We caught up with Tan to delve into her journey, from academia to creating her own space for game-changing conversations and discussions. The interview was composed and conducted by the participants of GEMZ, CO’s very own talent development programme.

CO: Can you tell us more about your journey and how you ended up at Mental Health Arts Space in Berlin?

Kathy-Ann Tan: My journey and transition out of academia into the field of independent curatorial practice and running an arts/project space of my own has been one of the best decisions I have made. Leaving academia has meant that I can now create and hold spaces for conversations and discussions, that I can facilitate sessions where people can practice deep listening and interaction, where knowledge can be transmitted but also shared in different strategies of mutual and self-empowerment, and all this on my own terms and not the behemoth of academia where each person is simply part of a larger system that reproduces the mechanics of structural racism, exclusion and tokenism.

I will speak a bit more about the space I run, Mental Health Arts Space in Berlin, later in this interview. But for now I can say that, as much hard work as it is to create a sustainable space that supports marginalized communities in the arts and cultures, it’s entirely worth it.

For me, curatorial practice is centrally a practice of facilitation, of bringing people together in safer spaces so as to be able to have vulnerable, honest and open conversations that would not normally take place in a more rigid setting like an academic conference. For me, focusing on mental health in the arts was an intuitive direction because this is precisely the one thing that independent artists and cultural workers don’t speak about quite enough, whether it’s because they are embarrassed, because they don’t have the resources or space to do so, or because of how harsh the art world can be in terms of judging you as an artist.

CO: What does adornment or jewellery mean to you personally and how would you want to see the definition being reviewed in the current society?

KAT: I would like to think of contemporary adornment as a means of challenging traditional ideas associated with jewellery – in terms of class, social status, who had access to precious metals and stones, who could afford to wear jewellery and what kind of social standing did that convey to everyone else? Contemporary adornment seeks to make jewellery more accessible to everyone, but also sees adornment and fashion as a form of expression, whether personal or community-based. So I find it interesting how independent jewellery makers are also going back to patterns, designs and traditions of adornment that are culturally and historically significant. We see this, for instance, with Indigenous designers who are redefining traditional accessories and using beadwork and other traditional motifs and patterns to reclaim their sense of identity, but also to expand and diversify ideas of cultural heritage.

So, I think in today’s context, contemporary adornment or jewellery is an interesting genre where there is the opportunity to experiment with form and make a statement around issues of accessibility and privilege, but also to raise awareness around supporting independent designers from underrepresented communities in the field. Adornment and jewellery is a field of arts and decoration that is extremely white, if one looks at the dominant designers and brands on the market today, and yet the question of where these precious metals and stones are sourced, they tend to come from the Global South. So – support your BIPoC designers and creatives whenever you can!

CO: Today, cultural appropriation is a fundamental issue. In your opinion, where is the line between cultural appropriation and the adoration, the inspiration from a culture that is not our own?

KAT: Cultural appropriation vs. cultural appreciation – that’s been a longstanding debate, and I think one that has been unnecessarily overcomplicated. Very simply, if you are benefiting from drawing on and using cultural histories, patterns, styles, knowledge, music, dress, jewellery, etc. that are not your own, and not doing anything to redistribute resources to that community or culture in question, then you are being culturally appropriative. So, a good example of cultural appropriation would be what I call the ‘yoga industrial complex’ in the Western world, where terms like ‘mindfulness’ and ‘wellness’ are appropriated from Buddhist and Hindu practices of yoga, and yet the amount of money generated by this industry is hardly redistributed or rechanneled to the Global South and East where these practices originate. Instead, there are expensive yoga studios, and yoga becomes a lifestyle, not a practice, for the upper-middle class who can afford to buy well-being.

As for cultural appreciation – this is a problematic concept for me because often those forms of ‘appreciation’ involve an exoticisation or orientalising (Edward Said) of the ‘other’. The classic example is when white people are fascinated by Black women’s hair and want to touch it in order to ‘feel’ it for themselves. That form of ‘appreciation’ is violent and reveals the sense of entitlement that the white person has over whom them deem the ‘other’.

To connect this to the question of whether jewellery and contemporary adornment is a field that can contribute to the ongoing discussion and practice of decolonisation of the arts, I think it can definitely differentiate itself from the ubiquitous cultural appropriation in the fashion industry and set examples of how an artistic and creative practice can be sustainable but also demand ethical sourcing and social equity.

CO: How did you start with Mental Health Arts Space Berlin? Do you think this model could exist in another place than Berlin?

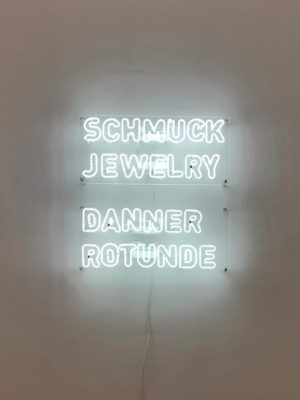

KAT: So I can talk a little bit about my curatorial practice, which, currently, is very much connected to the independent, non-profit arts & project space that I run in Berlin-Charlottenburg, Mental Health Arts Space.

I opened the space in April this year, and since then I have curated events such as a group exhibition on Black memory and histories of resistance, therapy sessions by a Black woman therapist, film-screenings of queer and African films, reading group sessions on intersectional feminism, and even a half-day retreat on heartbreak as practice. This is what I mean by ‘alternative models of art dissemination, exhibition-making, and institution-building that are attuned to issues of social and transformative justice.’

I am not interested in Mental Health Arts Space (further in the article as MHAS -ed.) becoming a large institution. On the contrary – I want it to be a small, cosy and intimate space where people feel they can always drop by and spend some time – to just sit and browse the bookshelf, listen to a podcast or sound recording, access the Internet and browse the websites of Queer artists of colour, have a conversation, grab a coffee or tea, and just dwell. Mental Health is not a luxury. As the Black queer feminist writer, activist and scholar Audre Lorde once said, ‘Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.’ That holds true particularly for marginalised and underrepresented groups in the arts and cultures where there are very few structures in place that care for their mental health and well-being, needless to say for their flourishing and growth in the art world.

The area where MHAS is situated in Berlin-Charlottenburg is interesting because in the 1960s, there was a large community of Turkish migrants that had come to Germany to work in the labor-intensive industries. In the 1980s, these communities left this area, moving to the south of Germany to areas like Stuttgart where the new Porsche and Mercedes-Benz factories required more labor and thus were hiring more migrant workers. So, the area changed from a predominantly white German-speaking area in the early 20th century, to a more diverse population in the 1960s, and then increasingly became whiter again towards the end of the 20th century. The road that the space is on, Kaiserdamm, was also rebuilt in 1939 as part of the East-West Axis of the planned Welthauptstadt Germania, which was Hitler’s vision for the future of Berlin during the Nazi period. I thus also see it as an important and symbolic act of reclaiming this space, to center BIPoC, queer and minoritized voices in this space that, not that long ago, was an exemplary site of white supremacy.

‘Surround yourself with supportive communities and engage in practices of collective care. Challenge and question existing systems and narratives, and remember that your voice and perspective are valid and valuable.’

CO: Why do you think the body is an important tool to challenge neo-colonial structures? And what advice would you give to BIPoC artists in the Western art scene who feel uncomfortable there?

KAT: This is why I believe that one’s curatorial practice should be rooted in their bodily experience, as all bodies are unique and should not be homogenised. It is important to connect with one’s histories and cultural ancestry, especially for post-migrant generations who were born in Europe but whose parents were not. I am sceptical of federal programs that emphasise ‘integration’ (so please do not talk to me about ‘Integrationspolitik’!) because I believe that this is a personal and intimate experience that cannot be dictated by government initiatives that outline what it means to be a ‘good’ and ‘integrated’ German. To feel connected and embedded in the larger community, one needs to be patient and allow their roots to grow, with the support of practices of collective care and exchange. Un-learning our colonised systems of knowledge, value, and work is also central to this process. This is why the arts have the potential to challenge these systems and binaries, as it fosters and is fostered by imagination. Institutions such as museums and state-run art galleries need to keep this imagination alive, while also being accountable for their origins and histories of establishment, which often were part of the larger colonial project of displaying hegemonic rule.

My own curatorial practice is centered around a decolonial practice of collective care and support. Art is not only of ‘systemic importance’ (‘systemrelevant’) to me, but it is also crucial in fostering a sense of identity, belonging, community, and critical voice in our societies, as I have written elsewhere. Another curatorial project of mine is DecolonialArtArchives (www.decolonialartarchives.com), an online and offline platform that aims to collaboratively build a forum for artists, curators, and cultural workers to interrogate colonial narratives in the arts and cultures and beyond. It is based in Berlin but reaches beyond the bubble of Berlin’s art and cultural scenes to connect with the works, projects, life experiences, and knowledge archives of those who are working hard around the world to dismantle the structures of white supremacy and extractive racial capitalism.

As for advice to BIPoC artists in the Western art scene who feel uncomfortable, I would say to trust your own bodily experience and self-positioning. Connect with your histories and cultural ancestry, and don’t feel pressured to conform to external expectations of what it means to be ‘integrated’ or accepted. Surround yourself with supportive communities and engage in practices of collective care. Challenge and question existing systems and narratives, and remember that your voice and perspective are valid and valuable. Keep nurturing your imagination and creativity, and continue to make art that speaks to your truths and experiences. You are not alone, and your presence and contributions are important in reshaping the art world and challenging neo-colonial structures.

This interview was edited for clarity.