A few blocks away, the words Dziuba Jewels are emblazoned above the entrance to Gabi’s studio and showroom, underlined by a glowing, fluorescent tube. On an inner doorframe, scraps of paper hang face down, waiting to be taped to the glass door in case she needs to run out. ‘Getting my glasses!’ one note exclaims, followed by Gabi’s phone number. She tells me that these remind her of the away messages Holly Golightly has in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. We enter the street facing showroom, designed by the Austrian artist Heimo Zobernig. Across the room, a dark Hans-Jörg Mayer painting hangs mid-air by way of a linked metal chain. Duck behind it, and Gabi’s jewellery work bench and desk are revealed.

We flip through a catalog, and pause on a white-gold necklace she designed for a DeBeers compe-tition in 1976, its diamonds embedded towards the end of a poetic squiggle. Gabi designed the piece while studying in Pforzheim, where she attended the Fachhochschule für Gestaltung under Reinhold Reiling from 1972-78. One of her classmates was the jeweler Manfred Bischoff, and the two of them shared a beautiful, Altbau apartment. In love, Gabi painted the entire kitchen gold. Neck craned skywards for days, she transformed the ceiling into a fantasy landscape where Wiener Schnitzel danced beside grapes and farmyard chickens. In 1976, the duo spent three months in London, stumbling upon what would become an unforgettable, beloved experience for both of them: The Rocky Horror Picture Show. They strolled past storefronts wrapped in packing paper, ‘not sure what to make of it all’ but utterly entranced. Despite their shared aesthetic worlds, Gabi and Manfred’s tastes in music and art differed. She loved ACDC, The Sex Pistols, and Violent Femmes, while Manfred found some of these influences a little low-brow. ‘He liked finer things’, she tells me. ‘His tastes were always a little more sophisticated than mine.’ Back then, one of Ga-bi’s favorite songs was Ian Dury’s Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll. She shows me a small sculptural piece Manfred made for her: a miniature Dury with ‘Sweet Gene Vincent’ spouting from his lips, words written through sweet metal twists.

After graduating Pforzheim, Gabi and Manfred hoped to study under Hermann Jünger at the Aka-demie Der Bildenden Künste in Munich. Early on, Gabi realized that a commercial jewellery path wasn’t in her future. As part of her degree, she had interned at a commercial factory that made samples for mass production and a goldsmith asked her to make some small cufflinks. ‘I thought to myself, I can’t make such tiny cufflinks. I don’t know how do that at all. So I just made them much, much bigger.’ (The goldsmith almost fell off his chair when he saw them.) During her ad-missions interview, Jünger asked Gabi: ‘What will you do if I accept Manfred, and not you?’ Within the year, however, they were both studying in Munich together.

As an instructor, Jünger emphasized the importance of materials and craftsmanship. Back then, Gabi preferred to work with silver or metal alternatives, like wood. She pulls out a three piece wooden brooch from 1981. I hold it in my hand, surprised by its heft. ‘In Munich, some of us were reclaiming seemingly worthless material,’ she explains. She painstakingly covered the wood, which originated from decorative moldings, in a striking yellow lacquer. ‘Gold was considered bourgeois,’ she tells me. ‘And it didn’t quite fit with the times.’ Despite this, Gabi also made a se-ries of elegant, gold safety pins. Today, she still wears one and uses it to pin together the top of her shirt. Gabi places the pin onto the flat surface of the table, and I see that it’s slightly bent, the result of repeated repairs. She tells me, full of humor, that easy access to gold is one of the few luxuries afforded to goldsmiths. (Privately, I reflect that meeting iconic goldsmiths mid-week is one of the few luxuries of freelance writing.) Originally, this pin was one of seven, and the one on the table is the remaining survivor. Lost or found, a golden safety pin emanates a simple and beautiful extrava-gance. ‘What did Truman Capote say?’ Gabi reflects.“‘I may be a black sheep, but my hooves are made of gold”.’ She pauses. ‘Or whatever.’

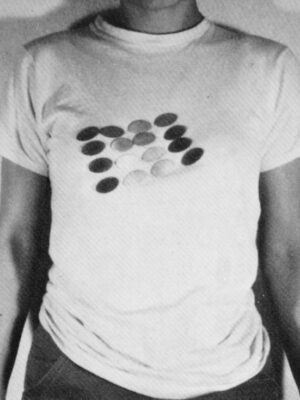

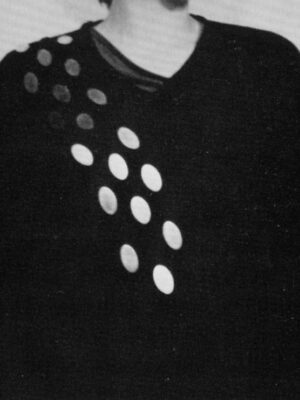

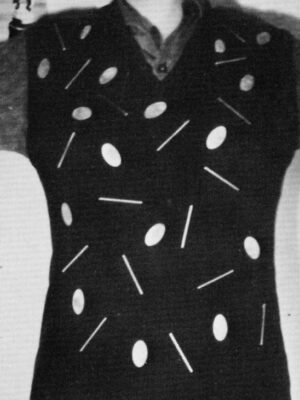

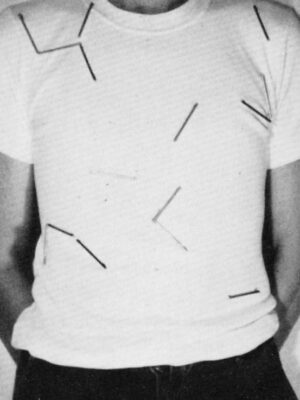

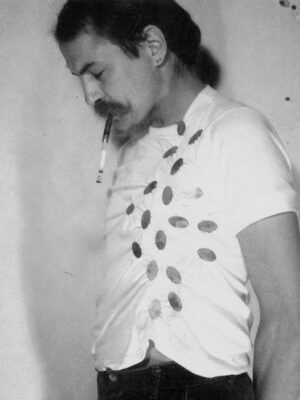

As we talk, Gabi quotes lyrics and texts of unreal lengths from memory, and she seems to find par-ticular joy in the images that words can evoke. After attending an Andy Warhol exhibition in Stuttgart during the late 1970’s, she kept the catalogue. Gabi slowly turns its pages, delighting in Warhol’s verbal playfulness. ‘Look, here’s a Golden Birthday Shoe, or here’s one called Shoe with Strawberries.’ Back then, Gabi admired how Warhol’s hand-drawn shoes were covered in gold foil, appliqué style. It was decorative, and she hadn’t seen anything like it before. Warhol might have approved of Gabi’s 1979 Lenbachhaus show Körper-Zeichen, where she displayed polaroids of her work worn by friends. To take the photographs, Gabi placed a pile of gold-plated oval and tubular copper brooches on a table, instructing friends to wear them as they chose. She then put her models up against a wall, and snapped. The artist Thomas Kammerl created a pattern, tucking the oval brooches under a sweater, Manfred Bischoff spelled out MY WAY, and Waltraut Reis arranged the ovals over her breast. At the time, Gabi wasn’t interested in making single brooches but focussed instead on the concept of multiples in combination with the free participation of the wearer.

During our time together, I got the sense that Gabi’s aesthetic has always been influenced by music. After failing her final year of high school, an experience she credits as key to the devel-opment of her taste, her parents placed her under house arrest. While they may have been under the (false) illusion that she was studying, Gabi listened all day to the radio. ‘It’s also how I learned French’, she tells me, spouting off a few phrases as if in proof. In the mid 1980’s, Gabi was the singer in a six-person ‘psychedelic band’ called Die Schlüssel (The Keys in German.) They were ‘an answer to The Doors.’Gabi leans back in her chair and recites from memory: ‘Eyelashes whisper on asphalt roads, his jeans are super tight! He drives a Ford Mustang, his pockets full of dope. Oh baby, baby! Take me with you!’ Wearing a black miniskirt, Gabi would stand on stage and read directly from a typewritten page, often unable to make out the text because the clubs were so dark. On one recording, you can hear Gabi request the venue to please turn on some lights.

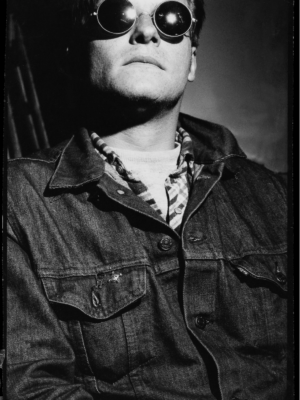

Drawing inspiration from Beatles’ Apple Corps, Die Schlüssel created a so-called Schlüs-selproduktion (Key Productions), making key-inspired costume jewellery. In a black and white photograph of the painter and Die Schlüssel founder Hans-Jörg Mayer, he sports round sunglasses and a rumpled, dark leather jacket. ‘He was the saxophone player,’ Gabi says. ‘And he didn’t know how to play.’ Fondly, she describes how he would blow his horn, his head growing pro-gressively more red throughout the performance. Unassuming at first glance, studded to Hans-Jörg Mayer’s jacket are two small pins handmade by Gabi: a bundle of keys and a silver skull (1985). I lean in closer to the photograph and note that the skull contains a little, devilish grin. Its smile re-minds me of one of Gabi’s more recent pieces, a white-gold cufflink from 2018 which displays an expressive yet tearful face.

As a teenager, Gabi sent a heartfelt letter to Keith Richards. ‘Your earlier music was far bet-ter’, she complained. Like most artists, Gabi is both maker and critic. Years ago, Gabi pulled all of the stereo cables from the wall sockets at the Munich club Why Not, bringing the music to a sud-den halt. (The venue banned her for six months.)‘The music was probably bad,’ she explains. At the exhibitions of friends, Gabi has given the gift of honest feedback, something not always well received. Her fearlessness, however, has undoubtably contributed to her artistic successes. During her studies, Jünger once suggested that she should consider a career in sculpture, and a newspaper review of Die Schlüssel described her as the worst singer in Germany. (At the time, she was dis-traught.) Ever confident in her interests, these moments have strengthened Gabi’s resolve.

In the past, I have been moved by the careless, confident vigor with which jewelers handle their work and attach it to the body. Each time I witness the laissez-faire, violent stabbing of metal through clothing, I feel a fresh jolt of surprise. As we discuss her work, Gabi handles her pieces this way, casually yet energetically piercing the fine material of her blouse. Demonstrating a three-piece brooch (1981) for me, she arranges its component parts on her chest. By the end of our con-versation, her blouse holds several holes. I remark upon this, and Gabi tells me that years ago, someone once pointed out to her that her shirt was stained. ‘In response, I just cut the stain out of my shirt with scissors.’ Gabi tells me. “‘You see?,” I told them. “Now the stain is gone”.

This conversation was conducted in German, and translations of quotes are mine. You can follow and contact Gabi on Instagram @Dziubajewels. Gabi has a forthcoming 2024 exhibition at the Schmuckmuseum Pforzheim.

About the author:

Nina Moog is a writer and director of photography currently based between Munich and Copenhagen. After a happenstance meeting with curator Kellie Riggs in Rome, she first contributed to Current Obsession magazine as a proof-reader in 2014. Since then, she’s climbed up the CO ladder to become this magazine’s roving Germany correspondent.

Cover Image: 18 piece gold-plated copper brooch, 1979.