alexander Calder to Richard Serra. Flipping through the pages, Gerd took his time. He’d pulled the catalogue because the idea behind his most recent series emerged from a piece he made in homage to the late Peter Stern, a New York art collector and the founder of Storm King. The two men were friends, and after his death, Gerd decided to make a silver collar with colour pigments in a work entitled Modelliert mit dem Daumen von Peter Stern (Modelled With the Thumb of Peter Stern, 2019). The ridges of a fingerprint, where the print is different with each person, provides a natural grip for colour pigment, allowing Gerd to experiment with colour.

‘He told me that he often hears that a necklace is really beautiful, but it’s ‘not for me.’ If he takes the necklace and places it around the neck of a person, there’s awe and surprise on the part of the wearer. Suddenly, the necklace has a new context: both piece and person have transformed .’

Despite his passing, the silicon mould of Stern’s thumb was ready because Gerd had made a prior piece for him using his thumbprint. Gerd always saves the fingerprint moulds he makes, and now holds an extensive archive containing hundreds. He told me that in order to make a good piece of jewellery, you need something new, a strong idea you can hold onto. He thought he maybe had it with this latest series, but only time would tell. Through its origins as an homage, the series also gestures to Gerd’s historical position within the field of Contemporary Jewellery. Gerd knew Peter Stern through the well-known art and jewellery collector Helen Drutt. Her former Philadelphia gallery was one of Gerd’s first contacts in the United States, partially responsible for widening the goldsmith’s influence abroad.

Our conversation meandered away from his contemporary work to Gerd’s beginnings in jewellery. Gerd told me that he ‘started to make jewellery and there was no substantial reason for it. I just slipped into it. There’s no one in my family that makes jewellery.’ He described to me what has been published elsewhere, how he came to Munich to visit Hermann Jünger in the mid 1960’s after he saw Jünger’s work in a newspaper. The pieces were so new, and Gerd was filled with a strong desire to go and work in his workshop. After hitchhiking to Munich, Gerd rang Jünger’s doorbell and informed him that he wanted to work for him. He recalled that kids were running around within a fairly chaotic atmosphere. Jünger asked Gerd, then in his early twenties, if he could also babysit. Gerd immediately said yes. When asked how much money he wanted to earn in exchange for his work and babysitting, Gerd named a really low price in an attempt to ensure his employment. At some point, his salary was raised. After a years time, Gerd decided to open his own studio but maintained a relationship with Jünger.

In 1972, Gerd travelled to the fifth Documenta show in Kassel and visited an exhibition created by the Swiss artist and curator Harald Szeemann (1933-2005). For Gerd, this show was ‘completely revolutionary.’ Often cited as the first time that ‘outsider art’ was represented publicly, the exhibition included replicas of Adolf Wölfi’s (1864-1930) hospital room as well as books and other objects from the Waldau Psychiatry Collection near Bern. The impact of seeing these so-called ‘private mythologies,’ which reveal an identity of the depiction and the pictured, stayed with Gerd. The pieces exposed a fresh example of how people made art as a means to show their own world experience. For Gerd, the show captured something independent of an art movement, something that felt ‘open’ to him. He felt energised. Around the same time period, Gerd discovered the artwork of American artist Bruce Nauman through magazines and catalogues. Gerd told me he felt like, ‘wow, ok, there is something new happening in the world. But I had a problem since my interest wasn’t in making art, but in creating jewellery.’ After the show, he returned to Munich and wondered, ’what can I do to work at the level of this exhibition?‘ He then started to think about the body.

Gerd’s gold and silver body casts from the 1970s are well known in part because they are emblematic of a historical boundary blurring in Munich, where previous definitions of what had been considered jewellery were called into question. During this period, Gerd briefly considered repositioning himself as a sculptor, but a good friend talked him out of it, for which he’s grateful. (When I asked him why, he simply replied ‘I’m a goldsmith’). His body casts are beautiful, and arguably contain a surreal, playful aftertaste. Paging through Gerd’s Werkverzeichnis 1967 until 2008, an epic monograph which depicts the extensive reservoir of his work, I paused at a few pieces that celebrate this interest. In 1982, Gerd made a video entitled 60 Ringe in 60 Sekunden, (60 Rings in 60 Seconds.) Aptly titled, the film is one minute of Gerd jamming brass curtain rings on and off of his hands at a manic pace. He practiced over a week so that he would be able to do so fast enough, using a stopwatch to time himself. On the same page in his monograph, the piece Gold Unter Meinem Fingernägeln (Gold Underneath My Fingernails, 1983) is depicted. When I asked Gerd about it, he told me that goldsmiths work with gold and therefore it’s possible that gold dust comes to rest under your fingernails. ‘The black under your fingernails is dirt, but it could be gold instead of dirt. That’s the idea.’ The piece itself is composed of ten little half moons you could push under your fingernails. He told me that he also made another piece, Sechster Finger (Sixth Finger, 1978) which aims to play with the questions posed by the body. For him, these pieces ‘turn themselves a little away from jewellery.’

Gerd told me about another piece, based upon the form fingers make while clutching a ball of wax, entitled Zwischen den Fingern (Between the Fingers, 1980), made of cast tin. This last piece interested him because of what it reveals about the way we act with jewellery, even with pieces that may not seem wearable at first glance. ‘You don’t,’ he told me, ‘just spread your fingers and let the piece fall to the ground.’ While watching someone wear this piece for a whole evening, Gerd had witnessed how she made little adjustments with her hands to keep the piece in place, but never allowed it clatter to the ground. ‘It’s just like a handbag stays in your hand. You don’t randomly drop it,’ he pointed out; ‘with this piece of work, you just hold it.’ Gerd is fascinated by the fact that there are things that you just don’t do, that introducing something to the body can allow for its acceptance as fact. ‘There are things and they are just there, and the person finds it self evident and doesn’t even think about it.’ He gave another example, that of pimples. We don’t just scratch open pimples in public. This idea was really interesting to him. Our conversation then turned to cell phones – how they are always in our hands, operating as new extensions of our bodies. Gerd told me that he thought it was wonderful, the cell phone and its heaviness in the hand. He liked watching how people text with their fingers in the underground, and how they handle their cell phones in frenzied texting sprees.

When I noted my interest in his work which relates to a certain humour, Gerd opened an elongated, red box and dropped a necklace on the table. ‘This necklace actually has something very conventional. There’s the chain, and then the ‘beads’, and then the chain again. But I thought, they shouldn’t be beads but chewed up chewing gum cast in gold.’ I imagined Gerd sitting somewhere on a park bench, stuffing one chewing gum after another in his mouth. Or did he gather chewing gum chewed up by other people, friends? Gerd chewed them himself, collected them in a box, and then sent them off to Pforzheim, a city on the edge of the Black Forest. Making the necklace, however, was no easy task. The casters called back and informed him they wouldn’t, in fact, be casting his chewing gum. ‘They told me, it’s not aesthetic.’ He eventually changed their mind by telling them, ‘listen, this is going to be in a museum!’ This piece felt a little different to me than his other work, which is so directly connected to the human body, but Gerd saw a connection. He likes to work with what is ‘vorhanden,’ or what is available to him. What happened by accident, he noted, is that the chewing gum pieces cast in gold ended up looking like gold nuggets. The way in which the piece could shift meaning appealed to Gerd, and he appreciated the possible dual interpretation of those lumps of gold.

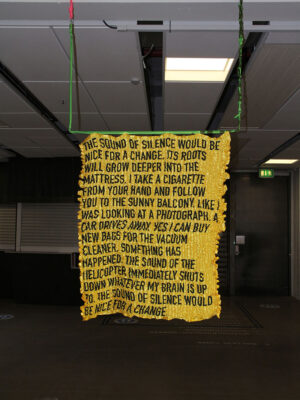

An interest in shifting meanings equally applies to an interest in wordplay. Gerd collects phrases involving reference to gold. The German phrase ‘Sich eine goldene Nase verdienen,’ cannot really be translated directly into English, but translated literally it means ‘to have earned a golden nose.’ Its meaning is, indirectly, meant to indicate a successful person. He told me, however, that the search for gold within language is limited. There isn’t much to find. I suddenly thought of the Italian goodnight expression ‘sogni d’oro,’ which means ‘dreams of gold.’ Gerd lifted his eyebrows, ‘oh, good one,’ and then quickly wrote it down in his notebook. He keeps written recollections of his experiences in his work. Some of these were previously published in his aforementioned monograph Werkverzeichnis. Gerd plans to update the monograph to include the work he’s produced in the last decade, and has therefore been collecting new writing. He showed me a few pages of these tiny vignettes. Within the space of two or three sentences, these spare narratives hold a mythic, fable-like quality.

Here are a few of my favourites:

The husband of C. passed away very young. She asked me what I could make out of her wedding ring. The ring was heavy and made of pure gold. I made the ring larger and larger until finally her hand could slip through it. She said: now I have ‘him,’ around my wrist.

G.E., an older lady, had eleven grandchildren and thirteen great grandchildren. I was fascinated. I made a necklace with the names and birthdates. Very moved, the client told me ‘now I have all my grandchildren and great grandchildren around my neck and when I can’t remember a name, I can look it up!’

Her tendency was for a bracelet. But she gave herself time. She looked at it, tried it on, looked again. Gradually it became clear, what the bracelet did to her. It grew dominant and compelling. The bracelet had waited for her.

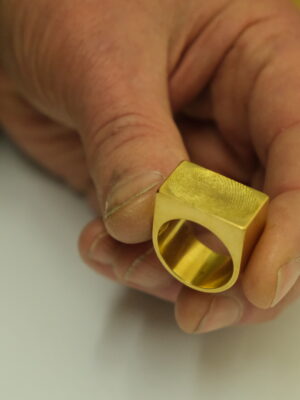

These short bursts of storytelling speak to where Gerd lays his focus; the importance of his work is linked to individual people and his interactions with them. Yet the charming atmosphere and whiff of nostalgia they convey may not always apply to his actual jewellery. Carefully placed in stacked boxes, golden impressions of skin and bone can trigger an impression of the macabre. Out of a small box, Gerd took out a ring and handed it to me. It was a cast of the piece of skin that the ring itself covered when worn: gold ‘skin’ replacing the skin beneath it. For him, this piece demonstrates how a finger, cast from gold and worn on the original finger can become jewellery. The idea has a purity to it. It’s simple. His work is often based upon an act of duplication: an interest in creating a wearable impression of the body on the body. His work implies that there can’t be a more potent definition of an individual than the cast taken from that individual. When that cast is taken from a person, and handed to another, it creates new meaning. It’s interesting to him when this exchange can perform well and when it cannot. ‘If this ring was the skin of another person, like her boyfriend or something,’ he told me, ‘then it could be macabre. If it’s your own finger, the piece becomes possible.’

Gerd took another piece out of a carefully labelled box, and I felt a jolt. Von Ihm für Sie (From Him for Her, 1990) is a wide, hinged bracelet made of a male wrist cast in gold. Alongside the clear cast of veins, the protruding bump of the wrist bone grants the cast its special shape. Inspected at close range, tiny, individual pores on the skin are visible. This piece came to life for an architect friend that Gerd often made jewellery for. He was asked to make something for the architect’s wife, and was granted time and support to make it. After a while, an idea came to him. “I told him, ‘we’ll take your wrist and form it, and then we’ll take it off, we’ll pour it into metal and she will then wear it as a bracelet. So this is his wrist for her.” Gerd explained that the husband had a bigger wrist, and because the woman was quite small, the bracelet fit her exactly. I asked if the process of making the mould rips away the arm hair, if it’s painful. Gerd laughed. ‘Naturally,’ he told me. Gerd is often asked how many pieces exist of a given work. When he creates a commission, like in this case, Gerd makes a duplicate for himself to keep it in his archive. Should a piece be requested by a museum, then a third piece comes into the world.

‘There isn’t life and work,’ Gerd told me, ‘it’s always one and the same.’

Towards the end of our conversation, I showed Gerd some work from the jeweller Jo Harrison Hall. A recent graduate from Central Saint Martins, her pieces also draw from the body, in exploration of hygiene as ritual. Her material is not focused on metals; she incorporates materials she associates with hygiene. Some pieces, hand carved from soapstone hold resemblance to one of Gerd’s pieces, Grosser Faustkeil (Big Arrowhead, 1980.) To make this piece, Gerd clenched a wax ball and then cast the remaining relief, generating a negative form of his knuckles and cast it in tin. After scrolling through her Instagram together, Gerd told me that when he looks at such pieces, he feels reminded of the dangers of a contemporary art school system which encourages artists to exhibit early and frequently, often before they’re ready to show work. Gerd believes in craft, in a necessary training period and the implied adherence to the guidance of a master. He does see, however, connections between his work and younger designers. Gerd told me about a recent print from the fashion house Schiaparelli. Creative designer Daniel Roseberry has marked the 1930’s Schiaparelli ‘signature’ with his own use of fingerprints. Gerd particularly liked a fabric pattern where a fingerprint had been reproduced, covering a white suit in organised rows for the Fall-Winter 2020 collection. He wanted to show me a photo, so we walked together into the small office leading off of his kitchen.

Gerd clicked open a file on his computer. Allegedly, Elsa Schiaparelli was one of the first designers to authenticate her designs, putting her fingerprints on the tags of clothes to avoid being copied. Gerd sees his own thumbprint as an insignia, akin to a crest or seal. When showing me Mit meinem Daumen modelliert (Modelled By My Own Thumb, 2020), he told me, ‘I am the artist. I am the creator of the piece. Therefore, the work is stamped with my thumb.’ As we looked at the Schiaparelli suit, light seeped into the room through a window, under which a large gun lay on the windowsill. I told him guns, even toy guns, frighten me. He jauntily picked it up and handed it to me, as if to assure me it wasn’t real. (It wasn’t, but had a certain heft.) Gerd’s art gun, a gift from a friend, stays under the window to dissuade unwelcome visitors. He told me, ‘maybe a thief will peek in, see the gun, and get frightened away.’ We both cackled.

A few encounters and swift telephone calls here and there aren’t enough to get to know someone, but my sense was that Gerd is someone with a sharp sense of humour. Hinting at a love for play, Gerd’s long-held impulse to make a gold and silver crown without commission links to his desire to create. He told me, ‘you develop an interest, and you do it because you enjoy doing it. The idea develops over time. Finally, you get somewhere where you can show someone something, and that’s another step. But when you show a piece to someone, it already has a form.’ Gerd always wanted to make a crown. One day, around 2008, he finally had time to spare as well as a bit of extra money. When the crown was done and lying on the table, his desire suddenly felt absurd. He asked himself, ‘what’s the point of this? What does it serve other than my own private wish to make a crown? It has nothing to do with the contemporary moment.’ He felt that if he showed it to someone they would think, ‘what does he want with a crown today? The world has different problems.’ He didn’t know what he wanted to do with it.

Finally, Gerd came up with the idea of taking photographs of friends and family. The piece then had a new meaning, a way to generate a collaborative photographic work that also served as a record of his visitors. Entitled Sie Besuchten mich und Krönten sich (They Visited Me and Crowned Themselves, 2015), today these photographs live in a manila folder. The images usually show two people, where one is in the process of being crowned by the other. Gerd instructed his visitors how to stand, and what position to take. The photographs were all taken in his home; this is no crown that knows the rush of travel. As we looked through the photographs, I asked him how he knows when a project ends, or a series is complete. Now, he told me, ‘I took three hundred photos, three hundred and fifty photos. I was done. Your interest ends, in a very natural form. Then it’s over.’

Late in the day, Gerd and I were tired of talking. I’d had more than my share of Darjeeling, and the sky outside the windows had darkened. It was time for me to go home. Before I left, Gerd told me he had recently read an interview by Raymond Pettibon, an artist in part known for his connection to Sonic Youth. He rummaged through his CDs, and grabbed Goo (1990). He walked over to the table, sliding out the album insert to show me Pettibon’s cover art: a black and white image of two sunglass-wearing mods. I resisted a brief urge to rifle through the rest of his CDs. ‘Pettibon was really integrated with Sonic Youth, and very much in the scene,’ he told me. He had sprung upon Pettibon because I had asked him a banal question about his routine, his division of work and play. Gerd had thought of Pettibon because the artist had mixed the two, integrating work and life as an indiscernible whole.

‘There isn’t life and work,’ Gerd told me. ‘It’s always one and the same’. Was he sure that was healthy? Ostensibly, such attitudes imply that you’re always working. He told me, sternly,‘ but it’s not just working, it’s also living.’ I told him that I need pure relaxation time because I am, after all, living in Europe for a reason. He told me that working was also a form of relaxation, but he assured me he has down time outside of his atelier. He visits museums, meets a friend for a beer. These are also the moments when the global pandemic slithers up from behind him to interfere in his life. Other than that, the rhythms of his week are much the same as a year ago. ‘What I certainly don’t do,’ Gerd clarified, ‘is lie down on the beach and tan. That’s not my thing.’ I pulled on my shoes, and clomped down the stairs from his apartment down to the Frauenhoferstrasse. I haven’t listened to Sonic Youth for a long time. When I got home, I flipped through the pages of Gerd’s Werkverzeichnis and stopped to pause on a page of his well-known body casts: a nose on a nose, the ears of silver, the golden Achilles heel. Kim Gordon crooned in the background, and the pieces suddenly looked punk. I turned up the music, and I let it rip through my apartment out into the quiet streets of Munich.

This interview was conducted in German and translated into English.

Nina Moog is a writer and director of photography. She lives between Munich and Rome. She would like to make a radical statement against bios.

nm.moog@gmail.com